The total of Russian losses vary, with reliable modern estimates claiming between 21,000 and 25,000 killed, wounded and captured, and about 5,600 stragglers later re-joining the army. The estimates for Austrian dead and wounded are approximately 4,200, or about 1214 per cent of the forces engaged a similar proportion to French losses. Again, stragglers returning to the ranks should be taken into account, leaving estimated total Allied losses at perhaps 20,00025,000 men, of whom, according to official French records, almost 9,800 Russians and nearly 1,700 Austrians fell captive. French casualties amounted to approximately 9,00010,000 killed, wounded or captured. Whatever the precise figures, this represented a small proportion of those engaged, considering the extent of the success achieved.

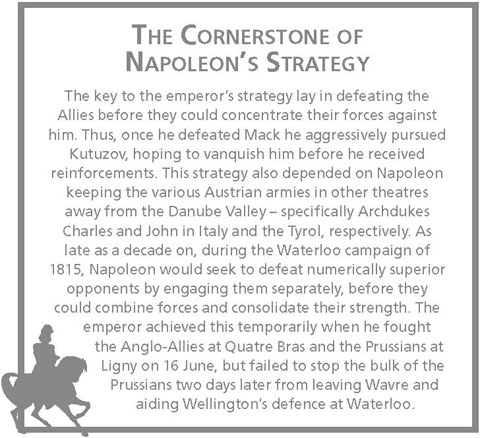

Emperor Francis arranged a meeting with Napoleon in the early hours of 3 December and offered an interview to discuss general peace. This confirmed that Napoleon had not simply defeated Austria; he had dismantled the Third Coalition by knocking the Habsburgs altogether out of the war. The two sovereigns met again, near Austerlitz, on the 4th, with Napoleon initially hopeful of pursuing the remnants of the Allied army so as to inflict the greatest possible damage on the Russians before an armistice could take effect. In fact, although sufficient French troops stood ready for pursuit, they had largely lost contact with Russian forces, which had begun their withdrawal towards Hungary. In the event, despite a limited French effort at pursuit on the 3rd, the Russians had made good their escape. Thus, with the Austrians left to fend for themselves, Napoleon and Francis agreed terms of an armistice to which the tsar pledged to adhere.

Having arranged for the cessation of hostilities, Napoleon returned to Vienna and briefly met the Prussian ambassador, Count Haugwitz, on 7 December. Haugwitz had always advocated peace and believed that the radically changed circumstances justified his withholding the kings Potsdam ultimatum, meant to be delivered to the French emperor, outlining the threat of Prussian intervention in the campaign. Instead, in a humiliating turn of events, Haugwitz congratulated Napoleon on his success and awaited the consequences of the campaign for his still powerful, yet now isolated, country. The emperor thereafter spent the next several weeks with Talleyrand working out the details of the peace treaty to be presented to Austria, and also considered his policy towards Prussia. He intended to deal harshly with the former and to penalise the latter for her failure to remain genuinely neutral during the campaign.

Concluded on 26 December 1805, the terms of the Treaty of Pressburg, signed in what is now Bratislava, were nothing if not harsh, starting with a war indemnity of 40 million gold francs (c. 2 million in 1805) imposed on the Habsburgs, together with demands for large territorial cessions in Italy and Germany. In the former, Pressburg reaffirmed the extensive French territorial gains achieved there as a result of the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797 notably Venetia, Dalmatia and Istria, territories whose cession the settlement at Lunville confirmed in 1801 and obliged Austria to recognise Napoleons more recent inroads in Italy, including the annexation of Genoa and his adoption of the title of King of Italy. The treaty also stipulated that Venetia became formally annexed to the French Empire.

Discussing peace at Schnbrunn Palace, near Vienna, where French and Austrian officials hammered out some of the terms which broke up the Third Coalition. Most of the talks took place at Pressburg (now Bratislava), which lent its name to the treaty.

In Germany, Austria was forced to cede its scattered holdings to Napoleons three recently acquired south German allies: Bavaria, Wrttemberg and Baden. The first of these, for her loyalty during the campaign, acquired various territories to add to the already substantial Wittlesbach domains: the Margravate of Burgau, the Principality of Eichstadt, the Tyrol, Vorarlburg, Hohenems, Knigsegg-Rothenfels, Tettnang, Argen and the city of Lindau. In Swabia, Wrttemberg annexed the cities of Ehingen, Munderkingen, Riedlingen, Mengen and Sulgen, as well as the county of Hohenberg, the Landgravate of Nellenbourg and the Prefecture of Altorf. Napoleon also altered the status of Bavaria from an electorate to a kingdom. Similarly, the emperor elevated the Electorate of Baden to a grand duchy, and secured for it various territories in Swabia: part of the Brisgau, the Ortenau, the city of Constance and the commandery of Meinau. By way of minor compensation, France permitted Austria to annex the Archbishopric of Salzburg (removing from power the former Grand Duke of Tuscany who had received Salzburg in 1803, but who now received Wrzburg in compensation from Bavaria), Berchtesgaden and the estates of the Teutonic Order. By these means, the states of southern Germany for the first time enjoyed the benefit of contiguous territories. These major territorial losses in Germany represented the beginning of the process to conclude the following year with the formation of the Confederation of the Rhine, a body Napoleon established as a substitute for the now fatally weakened Holy Roman Empire and of which more will be said later. All told, the Habsburg Empire lost 2.5 million subjects.

The loss of Austria from the coalition influenced the conduct of the flanking attacks to be conducted by Allied forces in Hanover and the joint Anglo-Russian expedition to the Kingdom of Naples. Swedish and Russian troops reached Swedish Pomerania in early October and proceeded towards Hanover, there to be joined in the middle of the month by a British expedition landed by the Royal Navy. News of Austerlitz and later of Pressburg, however, dampened the vigour of commanders, who withdrew their forces, with British troops embarking in February 1806. The Anglo-Russian force intended for operations in southern Italy, meanwhile, arrived late, in early January 1806, and re-embarked a few days later on learning news of Austerlitz, leaving Naples to its fate. The decision of Naples to join the Third Coalition was to cost King Ferdinand IV his mainland possessions, for when the French invaded, the Bourbons could not effectively oppose them, and fled to Sicily under British protection. The authorities left behind concluded an armistice with the French on 4 February 1806 and, on 30 March, Napoleon decreed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, King of Naples. There, as in Belgium, Holland, elsewhere in Italy and in much of Germany, Napoleonic rule led to the introduction of various reforms modelled on their French counterparts, including a centralised administration, new civil and penal codes and the expropriation of Church properties. Occupation, in short, left the entire Italian peninsula under either the direct or indirect control of France.

By insisting upon the signature of a treaty of alliance, Napoleon made the most of his defeat of Austria and Russia by isolating Prussia diplomatically from its more powerful neighbours. First, the emperor obliged the king to dismiss Count Hardenberg, the chief minister, whose anti-French sentiments contributed to the king eventually signing the Treaty of Potsdam a month before Austerlitz. To entice Prussia into friendship or at the very least, neutrality Napoleon offered her Hanover, whose transfer was correctly calculated to alienate Prussia and Britain, with France in return receiving the principalities of Ansbach and Neuchatel, both minor territories not contiguous with Prussia herself but useful as rewards for Bavaria in the case of the former, and as a personal reward to Marshal Berthier in the case of the latter.