THE GIRLS

SAPPHO GOES TO HOLLYWOOD

DIANA MCLELLAN

Booktrope Editions

Seattle WA 2013

Copyright 2013 Diana McLellan

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License .

Attribution You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work) .

Noncommercial You may not use this work for commercial purposes .

No Derivative Works You may not alter , transform , or build upon this work .

Inquiries about additional permissions should be directed to: info@booktrope.com

Cover Design by Victoria Wolffe

Edited by Rebecca Howland

PRINT ISBN 978-1-935961-54-3

EPUB ISBN 978-1-62015-058-0

For further information regarding permissions, please contact info@booktrope.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013944321

Table of Contents

I believe absolutely that the reader cannot understand the character and deeds of the subject unless he is given a basic understanding of that person's sexual loves and hates and conflicts. It is the only way [to] make sense of apparently senseless actions.

LOUISE BROOKS

THE EXCITING SECRETS

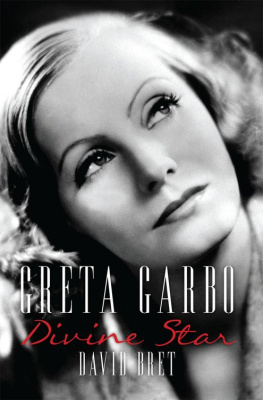

GRETA GARBO CALLED HOMOSEXUAL AFFAIRS "exciting secrets."

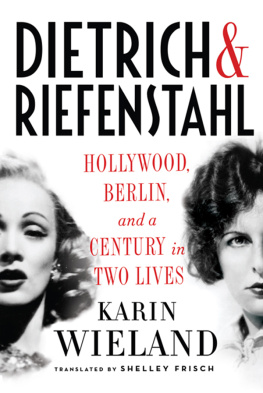

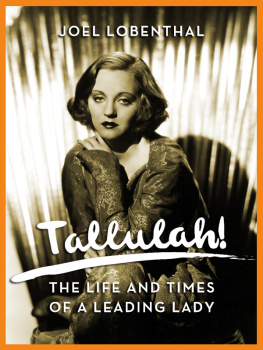

And if you were "one of the girls," as early Hollywood described Sapphic stars ranging from the great Nazimova to Marlene Dietrich, Tallulah Bankhead, and Garbo herself, exciting secrets lent both your life and your art its edge. Lesbian affairs, it was widely felt, were good for you. They expanded your emotional range, nurtured your amour propre, kept your skin clear and your eyes bright, burnished your acting skills, and evenas director Josef von Sternberg believedexerted a powerful androgynous magnetism through the camera's lens, attracting the unwitting desires of both men and women in the audience through the dim, smoky air of the movie house.

Secrecy, of course, was key. In that unenlightened age, secrecy about affairs placated bluenoses, deflected jealousies, and protected reputations, as well as adding its own thrill. But secrecy meant lies. And when I began my long trek into the Sapphic Hollywood of the first half of this century, hoping to unveil a history long buried beneath the Victorianism "the girls" so boldly defied, I quickly discovered that lies their liesblocked my path at every turn.

Luckily, I had met lies before. And as a Washington journalist for thirty yearsten of them spent as a daily gossip columnist who received far more sensational information, true and false, than I could ever printI had made a useful discovery: One big, proven lie reveals far more than dozens of widely reported "truths" once you understand why it was told. This rule, in my experience, applies to politics, sex, war, diplomacy, White House scandals, social invitations, funeral orations, almost everything in Washington.

Would it apply to Hollywood, too? I believed it would.

And so, over the five years I devoted to this book, I turned armchair detective. Whenever I could document a consistent unnecessary lie, I fished more intently in the waters around it than elsewhere, hooking in as many sources as possible, arranging events in the correct sequence to determine cause and effect, applying what I knew to areas I did not know, and slowly triangulating my way toward the truth. My hope was not to "out" my girlsof whom I became very fondbut to understand their minds, their lives, and the times and contexts in which they livedsocial, sexual, theatrical, political, and even cinematic. Soon little gold nuggets began to glimmer at me from between the lines of letters, published and unpublished; they lurked embedded in thousands of pages of long-secret government documents that, after realizing their importance for my purposes, I slowly acquired. Occasionally, as my understanding grew, they jumped out of otherwise-predictable newspaper and magazine articles, and from films and photographs dating back more than ninety years.

Watching the wall of lies begin to crumble was an adventure as exciting for me as the opening of a pharaoh's tomb. Through the rubble, I glimpsed a never-before-reported affair between Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich (who lied for the rest of their lives, saying that they had never met). I found a hitherto-untracked husband-cum-consort of Dietrich (who lied about his existence)and swirling about him, and the girls, I found some long-lied-about Hollywood skullduggery, which ultimately led to the Hollywood Ten trials of suspected Communists halfway through the century.

How did my system work? Let's take the Garbo-Dietrich affair, which I explore in Part 2. In my view, it was the turning point in Greta Garbo's life. Much of what defined the mysterious starher obsession with privacy and secrecy, the bizarre rules she set up for those allowed to peep into her temple of solitude, even the premature ending of her film careersprang from her reaction to this pivotal event, which occurred when she was nineteen.

When I began, like all biographers of those two superstars of the twenties, thirties, and forties, I subscribed to the conventional wisdom, emphasized so often by both Garbo and Dietrich: The two women had never met. Hollywood buffs usually cite the wonderful story of their "introduction" in 1945 by Orson Welles (see the "Marlene Wins the War" section in Chapter 53).

But their lifelong claim to be strangers was a lie. This reality struck home as I sat alone one day in a tiny film booth at the Library of Congress's Motion Picture Division, with Garbo's 1925 silent film The Joyless Street (Die freudlose Gasse) humming through the track before me. Suddenly, my heart jumped. I stiffened. I stopped the film, then rolled it back. I rolled it again, and again, and again. Over the past several months, I had examined, very closely, scores of photographs of Marlene in Berlin and Vienna in the 1920s. For much of that time, she dyed her hair black for roles in cabarets, onstage, and in films. (She found black-haired women sexier than blondes. She also painted her brows black, shadowed her eyes, and rouged her lips into a Cupid's bow.) With no distinctively Dietrich voice, no blond hair, and without the face-modeling lighting techniques she would learn five years later from von Sternberg, she would not be recognizable to most fans in this small but by no means insignificant roleparticularly if she swore she wasn't in the film. (I might not have recognized her myself, had not four years of youthful art training taught me how light molds form.) I sat there for hours. I stopped the film often, ran it back, watched over and over wherever Dietrich appeared. I compared every feature of the face, the makeup, the hair, the legs, the hands and arms with the Marlene I knew from her early photographs. I looked for the gestures Marlene made in later films. And there they werethe brushing aside of a stray lock of hair, the characteristic spread of her most unusual hands, with their long, meaty, muscular palms and short, tapered violinist's fingers, the lift of her shoulders, the defiant puff of her cigarette smoke. Even though the Garbo film I was watching had been censored, edited, plundered by unprincipled researchers, and otherwise cut to shreds over the years, there was no question at all in my mind that the woman I was watching in several key scenes, unbilled in the credits, was Marlene Dietrich. I called in the film librarian, Madeline Matz. At first she was incredulous. And then she agreed: Yes, I was right. That was Marlene, with her mouth open, caught in close-up on my little silver screen. So, to paraphrase the husband caught by his wife in bed with his secretary, who are you going to believe? Marlene and Greta, or your lying eyes? Examine the photographs of Marlene and the stills from The Joyless Street I have presented, then judge for yourself.