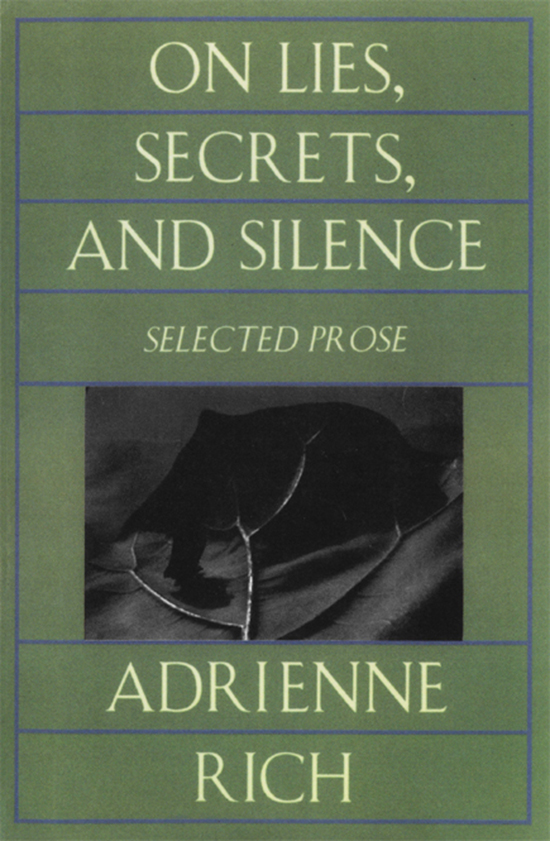

On Lies, Secrets,

and Silence

Selected Prose 19661978

ADRIENNE RICH

ADRIENNE RICH

W W NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

Copyright 1979 by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

First published as a Norton paperback 1980; reissued 1995

All rights reserved

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Rich, Adrienne.

On lies, secrets, and silence.

Includes bibliographical references.

l.Title.

PS3535.123306 814'5'4 78-26432

ISBN 978-0-393-31285-0

ISBN: 978-0-393-34811-8 (ebook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London WIT 3QT

In October 1902, Elizabeth Cady Stanton died at the age of eighty-seven. Susan B. Anthony had worked with her for fifty years. Together, they had learned the meaning of activism in the abolitionist movement. Together, over the cradles of Stantons seven children, they had hammered out political strategy and speeches; together they had traveled from town to town organizing suffrage meetings; together had faced abuse and indignation, caricature and slander; together had argued, disagreed, and persevered through the bonds of an unremitting love and loyalty. Anthony, bereaved both of her most intimate friend and her most trusted colleague, found herself on Stantons death beset by reporters, whose questions revealed how little they knew and understood of the movement she and Stan-ton had labored in for half a century. Her cry of impatience could strike a chord of recognition in radical feminists today: How shall we ever make the world intelligent on our movement?

As I write this, in North America 1978, the struggle to constitutionalize the equal rights of women finds itself facing many of the same opponents that the fight for the ballot confronted: powerful industrial interests, desiring to keep a cheap labor pool of women or threatened by womens economic independence; the networks of communication which draw advertising revenue from those interests; the erasure of womens political and historic past which makes each new generation of feminists appear as an abnormal excrescence on the face of time; trivialization of the issue itself, sometimes even by its advocates when they fail to connect it with the deeper issues on which twentieth-century women are engaged in our particular moment of feminist history. Susan B. Anthony understood that the demand for the ballot was a radical demand, not simply because she hoped that women voters would use their votes to change the lives of women, but because she sensed a profound symbolism embodied in the denial of suffrage to women: the same kind of symbolism which, in the history of American racism, has surrounded the concept of separate-but-equal toilets, drinking fountains, and schools, the symbolism which pervades any arrangement made by a dominant group for the less powerful or the powerless. Anthony has often been represented as a single-minded, obsessed, narrow-visioned fanatic who could see nothing but the ballot and whose strength was a fanatics tireless drive. We have only to read her published letters, papers, and speeches, to recognize that she was a remarkable political philosopher, who deeply loved and was loved by women and drew on that love for her strength and persistence; who understood how both middle-class marriage and factory labor enslaved women; who comprehended to the full, and never compromised upon, the radical symbolism of the constitutional amendment for which she and Stanton fought for a lifetime, and whose ratification neither lived to see.

But most twentieth-century feminists have not read the lives and works of Anthony and Stanton, except perhaps as excerpted in anthologies. The six volumes of the History of Woman Suffrage and Ida Husted Harpers three-volume life of Anthony, both densely packed sources of knowledge about the real thought and feelings of nineteenth-century feminism, exist in library reprint editions; only Stan-tons autobiography has been reprinted in paperback.

The entire history of womens struggle for self-determination has been muffled in silence over and over. One serious cultural obstacle encountered by any feminist writer is that each feminist work has tended to be received as if it emerged from nowhere; as if each of us had lived, thought, and worked without any historical past or contextual present This is one of the ways in which womens work and thinking has been made to seem sporadic, errant, orphaned of any tradition of its own.

In fact, we do have a long feminist tradition, both oral and written, a tradition which has built on itself over and over, recovering essential elements even when those have been strangled or wiped out. Yet still a Mary Wollstonecraft (labeled the hyena in petticoats) is viewed without reference to her forebears, not only the sixteenth-century women pamphleteers but the wisewomen and witches, who had been the objects of wholesale persecution and massacre for three centuries. So also Simone de Beauvoir has been read without reference to the destruction of the political womens clubs of the French Revolution, or the writings of Olympe des Gouges and Flora Tristan. So also has the articulate political feminism and socialism of Virginia Woolf been obscured by the notion that she was Blooms-buryindividualist, elitist, lacking class-consciousness, and gay in the most frivolous sense, without reference to her connections with Margaret Llewelyn Davies, the Womens Cooperative Guild, the antipatriarchal anthropologist Jane Harrison, the lesbian/feminist So also is each contemporary feminist theorist attacked or dismissed ad feminam, as if her politics were simply an outburst of personal bitterness or rage.

In particular, the womens movement of the late twentieth century is evolving in the face of a culture of manipulated passivity (the mirror-image of which is violence, both random and institutional). The television screen purveys everywhere its loaded messages; but even when and where the message may seem less deadly to the mind, the nature of the medium itself breeds passivity, docility, flickering concentration. The decline in adult literacy means not merely a decline in the capacity to read and write, but a decline in the impulse to puzzle out, brood upon, look up in the dictionary, mutter over, argue about, turn inside-out in verbal euphoria, the incomparable medium of languageTillie Olsens term. And this decline comes, ironically, at a moment in history when women, the majority of the worlds people, have become most aware of our need for real literacy, for our own history, most searchingly aware of the lies and distortions of the culture men have devised, when we are finally prepared to take on the most complex, subtle, and drastic revaluation ever attempted of the condition of the species.

The television screen has throughout the world replaced, or is fast replacing: oral poetry; old wives tales; childrens story-acting games and verbal lore; lullabies; playing the sevens; political argument; the reading of books too difficult for the reader, yet somehow read; tales of when-I-was-your-age told by parents and grandparents to children, linking them to their own past; singing in parts; memorization of poetry; the oral transmitting of skills and remedies; reading aloud; recitation; both community and solitude. People grow up who

Next page