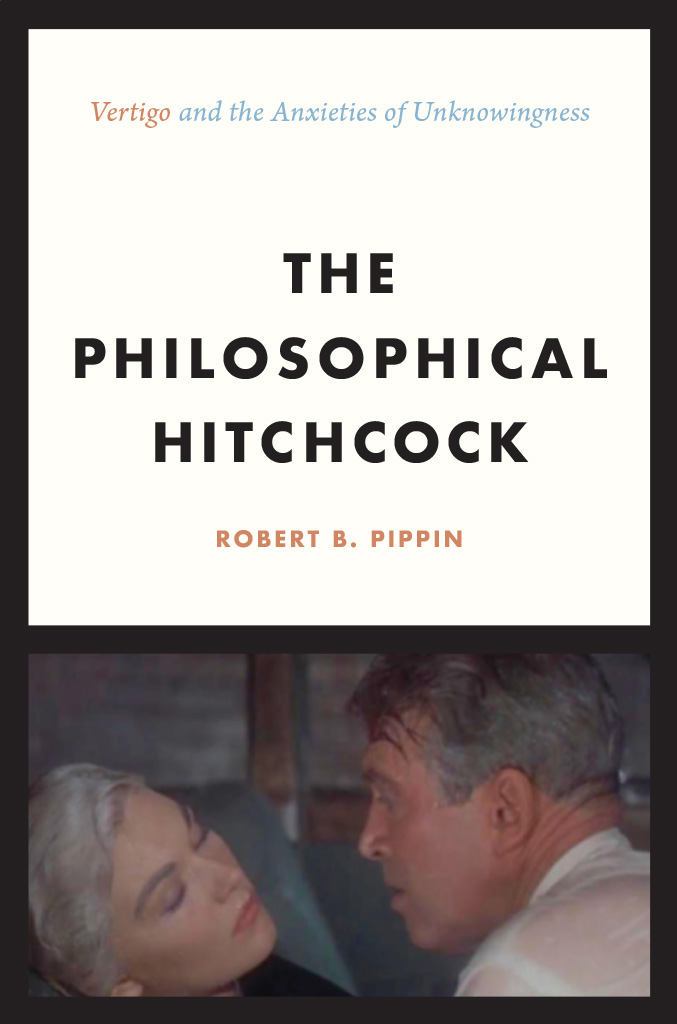

The Philosophical Hitchcock

Vertigo and the Anxieties of Unknowingness

Robert B. Pippin

The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2017 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017

Printed in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-50364-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-50378-3 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226503783.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Pippin, Robert B., 1948 author.

Title: The philosophical Hitchcock : Vertigo and the anxieties of unknowingness / Robert B. Pippin.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017001242 | ISBN 9780226503646 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226503783 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Vertigo (Motion picture : 1958) | Philosophy in motion pictures.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.P42 P56 2017 | DDC 791.43/72dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017001242

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memory of Victor Perkins

You sort of forget youre you.

Emmy, Shadow of a Doubt

Its quite remarkable to discover that one isnt what one thought one was.

Dr. Peterson, Spellbound

Who comes to seek the living among the dead?

Luke 24:5

Contents

I began writing this book while teaching a summer seminar in Switzerland with my friend and colleague Jim Conant, and I finished it sometime after we had taught a course together at the University of Chicago on Hitchcocks American films. I want to express my thanks to Professor Katia Saporiti of the University of Zurich for the invitation to deliver the seminar, and to the participants in the seminar for our lively discussions. I am yet again, as with my other two books about film, very grateful to Jim for our conversations about Hitchcock, film aesthetics, and much else over the last twenty years.

I have also had the privilege of presenting material from this book in lectures at Beloit College, Johns Hopkins, the University of Chicago, Northwestern, Berkeley, and Stanford. The discussions after the lectures were invariably lively, thoughtful, and very helpful, and I thank those audiences. I have also been helped by generous comments from Dan Morgan, Wendy Doniger, Mark Jenkins, Paul Kottman, and the late Victor Perkins, and by a number of acute comments from Fred Rush.

I wrote the final draft over part of the summer at a farmhouse in the Hudson River Valley. I am happy to express how very much I have gained from frequent conversations there about the film and related matters with Michael Fried and Ruth Leys, and how grateful I am for their valuable comments and for their friendship.

This book is dedicated to the memory of Victor Perkins, who died in July of 2016. I had been a dedicated admirer of Victors work on film since I first read Film as Film many years ago, and I then read everything else he wrote. I got to know him personally about a decade ago in Chicago, and we stayed in touch after that through correspondence and occasional meetings, in Warwick and then for the last time in Munich. We shared a love for Nicholas Ray, Max Ophls, and Hitchcock, among others, and he was always as generous and insightful a correspondent about drafts of articles and general issues as anyone I have ever known. He was also among the most humane, kind, and forthright people I have ever met. To say of someone that he was a lovely person can sound quite indeterminate, but anyone who had the great good fortune to have known Victor will know exactly what I mean.

White Oak House

Buskirk, New York

July 2016

As the book title indicates, I am proposing a philosophical reading of Hitchcocks Vertigo. My goal is to offer an interpretation that shows how the film can be said to bear on a philosophical problem, the problem I set out in this and the following section. This proposal immediately involves two enormous questions: what philosophy is, such that a film could be said to bear on it; and how an art object, a film in particular, must be conceived such that it could intersect with, bear on, philosophy. Several other unmanageable questions immediately arise. Stanley Cavell has said that what serious thought about great film requires is humane criticism dealing with whole films,

To try to address such questions in an opening section and then move on would obviously be foolish. But, given the proposal, some statement of principles (and nothing like a defense of the principles) is in order. So I briefly offer a summary of such commitments, but only that.

Consider first the conditions that must obtain for a cinematic experience to be an aesthetic experience, an experience uniquely directed at, informed Or, at least, this is how I understand his claim, not how he puts it. That is, we are not seeing actors on a big screen and, in a second step, imagining them being fictional characters (that is how he puts it).

It is also not the case that attending aestheticallyof knowing what we are doing when we are experiencing, attending to, the workis something that interferes with or competes with our direct emotional absorption in the plot. We can start watching a movie with the assumption that its ambition is merely to entertain us; we thus attend to it in such a way, take ourselves to be having such an experience. But then someone points out for us that there are elements in the movie that might be entertaining but also raise questions beyond plot details, questions that cannot be explained by that function alone. We then attend to the movie in a different way, a way I want to follow Wilson in continuing to call imaginative seeing, or, in the terms used above, aesthetically attending, but which now also requires interpretive work. We dont, in such a case, lose interest in the plot and become interested in another issue. (The same sort of parallel track attending is possible in admiring the performance of an actor even as we follow and try to understand what the character is doing. The main point is the same. There are not two steps: seeing the actor and imagining the character.)can say, then, that the imagination or attending in question is not limited to an emotional involvement in the events we see (and in what might happen) and in the events and motivations in the world of the film, but it ranges over many elements, as we try also to imagine why we are shown things just this way. When that happens, we attend aesthetically in a different register, see imaginatively, an attending that now includes an interpretive task.

Giving a formulaic account of just what in the work demands such closer interpretive attending is not easy. At least it is hard to point to anything beyond this abstract appeal to questions raised by the work, which are not questions about plot details but are questions like, Why are we so often looking from below at figures in shadows in some film noir? Or, What does it mean that Gary Coopers character throws his marshals badge to the ground in obvious disgust at the end of

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).