Original cloth editions published by Charles E. Tuttle, Rutherford, Vermont, and Tokyo, Japan, 1957

First paperback edition published by the Combined Asian-American Resources Project, Inc., Seattle and San Francisco, 1976; distributed by the University of Washington Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

FOREWORD

DEAR JOHN OKADA,

I'm writing to you across time, as one writer to another, to congratulate you on the reissue of your groundbreaking novel, No-No Boy. The University of Washington Press has done me the honor of asking me to write a new foreword to your book, and to tell you the truth, I'm nervous. I wish I could consult with you, or visit you and ask you for your blessing, but I can't.

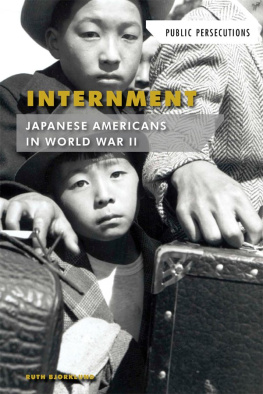

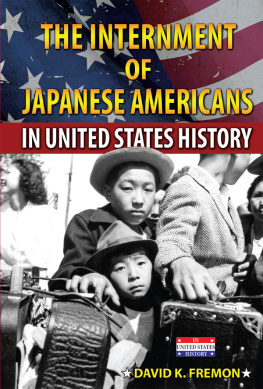

You probably don't even know that your novel was groundbreaking. When it was published, back in 1957, you probably thought it was a colossal failure. It's hard enough to write a novel, and harder still to get one published, but then to have it so completely ignoredthis must have been crushing. Your original publisher, Charles E. Tuttle, was based in Tokyo, which I'm sure didn't help your chances for success in North America. The few critics here who bothered to review it pretty much panned it. They bitched about your bad English and said it wasn't literature. Even Japanese Americans shunned it. It seems they were embarrassed by it, which sounds crazy now, but in retrospect I suppose I understand why. In No-No Boy you wrote unflinchingly about the scarring experience of being a Japanese American on the West Coast during World War II, but that war had only ended twelve years earlier, and twelve years is no time at all. When your bookcame out, Japanese Americans were busy keeping their heads down, assimilating, and working on becoming the model minority of 1950s America. It's understandable. They had been rounded up and sent to prison camps in the desert. They had lost their homes and businesses and communities. They had suffered, and they wanted to move on. No-No Boy was radical, but it was ahead of its time. It was angry and raw. It touched nerves and opened wounds. It reminded them of a past they wanted to forget, and so they rejected it. Your book disappeared almost overnight.

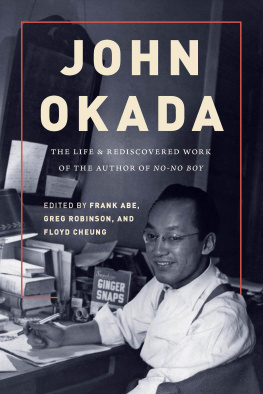

Of course, you don't need me to tell you all this. You probably spent those years after publication thinking about what had happened, turning it over in your mind, trying to understand why your book had failed to find readers. To some extent, it must have broken your heart, and I'm guessing this is so because you never wrote another.

But what you don't know is this: twelve years after its initial publication, a guy named Jeff Chan found a copy of your book in a Japantown bookstore in San Francisco, and he started passing it around to his Chinese American and Japanese American literary buddies, and little by little, they grew passionate about it. They formed a group called CARP, the Combined Asian-American Resources Project, and finally, in 1976, they reissued your book. And this time, people paid attention.

Two decades had passed, and the world had changed. The civil rights movement had made huge gains. Americans were talking about racism and discrimination. Japanese Americans were starting to speak out against the internment and criticize the United States government for its unconstitutional policies during the war. There was even the beginning of a reparations movement for internees. By 1976, people were ready for your book, and they read it and loved it and were inspired by it. And this should have been a wonderful moment for you, seeing your book republished and appreciated, and your passion for writing vindicated at last, but sadly it was not as wonderful as it should have been because you were dead.

When you died in 1971 of a heart attack, at the age of forty-seven, you still thought your novel was a failure, and I'm truly sorry about that, and I'm writing this now to tell you that it wasn't. No-No Boy has the honor of being the first Japanese American novel, and among the first of what has become an entire literary canon of Asian American literature. You broke the ground for us, John Okada, and now, in 2014, we're celebrating you again. I just wish you were alive to enjoy this moment.

Your book and I are about the same age. I was born a year before No-No Boy was published, and I hope you'll forgive me for not reading it then, but I had only just turned one and wasn't reading yet, and the book disappeared from the bookshops pretty quickly. When your novel was reissued in 1976, I was twenty and quite a good reader, but I'm afraid I still didn't read it. This is harder to explain, but the fact is that I wasn't very interested in the Japanese American cultural movement at the time. I didn't think of myself as Japanese American, even though my mother was Japanese and my father was Anglo American. I saw myself as mixed race, half, or half-Japanese instead, and I was growing up in New England, where there were relatively few Asians. The whole Japanese American cultural movement seemed like a west coast thing, heavily defined by the internment experience, and while my grandfather had been interned and my mother put under house arrest, all those World War II stories just seemed like ancient history to me. Now that I'm older, I have a different perspective on time, but when we're young, we think time starts with us.

When I finally did read your book, at the age of forty-something, I was stunned. I'd grown up in the shadow of World War II. I knew about the internment, and I had a general sense of the world you describe in the novel, but I'd never felt it before. Your novel made me feel it. The way you told Ichiro Yamada's story shocked me into realizing how profoundly shaped I'd been by the normative postwar assimilationist values that were so prevalent among peopleof Japanese heritage living in America, including my own family. This may sound unbelievable, but I'd never realized, until I read your novel, that a Japanese American could be angry. Mad with rage, or just plain crazy! I thought the Japanese American emotional palette comprised more neutral shades: resignation, obedience, forbearance, sadness, nostalgia, regret.

Reading No-No Boy reminded me that historyand in this case, a history I thought I knewis so much more than just facts.