S imply put, a genogram is a map of who you belong to. For those of us who think systemically, genograms are the basic grounding map for therapy. A genogram offers the clinician a basic picture of who clients are, where they come from, and who matters in their lives. It offers a framework for understanding the present stresses, the past struggles, and the resources that will be available to you and your clients during therapy. Genogram mapping is an essential organizing tool to help clinicians understand clients and to help clients understand their problems and their lives. Without this kind of mapping, it is almost impossible to keep track of our clients lives or to help them see the patterns in which they are embedded.

Genograms map the connections to the biological and legal kinship network as well as to the informal network of friends, pets, and work connections in a persons life. This map, along with a time line or family chronology, provides an essential guide for holding the complexity of a persons experiences, characteristics, values, network, and context in mind in assessment and therapy.

Genograms also map the evolution of a persons relationships, indicating who was important in the past and what earlier patterns may be repeating themselves currently. They track the persons and the familys history, although we generally make a separate time line of the genogram information to make the relevant chronology more explicit.

Genograms also help us attend to clients ways of belonging in the world, which are essential to healing. Our clinical job entails reminding clients of who they belong to as a way of helping them recognize their strengths. So often when people are in trouble, they feel isolated, forgetting this rich context of belonging. But everyone has a rich context, even those who feel currently alone. As Paolo Freire (1994) put it in The Pedagogy of Hope:

No one goes anywhere alone,... not even those who arrive physically alone, unaccompanied by family, spouse, children, parents, or siblings. No one leaves his or her world without having been transfixed by its roots, or with a vacuum for a soul. We carry with us the memory of many fabrics, a self soaked in our history, our culture; a memory, sometimes scattered, sometimes sharp and clear, of the streets of our childhood, of our adolescence, the reminiscence of something distant that suddenly stands out before us, in us, a shy gesture, an open hand, a smile... a simple sentence possibly now forgotten by the one who said it. (p. 31)

Murray Bowen used to say that the ideal of mature relating (what he referred to as differentiation) is to have a person-to-person relationship with everyone in your family. If we start with the most basic aim of therapy from a systems perspective, we might say it is to help clients make the best choices for their lives. And in order to make the best choices we human beings need to appreciate that we are all connected to each other and to the earth, to the past and to the future of each other and of our planet. So making the best choices means aiming toward positive connectedness with family, friends, community, coworkers, and nature that surround us. The aim of therapy is to support clients maximal self-effectiveness in their lives.

Assessment, engagement, and the work of therapy are always aimed at helping clients find the best ways to manage their troubles and relationships. Genograms are a primary orientation tool for helping clients figure out where they have become stuck and where their best resources reside. As we learn about clients lives in context, we can support them in figuring out which relationships they want to modify and how we can help them gather their strength for these efforts.

Before people can make the best possible choices for their lives, they must first be centered and able to think clearly where they are and what their connections mean to them. Without that centeredness, it is impossible to figure out where they want to be going in their lives and relationships. Assisting clients to view themselves in the context of their genograms is aimed at helping them figure out how to live in respectful relationships with others and with nature, to care for and be cared for by others as appropriate, and without exploitation or disregard for our world or for future generations.

This aim requires clients developing a solid sense of their cultural, spiritual, and psychological identity in the context of their connections to others. This requires appreciating that our lives are always a part of something greater than ourselves. It means, in effect, realizing that we are, to paraphrase Jorge Luis Borges (1972), the embodied continuance of those who did not live into our time. And others will be and are our immortality on this earth (Borges, 1972, p. 21).

The awareness that one is a part of what has come before and what will come after seems crucial for peoples decision making about how to live their lives. Thus it is central in therapy, which is always a matter of ethics and existential choices for oneself.

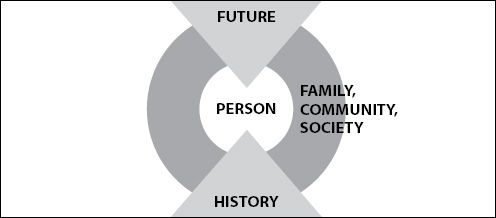

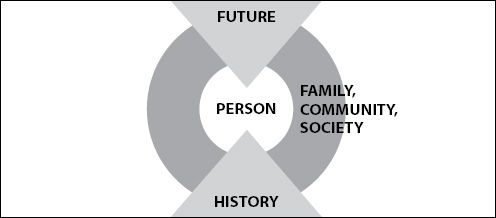

The context for understanding people (see Figure 1.1), that is, the context of our belonging throughout our lives, includes the present context of our family and community, within the longitudinal context of our history, our present, and our future. It carries us all from birth and childhood through adulthood to death and defines our legacy for the next generation. Thinking about ourselves contextually is profoundly important for the problem solving that therapy offers.

Unless we take this context into account, we cannot understand what is really happening. It would be like listening to a single moment in music with no awareness of what came before or anticipation of the implications for what will follow. Without an appreciation of time, musical notes would have no meaning. We human beings are the same. Our lives are always on a path from the past and into the future and they are always connected to others in all these contexts.

Figure 1.1: Context for Understanding People

Genograms help us focus with our clients on their context as they moves through time aware of the others to whom they are accountable and from whom they have derived their resilience. Genograms name the names of those people who are and have been in a clients life and those who have come before.

When people come for therapy they have often lost their bearings, their sense of themselves in time, space, and relational context. Most of the time people seek help because of some problem in how they are feeling (anxiety, depression) or a problem in their relationships with other family members or within their community. This may have been brought on by a lossan illness; a death; the threatened loss of a relationship, a job, their childs functioning; or the loss of another family member. Often they feel let down by others or anger or resentment at others for not appreciating them. They feel they have been treated unfairly by others or by life. They may have a sense of Why me? or Why should I have to be the one to take responsibility? Or they feel inadequate to live up to a legacy that has been passed down to them. They have often become trapped in viewing themselves as victims of their own lives or family. Clients frequently come to therapy complaining about someone else, but at the end of the day, the only one they can really change is themselves. As Irving Yalom puts it in

Next page