About Island Press

Since 1984, the nonprofit organization Island Press has been stimulating, shaping, and communicating ideas that are essential for solving environmental problems worldwide. With more than 1,000 titles in print and some 30 new releases each year, we are the nations leading publisher on environmental issues. We identify innovative thinkers and emerging trends in the environmental field. We work with world-renowned experts and authors to develop cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental challenges.

Island Press designs and executes educational campaigns in conjunction with our authors to communicate their critical messages in print, in person, and online using the latest technologies, innovative programs, and the media. Our goal is to reach targeted audiencesscientists, policymakers, environmental advocates, urban planners, the media, and concerned citizenswith information that can be used to create the framework for long-term ecological health and human well-being.

Island Press gratefully acknowledges major support of our work by The Agua Fund, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Bobolink Foundation, The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, Forrest C. and Frances H. Lattner Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The Oram Foundation, Inc., The Overbrook Foundation, The S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, The Summit Charitable Foundation, Inc., and many other generous supporters.

The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters.

Copyright 2016 Alexander Garvin

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036

Island Press is a trademark of The Center for Resource Economics.

Keywords: beach, Bilbao, boulevard, business improvement district (BID), habitability, livability, park, pedestrian, plaza, promenade, public realm, public square, public transit, rectilinear grid, remediation, resilience, street, urbanization, walkability

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015960067

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Chicago lakeshore (2008). (Alexander Garvin)

PREFACE

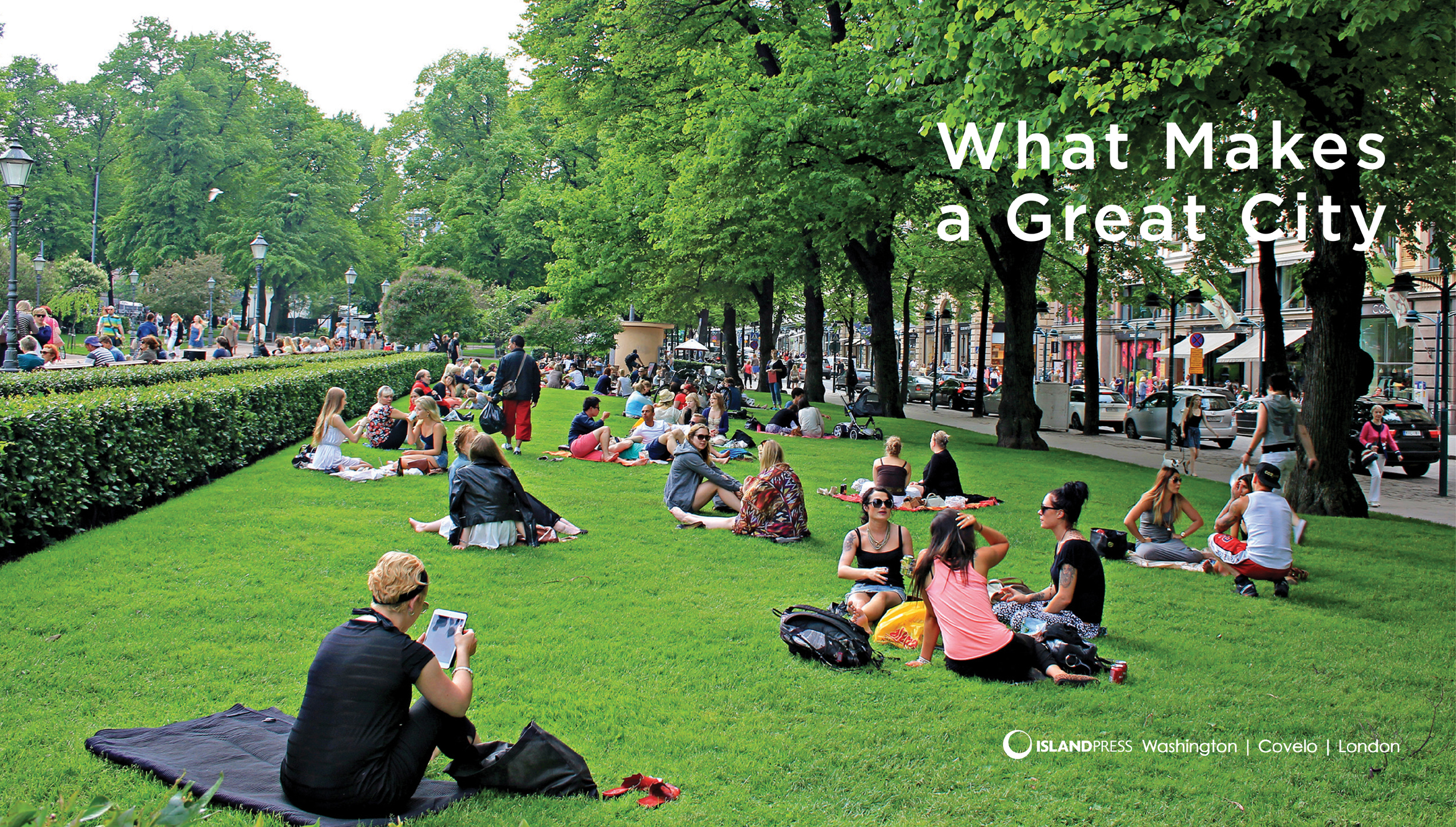

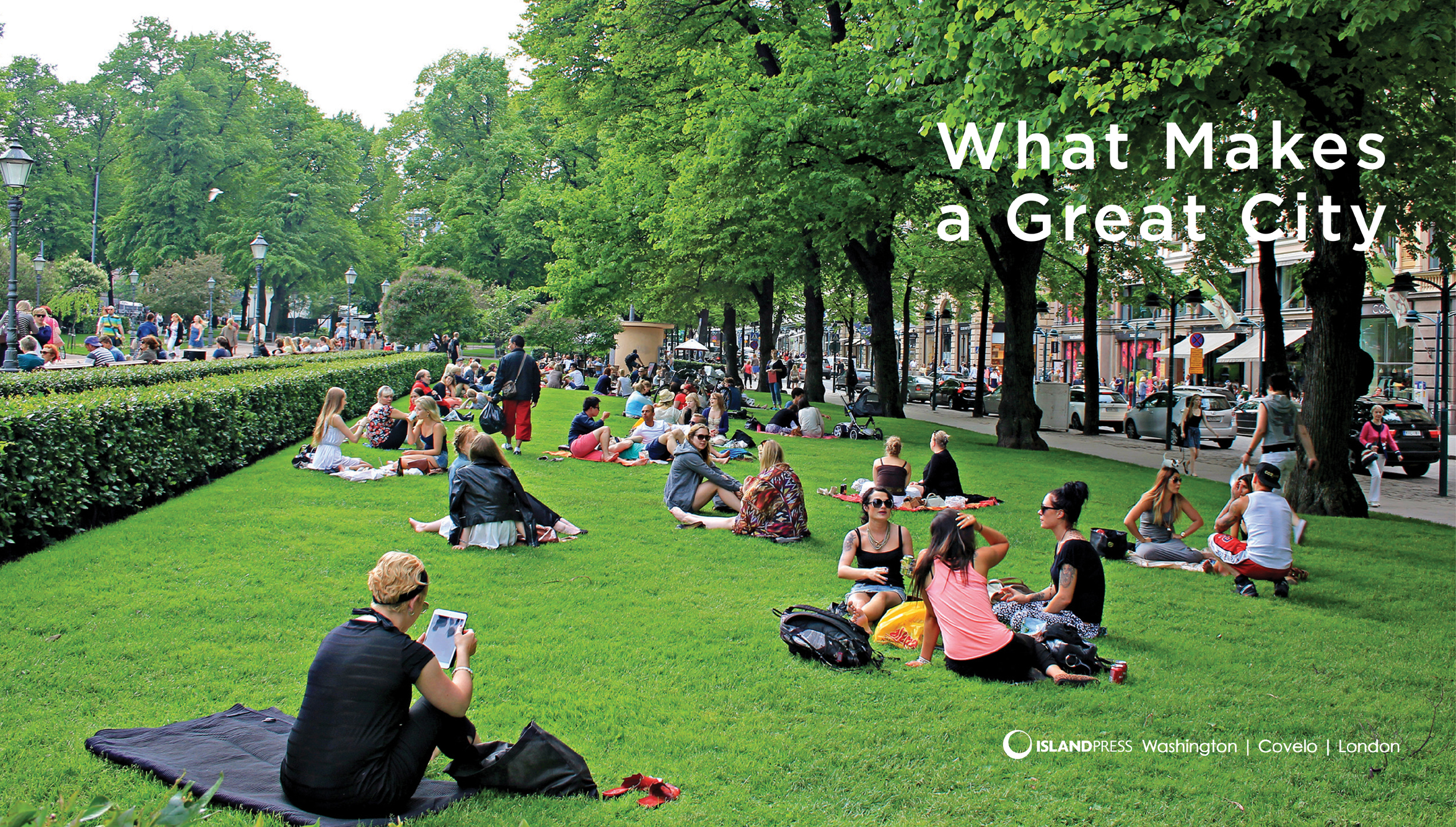

What Makes a Great City

A few years ago a friend asked me, What makes a great city? Despite having studied cities for more than half a century, I had no ready answer to this question. All that evening I found myself coming back to it: What makes a great city? Not a good city, or a functional city, but a great city. A city that other cities inhabitants feel obliged to admire, emulate, and learn from. I thought about the Chicago lakeshore, with thousands of people on the beach enjoying the sun in front of a backdrop of stupendous office towers and apartment buildings. I remembered the first time I strolled down the Champs Elyses in Paris. I even reread a passage from F. Scott Fitzgeralds essay My Lost City, in which he described the skyline of Manhattan as the white glacier of lower New York swooping down like a strand of a bridge to rise into uptown. No matter how I tried, I was still unable to answer the question.

I thought about the reasons people come to a city in the first place. The reasons are as numerous as the residents of the city. They come for work, for intellectual stimulation, to do business, to shop or sightsee, and sometimes even to start a new life. They come to visit a department store, attend a college, sample a hotel, consult a library, be treated in a hospital, browse a museum, see a show, or visit one of the thousands of other useful and interesting destinations that all great cities provide. Yet, whether people come to a city for a day or to live there permanently, a city must do more than contain the stores, schools, libraries, museums, residences, places of employment, and other facilities for them to use, either alone or with others.

A great city also must be easily accessible, safe, and friendly. It also must include a wide array of well-maintained amenities that are open to anyone and provide something for everybody. And, most important, it must offer people a chance to achieve their dreams. These were certainly characteristics of a great city. They did not, however, answer the question, What makes a great city?

As a professor of urban planning and management at Yale University, for most of my adult life I have been observing and writing about the major municipal centers of the world. And yet, that night, and the next day, and the day after that, I simply could not come up with a satisfactory answer to my friends seemingly simple query. This fact bothered mea lot.

So, gradually, an idea began to take root in my mind: Why not take advantage of the time and opportunities that come my way during the next year or so to travel to some great cities to answer this important yet elusive question? I had already traveled to most countries in Europe and to all the major cities of the United States, but never with the intent of answering this particular question. With the question in mind, Id make a special visit to Paris, which I knew well from working there as a young architect and which I believed had for centuries set the standard for a brilliantly designed and managed urban realm. Id go back to American cities that were thought to be examples of good planning, such as Portland, Oregon, and Minneapolis, and cities, such as Houston and Atlanta, that many experts criticized as examples of terrible planning. Id spend time in Madrid, which in the past few years has bootstrapped itself up from urban anarchy to one of the most well-run cities in Europe. Id even revisit places in New York City, which has always been my home and where I had worked in different capacities within five different city administrations.

I decided that I would not go to cities outside North America and Europe for three reasons. First, I have a rule that I have followed for nearly half a century: I neither speak about nor write about places to which I have not been. Second, I would not have the time I needed to learn about the many cultures of Africa, the Middle East, or South Asia. And third, although I had been to some cities in East Asia, as well as to Turkey, Australia, and South America, I had only a superficial understanding of their centuries-old cultures, and I knew better than to try to develop the deep understanding that would be required to write knowingly about cities that I did not know well.

In all, I planned to visit the cities in Europe and North America that my respected colleagues and I considered among the great cities of the world and some that experts thought illustrated mediocrity or worse. Once there, Id observe them close-up. Id wander their streets, browse their shops and museums, eat at their sidewalk cafs, study their traffic patterns and pedestrian zones, sit in their parks, cycle their bike lanes, talk to their people, and breathe their air, and in the process keep posing the question, What makes this city so special? What makes a great city?

Next page

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper

Printed on recycled, acid-free paper