EROMENOS

Eromenos

Melanie McDonald

Melanie McDonald 2011

www.melaniejmcdonald.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher.

Seriously Good Books

Naples, Florida USA

www.seriouslygoodbooks.net

ISBN: 9780983155409

E-Book ISBN: 978-0-9831554-2-3

Cover and interior design by Ellery Harvey

Cover photo @ 2009 Megan Chapman

www.meganchapman.com

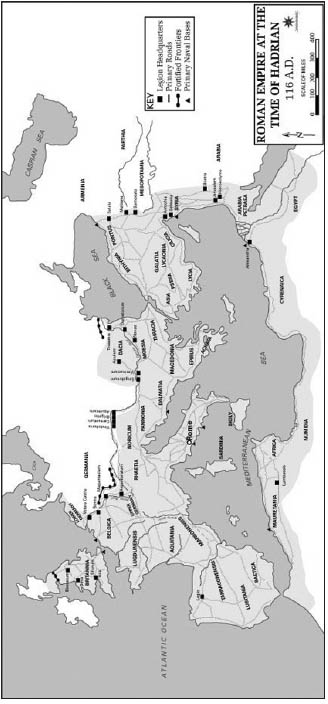

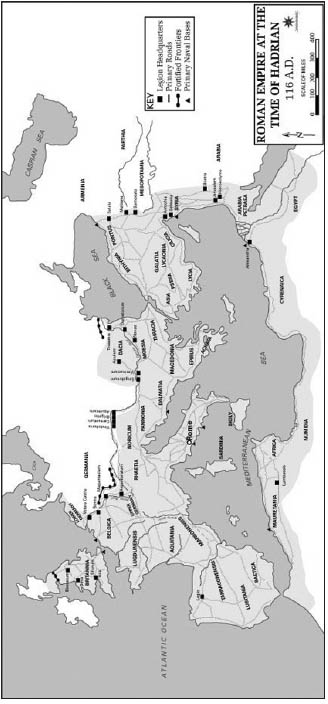

Map courtesy of U.S. Military Academy Archives

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McDonald, Melanie.

Eromenos / Melanie McDonald. 1st ed.

p. cm.

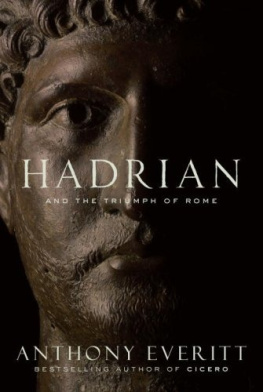

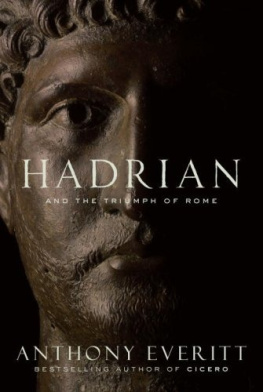

1. Antinous, ca. 110-130Fiction.

2. Hadrian, Emperor of Rome, 76-138Fiction.

3. Favorites, RoyalRomeFiction.

4. EmperorsRomeFiction.

5. RomeHistoryHadrian, 117-138Fiction.

I. Title.

PS3563.A2345E76 2011

8136--dc22

First edition, 2011

EROMENOS

M ELANIE M C D ONALD

S ERIOUSLY G OOD B OOKS

For Kevin

I hate and I love. Why, you might ask.

I dont know. But I feel it happening and I hurt.

Catullus 85

Contents

S UCH A QUIET NIGHT , after Alexandria. I can hear the wild dogs barking along the banks outside Hermopolis, where the imperial fleet lies anchored. Farther down, ibis and river horse alike doze hidden among reeds beneath the turning wheel of constellations. The moon itself is dark, an auspicious sign for my purposes.

Here in our quarters, the only other soul awake is the guard on watch. Should he come round to check, these words are safehe cannot read Greek. These last four nights, while the empire sleeps, I have assigned myself this confession. Any struggle must be resolved here upon these sheets, so the morrow holds nothing but acceptance, acquiescence, peace. With this lamp as witness I record my life until now. When I am finished, I must consign it all, save the final chapter, to the temple fire.

Earth, air, fire, waterall elements must be in accord for Our Lady to accept my offering for Hadrians genius. That confluence of elements approaches.

I WAS BORN in Bithynia, in the town of Claudiopolis, during the reign of Trajan, and named Parthenos Antinous.

I have often wondered why my father and mother chose to name me after the foremost rejected suitor in the story of the Odyssey , killed with an arrow loosed by Odysseus; the shaft pierced his throat, leaving him to gag and choke while the life gushed out of him. Then again, Mantineia in Arcadia, Greek mother-city to our little town, was said to be founded by the princess Antine, guided to its site by a dragon. My name might be descended from hers. Whatever the reason for their choice, my parents carried it away with them into silence. My grandparents must not have known, for they never mentioned it.

My grandfather, Parthenos Philemon, made his fortune through shrewd land negotiations, while retaining the habits and attitude of a small-holdings farmer. He took care to teach me how our Greek forebears invented civilization, government, culture; how the Romans modeled their society on our own, and how our philosophy, medicine, arts and letters remain superior.

From my fathers mother, a tiny, hawk-faced woman, I learned all the old Greek stories, as well as our local beliefs and superstitions. Every mountain, wood and stream belonged to a particular deity, and she claimed the river Sangarius was the birthplace of Dionysos. She said my grandfather was named for a man in ancient times who, alone out of an entire village, offered hospitality to strangers who were gods in disguise. Afterward, that ancient Philemon and his wife saw everyone and everything they loved vanish, destroyed beneath flood waters called forth by the gods, except for their own house, which became a temple.

She also told me how butterflies, those scraps of color that feather the meadows each spring, represent the souls of the departed, a concept known to philosophers as transmigration. Each year I watched when they appeared again, and always chose the most beautiful, a delicate blue, to be my mother.

My mother died in childbed before I turned four, but I remember her: lovely, kind, rather unhappy. Her name was Iris, after the goddess of the rainbow. Im told she was intelligent, for a woman. From her I inherited certain physical characteristics more evocative of Asia than Greece; my broad face, high cheekbones, and deep eyes all disavow the Hellenic purity of my fathers lineage.

As for my father, Parthenos Erythros, a surveyor and veteran of the Dacian wars fought during Trajans reign, he was to be the heir, but his early death diverted the family properties into the care of his younger brother, Thersites. Though my father emphasized the superiority of Greek culture, he also took pride in the engineering feats accomplished by the Roman government. The imperial roads and aqueducts offered a vast improvement in living standards, especially for those in small towns.

My family grazed its herds on a hillside just south of the great evergreen forest that supplied timber for the shipbuilders of the province. Once when I was no older than five, on an outing with my father to this place, he directed my attention down valley to the long outline of the aqueduct, the arched stone flanks marching off to span the next hillside and carry on into the blue distance. The sun sat low in the sky, a tarnished disc of copper.

Look, son, he said. All of the water at our house comes from right there. Because of that aqueduct, no one has to carry heavy buckets of water just to be able to drink and bathe and wash any more, like people used to a long time ago.

He spoke that day of the precision of the grades implemented in the construction of those duct systems, a precision that assures the water always flows, uphill and down, from one town to the next. Like water through the aqueduct, his amazement conveyed itself to me.

I promise you, Antinous, that aqueduct will outlast its builders until the next ten generations of Romans have passed, at least.

Standing at his side there on the hill, my childish mind conjured an image of this line of succession of which he spokea legion of men whose sons, grandsons and further descendants all stood stacked atop each others shoulders, forming a human ladder like the tumblers in the market square might make. The ladder in my mind stretched up toward the sun, its topmost forms invisible against the zeniths brightness.

Despite illustrious ancestry and potential posterity, I grew up a small town boy, provincial and ignorant in manners and outlook. I spent much of my early childhood outdoors, herding, hunting, and observing nature, whose lessons, sensuous and cruel, she offers to any who wish to sit at her feet. I hugged those lessons to myself and pondered them in solitude, long before the years of my formal education began.

Next page