The shadow of the eagle

Richard Woodman

For

Gail Pirkis

with many thanks

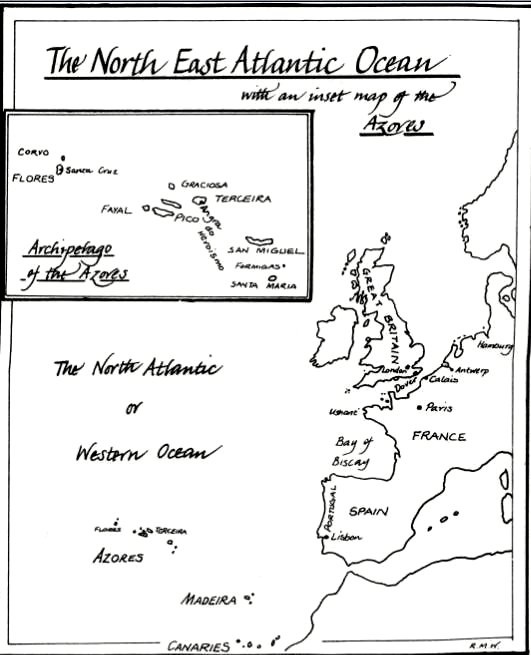

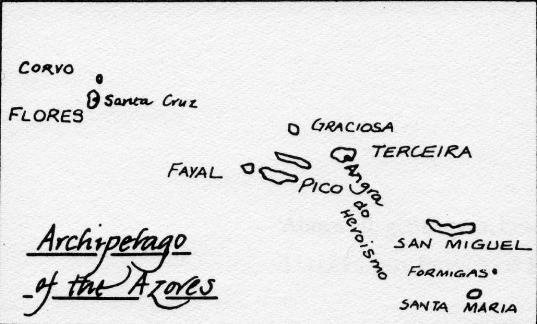

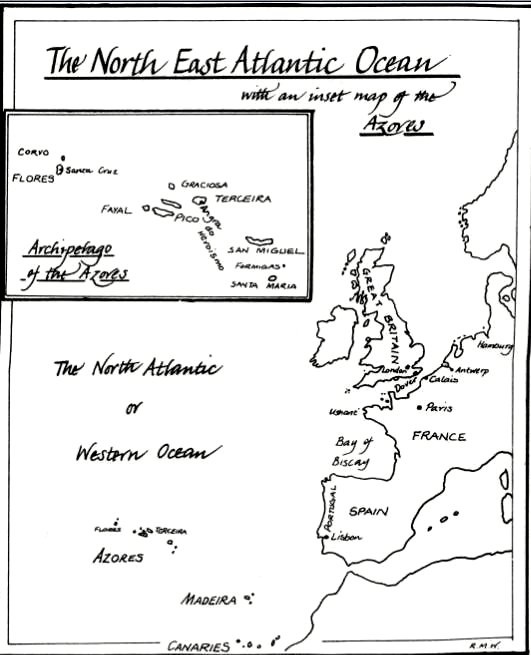

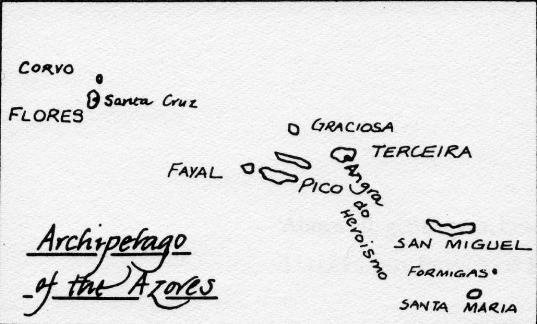

Maps:

PART ONE

A Whisper in the Wind

'Above all, gentlemen, beware of zeal.'

Talleyrand, Prince of Benevento

7 April 1814

'Where in the name of the devil, is Montholon?'

The tall officer, wearing the jack-boots and undress uniform of the Horse Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard turned from the overmantel and addressed the newcomer, a young captain of hussars whose lank hair hung in old-fashioned plaits about his fierce, moustachioed features.

'Delaborde, where the hell have you been?' added a colonel of hussars in the sky-blue overalls and brown tunic of the 2nd Regiment, staring round the wing of a shabby chair in which he was seated, puffing at a long-stemmed clay pipe.

'Where is Montholon?' the horse grenadier repeated.

'Let the poor devil speak.' The fourth occupant of the room commanded. He was dark of feature, his face recessed in the high collar of his plain blue coat, and he had been sitting in the window, quietly reading, while the impatient cavalry officers fussed and fumed.

'Well, Delaborde, you heard what Admiral Lejeune said ...'

'Colonel Montholon sent me to ask you to wait, gentlemen. He apologizes for keeping you all, but he is not yet free to join us.'

'Why not?' asked the horse grenadier.

'He is waiting upon Talleyrand ...'

'That pig ...' A frisson of contempt, mixed with apprehension, seemed to move through the group of officers in the dingy room, enhancing their air of conspiracy.

'It is ironic that it should come to this,' said the colonel of hussars, scratching at the pale weal of a long sabre scar running over the bridge of his nose and down his left cheek. 'Pour yourself a glass Delaborde,' he said, resuming his contemplation of the heavy curls of tobacco smoke that rose from the yellowed bowl of his pipe.

An air of heavy, silent gloom settled on the waiting men, disturbed only by the faint chink of bottle on glass rim and the gurgle of Delaborde's wine. After a few moments Delaborde, prompted by the wine uncoiling in his empty belly, spoke again.

'I am confident Colonel Montholon has the information we want.'

'You mean his sister has the information we want,' sneered the horse grenadier, throwing himself into a spindly chair that stood beside a small, pine table and thrusting out his huge jack-boots so that the rowels of his spurs dug into the meagre square of carpet. The colonel of hussars turned from the wraiths of pipe-smoke and glared at him.

'You may have enjoyed better quarters in the guard, Gaston, but be pleased to respect my landlady's property. This is a palace for a light cavalryman.'

'You aren't thinking of staying,' the horse grenadier remarked sarcastically.

'It looks as though we might have to. Besides it is Paris ... True I had more princely quarters in Moscow, but they were less congenial ...'

'For God's sake where the hell is Montholon?'

'Delaborde has already told you, Gaston. Now hold your tongue, there's a good man.'

Gaston Duroc expelled his breath in a long and contemptuous exhalation. 'I do not like waiting at the behest of a turd in silk stockings...'

'That is no way to refer to the head of the provisional government of France, Gaston,' the colonel of hussars reproved Duroc with a chuckle. 'Talleyrand is not the author of all our misfortunes, merely an agent of destiny. It is we who are going to change that, and if it means waiting until the turd has finished fucking Montholon's sister, then so be it.' Colonel Marbet resumed his pipe.

'Very philosophical, Marbet,' remarked the admiral, looking over his book at Duroc. 'Why don't you join Delaborde in a glass? It seems to have had a good effect upon him.'

They all looked at the young hussar. He had slumped on a carpet-covered chest which stood in a corner of the room, leant his elbow on his shako, and drifted into a doze, the wine glass leaning from his slack fingers.

'Poor devil's hardly had any sleep for a week,' said Marbet, 'he's been escorting Caulaincourt back and forth to Bondy to negotiate with the Tsar. I daresay while Caulaincourt received every courtesy, poor Delaborde was left to sit on his horse.'

Duroc grunted and filled a glass, then the company relapsed again into silence, all of them recalling the tempestuous events of the last few days. Caulaincourt's diplomatic shuttle between the Tsar at the head of the ring of allied armies closing upon Paris, and the beleaguered Emperor of the French at Fontainebleau, had resulted in the allied demand that Napoleon must surrender. A few days earlier, the French senate had cravenly blamed all of France's misfortunes upon the Emperor whom they had formerly fawned upon. Thereafter, Napoleon had abdicated in favour of his young son, but the imperial line was doomed. The British government dug King Louis XVIII out of his comfortable lodgings in Buckinghamshire and prepared to place him on the throne of his fathers. Alone among the crowned heads of Europe who now bayed for the restoration of legitimate monarchy in France, he had never treated with the man they all regarded as a usurper.

To the conspirators in Colonel Marbet's lodgings, the usurper was the elected leader of their country, and the rumours that he had attempted to poison himself gave their intentions a greater urgency.

'Someone's coming!' Duroc's remark galvanized them all. He was on his feet in an instant; Delaborde woke with a start and dropped the glass, caught it on his boot from where it rolled unbroken onto the floor. Colonel Marbet removed the pipe from his mouth and rose slowly, turning in anticipation to the door, while Rear-Admiral Lejeune merely lowered his book.

Colonel Montholon threw open the door and was greeted by the stares of the four men.

'Well?' demanded Duroc.

Montholon closed the door behind him.

'Were you followed?' asked Lejeune.

'I don't think so,' said Montholon.

'Well, where is it to be?' Duroc pressed, fuming with impatience.

'Is the Emperor fit to travel?'

'He'll have to travel, whether he likes it or not,' snarled Duroc. 'The point is where to? You do know, don't you?' The tall man turned on Montholon, 'Or have we got to hang about while your sister ...'

'Hold your tongue, Duroc!' snapped Lejeune, closing his book, standing up and stepping up to Montholon to place a consoling hand upon his shoulder. 'Take no notice of Gaston, Etienne, he's a boor.'

Duroc grunted again and poured another glass. He also filled a second and handed it to Montholon. 'No offence,' he grumbled.

'He's just a big-booted bastard,' Marbet added genially, smiling conciliatorily, his eyes on Montholon. 'Well, Etienne?'

It's to be the Azores, gentlemen,' Montholon said, then raised the glass lo his lips.

There was a sigh of collective relief, then Lejeune, as though finding the news too good, asked Montholon, 'So it is not to be Elba?'

Montholon shook his handsome head. 'No. I am told there has been much debate. The bastards cannot agree ...'

'What of the Tsar?' Lejeune pressed.

'He consents. Absolutely' Montholon replied.

But Lejeune's caution had communicated itself to Duroc. 'He's a damned weathercock. Let us hope he doesn't change his mind.'

Montholon shook his head again. 'No; apparently Talleyrand's stratagem was too seductive.'

'He'd be a damned fool not to consent,' remarked Marbet, 'and your sister had this from Talleyrand himself, eh?'