THE SCOTT AND LAURIE OKI SERIES

IN ASIAN AMERICAN STUDIES

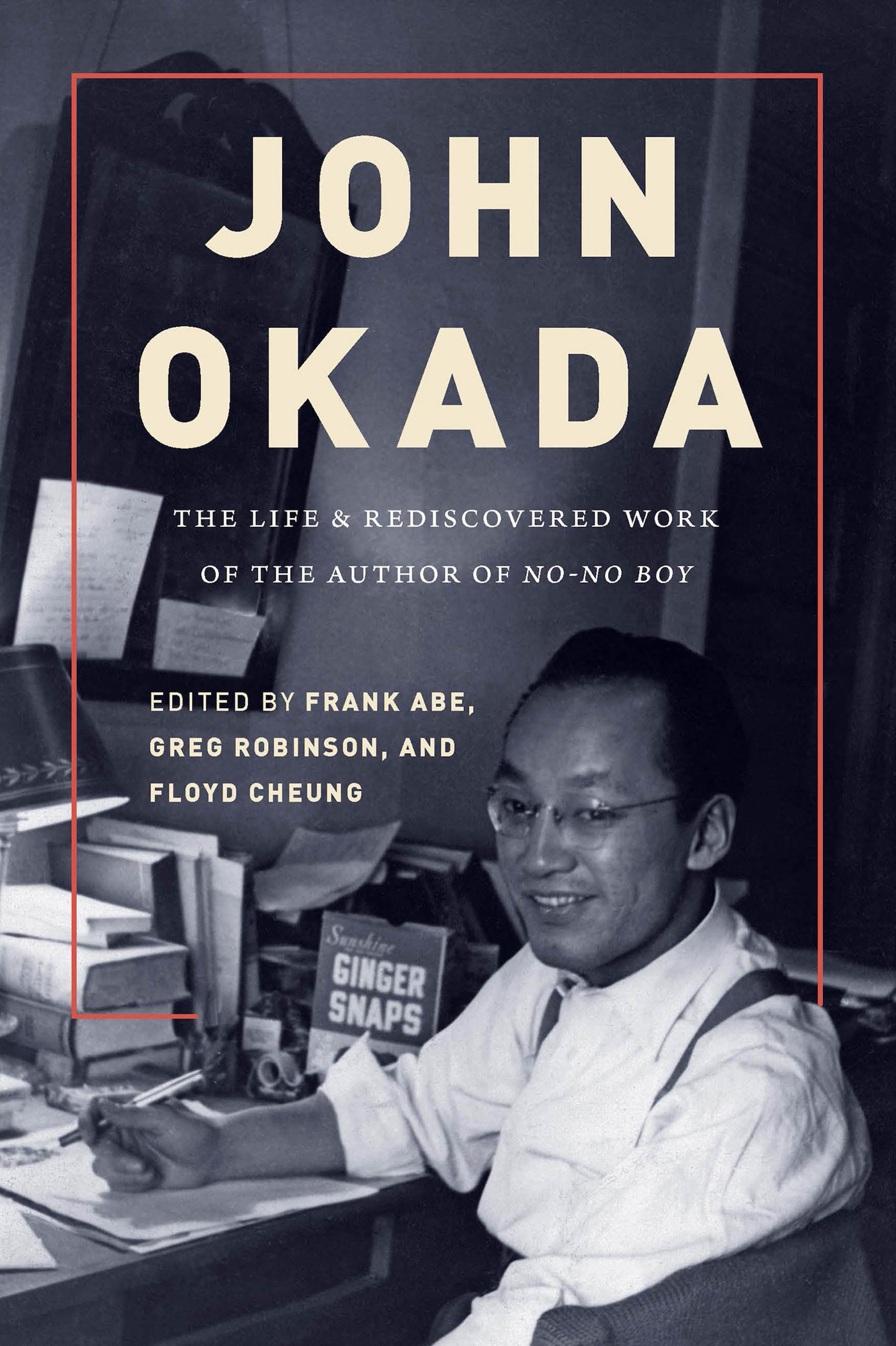

JOHN OKADA

THE LIFE & REDISCOVERED WORK OF THE AUTHOR OF NO-NO BOY

EDITED BY

FRANK ABE, GREG ROBINSON, AND FLOYD CHEUNG

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

Seattle

John Okada was supported by a grant from the Scott and Laurie Oki Endowed Fund for publications in Asian American Studies.

Copyright 2018 by Frank Abe, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung

Printed and bound in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1

Design by Katrina Noble

Composed in Arno Pro, typeface designed by Robert Slimbach

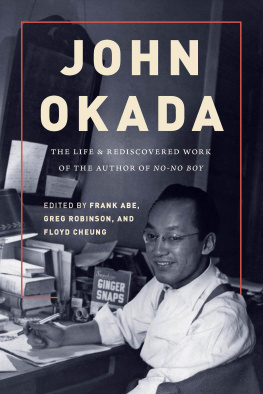

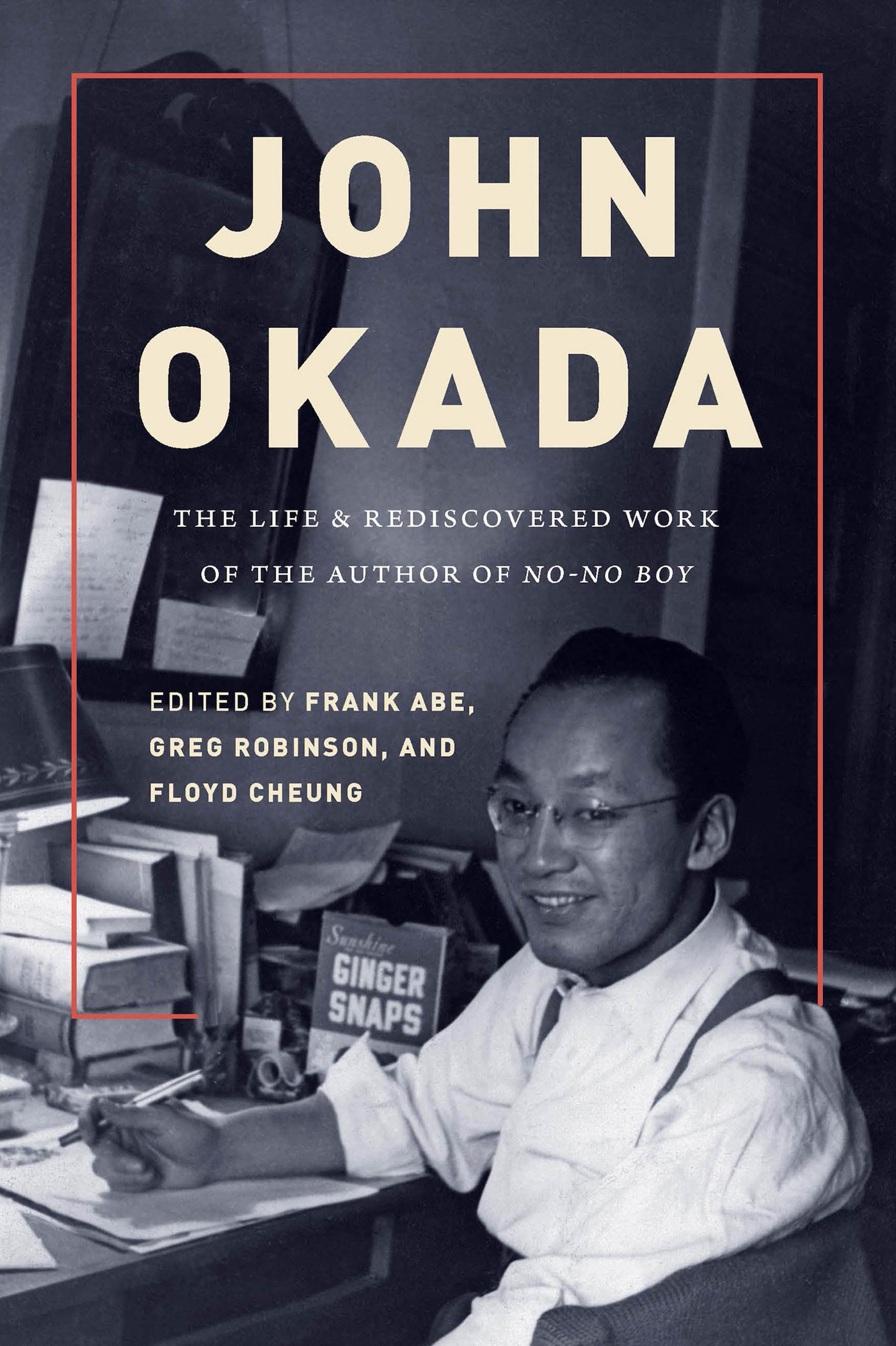

Cover photograph: Okada enrolled at Teachers College in New York City to get a masters degree to teach English. It was here he reportedly sketched the first scenes for No-No Boy in early 1949. (Yoshito Okada family)

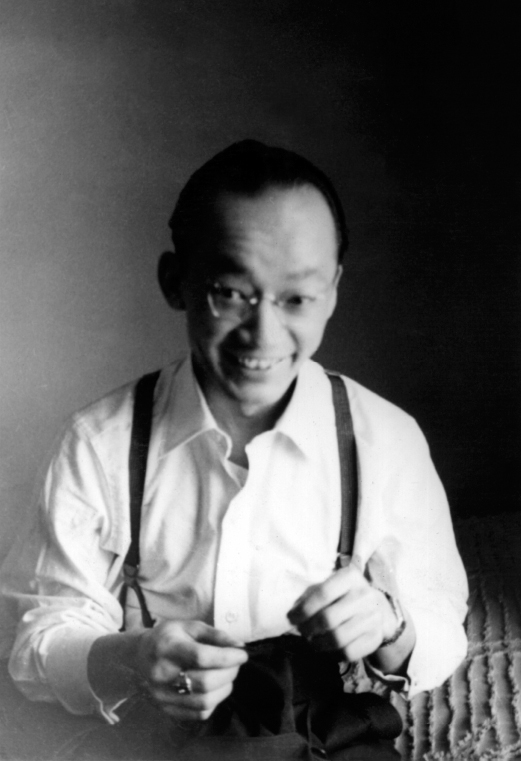

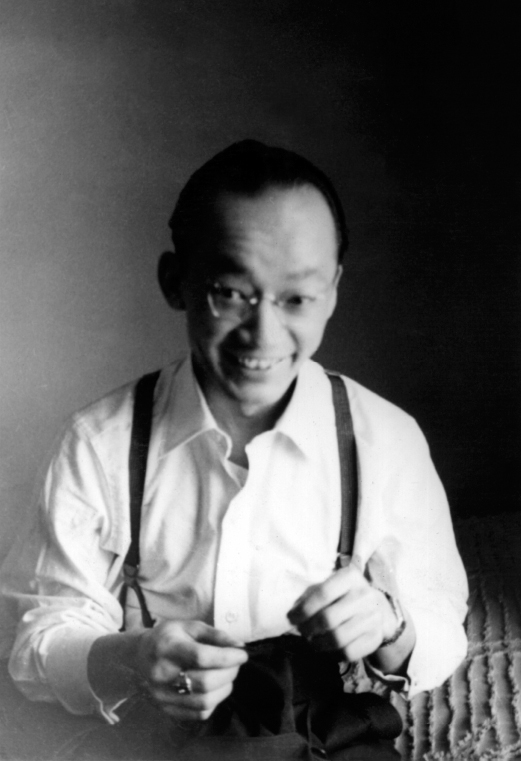

Frontispiece: Okada mugged for the camera in spring 1949, around the time he was ready to graduate from Teachers College. (Yoshito Okada family)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON PRESS

www.washington.edu/uwpress

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Abe, Frank editor. | Robinson, Greg, 1966 editor. | Cheung, Floyd, 1969 editor. | Okada, John. Works. Selections.

Title: John Okada : the life and rediscovered work of the author of No-no boy / edited by Frank Abe, Greg Robinson, and Floyd Cheung.

Description: Seattle : University of Washington Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003963 (print) | LCCN 2018011915 (ebook) | ISBN 9780295743530 (ebook) | ISBN 9780295743523 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780295743516 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Okada, JohnCriticism and interpretation.

Classification: LCC PS3565.K33 (ebook) | LCC PS3565.K33 Z69 2018 (print) | DDC 813/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003963

I Must Be Strong; When in Japan: A Comedy in One Act; What Can I Do?; Without Solace; Skipping Millions; The Silver Lunchbox; and Heres Proof! copyright Dorothea Okada and Matthew Okada. Reprinted by permission.

The High Cost of Proposals and Presentations was originally published in Armed Forces Management (Ziff-Davis, December 1961). The Technocrats of Industry was originally published in Armed Forces Management (Ziff-Davis, March 1962). Copyright Ziff-Davis. Reprinted by permission.

Nightsong in Asian America copyright 1972, 1974 by Lawson Fusao Inada. Originally published in Yardbird Reader, vol. 3 (Berkeley, CA: Yardbird Publishing Cooperative, 1974). Reprinted by permission.

For Dorothea and Matthew

America is a country which has made mistakes and will make more but, at the same time, it is a country which is striving constantly to rectify the conditions which breed those mistakes.

JOHN OKADA

letter to Meredith Weatherby

FEBRUARY 14, 1956

CONTENTS

FRANK ABE

FRANK ABE

FLOYD CHEUNG

GREG ROBINSON

STEPHEN H. SUMIDA

MARTHA NAKAGAWA

JEFFREY T. YAMASHITA

SHAWN WONG

LAWSON FUSAO INADA

FRANK ABE

JOHN OKADA

Introduction

Saying No! No! to the Community Narrative

FRANK ABE

THIS BOOK SEEKS TO RECOVER THE LITERARY VISION OF JOHN Okada, a pioneering American novelist whose unpublished work was lost to an early death and a widows grief. Okada was a Nisei, second-generation Japanese Americanthe child of immigrantsand two passages of writing bookend his pursuit of what he and his peers envisioned as the Great Nisei Novel.

He tried his hand instead with poetry. The result, still unorganized and disunified, is the first surviving piece of creative writing we have by John Okada (reprinted here as I Must Be Strong). In it, he confronts the

Fast-forward to 1957. Now in Detroit with a family of his own, the thirty-four-year-old Okada wrote with the authority of experience. DECEMBER THE SEVENTH of the year 1941 was the day when the Japanese bombs fell on Pearl Harbor. As of that moment, the Japanese in the United States became, by virtue of their ineradicable brownness and the slant eyes which, upon close inspection, will seldom appear slanty, animals of a different breed. The moment the impact of the words solemnly being transmitted over the several million radios of the nation struck home, everything Japanese and everyone Japanese became despicable.

By then, Okada had seen how guilt by association led to betrayal by the federal government, the eviction of 110,000 Americans of Japanese ancestry from their homes on the West Coast, and their four-year incarceration in American concentration campsa mass violation of civil protections under the Constitution. Okada himself stayed strong: he left camp early for college, then joined the Military Intelligence Service and flew twenty-four reconnaissance missions in a B-24 over the Japanese coastline. Immediately after the war he earned degrees in English and librarianship, and wrote some short fiction.

From these experiences, John Okada created the voice of No-No Boy. Brought out in a tiny edition by a small-scale publisher of works on Asia, it received little attention at the time. Yet No-No Boy emerged after its authors premature death to become a much-studied and celebrated work of American literature.

THE WRITER AS RESISTER

The power of No-No Boy derives from its portrait of the unexpressed rage of the Nisei at their unjust imprisonment, which collectively disinherited them as a generation through the combined losses of homes, farms, and businesses. After having been gone four years, two in camp and two in prison, draft resister Ichiro Yamada returns to Seattle to find his community fragmented and its people divided against one another by the nations wartime demand for proof of loyalty. Parents mourn sons lost in battle; veterans return maimed and succumb to their wounds; a woman abandoned by her soldier husband finds comfort in Ichiros arms; his mother goes mad when forced to admit that Japan lost the war.

When published in 1957, everything about this story challenged the overall amnesia about the camps and the prevailing values of Okadas own community, which mostly wanted to forget and fit in. The Nisei adopted the guise of Quiet Americans, a public face codified by the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL), a social and political federation of Nisei professionals led just before the war by president Saburo Kido and national secretary Mike Masaoka. After Pearl Harbor, the JACL fingered Issei leaders for arrest, waived the Nisei right to protest eviction, and cooperated in the communitys removal and incarcerationall as proof of loyalty to the government. The organization did support select legal challenges, but the overriding JACL response to mass incarceration could be captured in two phrases: shikataganai, Japanese for it cant be helpedpassive resignation in the face of injustice; and go for broke, Hawaiian pidgin for shoot the works, give 110 percentpatriotic self-sacrifice and the spilling of ones blood to prove ones loyalty. And when several hundred incarcerees defined as loyal by the government contested their incarceration in 1944 by refusing to be drafted from camp, the JACL collaborated with the government to crack down on dissent.

Next page