DRAWING AND PAINTING TREES

CHAPTER 1

ORNAMENTAL

IT is impossible to assign any date to the introduction of tree forms in the pictorial records of the ancients. The inquiry may be delegated to the archaeologist and the antiquarian. We know that the primitive artists were primarily concerned with making representations of human beings and animals; that houses, temples, and the work of mans hands had prior claims to the beauties of Nature; that the Greeks were absorbed in the reproduction of gods, warriors, and hunters; and that, in a later age, the advent of Christianity caused the activities of all professional painters to be mobilized for the service of the Church.

The earliest examples of the Italian school of painting show it to have been a nursery of religious art, its output consisting mainly of pictures of Christ, of the Holy Family, the Virgin, and the Saints. The compositions were commissioned or acquired by the Church. The work of the artist was restricted to altar-pieces, panels, and Church decorations, and was dictated as to subject and treatment by his only patron.

But, although the conditions under which the pictures were produced were so rigid as to preclude practically all initiative or innovation on the part of the craftsman, it is evident in the earliest examples of the Florentine, the Sienese, and the Umbrian Schools from the National Gallery that the painters realized the value of landscape as backgrounds for their compositions and delighted in introducing a touch of Nature to give variety to their designs.

The first experiments were tentative, but the forms borrowed from Nature gained steadily in decorative significance, and the modest saplings and formalized shrubs to be seen in the paintings of the fourteenth century developed in the course of the following two centuries into beautiful, realistically painted, fully-grown trees.

Ruskin must be regarded as a little hypercritical in his comments upon the efforts of the early Italians in the realm of landscape. He admits the care with which they laboured to portray the simple aspects of Nature, but he describes them as painters of tree-portraits rather than landscape painters. He insists upon one very important principle that Nature observes in her foliageShe always secures an exceeding harmony and reposebut, instead of commending the ancients for the fidelity with which they copied Nature in this respect, he complains that they content themselves in their religious pictures with impressing on the landscape perfect symmetry and order such as may seem consistent with, or induced by, the spiritual nature they would represent.

It is true, as Ruskin observes, that in their representations of tree forms they excluded all signs of decay, disturbance, and imperfections, and that in so doing they conveyed an impression of unnaturalness and singularity, but their purpose was to invest all their accessories, including Nature, with something of the spiritual exaltation they were striving to express. The trees, in many instances, are strictly upright and equally branched on each side, and their slight and feathery frames frequently suggest that they have never encountered blight or frost or tempest; and when roses and pomegranates appear in their pictures the leaves which twine themselves in fair and perfect order about delicate trellises are drawn to the last rib and vein. But may it not be argued that these peculiarities only prove that the ancients were appreciative of Natures success in achieving harmony and repose?

The following very brief survey of the progress of landscape painting through the ages is compiled from the examples exhibited in the National Gallery and, to a lesser extent, the Tate and the Victoria and Albert Galleries and the British Museum in London. I have deliberately confined myself to these sources as being readily accessible to English students, and as offering a really splendid collection of pictures which are entirely adequate for the purpose. (Unless otherwise stated, the numbers given apply to the National Gallery.)

A very interesting example of early tree forms among the pictures of the Florentine School in the National Gallery is No. 2508, in which five different trees are placed by the unknown artist behind the figures of the Virgin and Child and Angels. Each tree has a characteristic silhouette and a distinguishing leaf formation. The artist was clearly concerned to obtain variety of form. The cypresses and palms are painted with great confidence, and the intense care by which the result is obtained is to be noticed.

In Noli me Tangere (No. 3894), Jacopo di Cione (13081394.) has with partial success filled in his background with three little trees, outlined against the sky and densely covered with leaves, painted in detail and to a well-defined pattern. It is interesting to observe that the same type of tree is used in the middle distance and the foreground, and that, by some whim of inverted perspective, the tree nearest to the spectator is the smallest of the five.

Orcagna (13081368) has made use of trees in five of the six parts of his altarpiece (Nos. 573578). Tight in their leaf formation, decoratively rounded in outline, destitute of branches and relying on the main stem to support the mop-like head of foliage, these grim and effective symbols are placed with an eye to the design and are painted with primitive conviction.

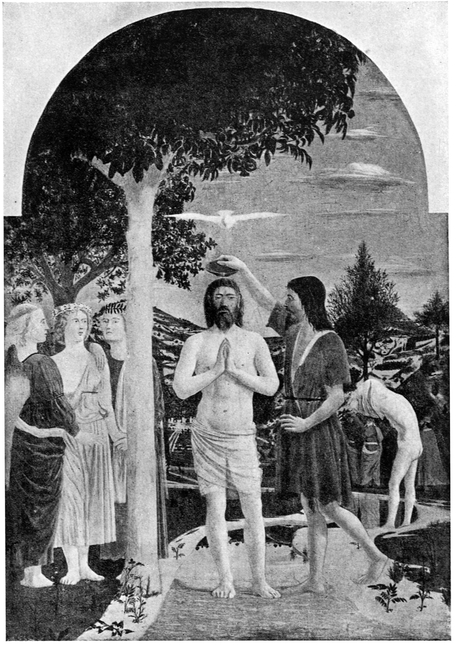

Pisano (13991455), in his Saints Anthony and George (No. 776) has placed a pine wood in the background, strongly silhouetted against a light sky. Piero Della Francesca (14161492) displays an intimate knowledge of tree form and construction. In his beautiful composition Baptism of Christ (No. 665), two handsome trees, which are plainly identifiable as pomegranates, occupy a prominent position in the picture. The colour of the bark, the grouping of the foliage which forms a floral canopy over the figure of Christ, and the outspreading upper branches of the companion tree are faithfully observed and lovingly notated (see page 5).

In the same artists The Nativity (No. 908), our vision is directed to the miniature landscape behind the sunlit cattle-shed, and we are puzzled by the unique tree-forms which are dotted over the distant hills. It would be difficult to label them. Curious in their cultivated form and ornamental patterns, they would appear to be incorporated with an idea of presenting growths which were typical of the painters locality.

THE BAPTISM

By Piero Della Francesca

It would prove too long a task to follow in chronological detail the evolution of tree painting in these works of the early Italian painters, but it is hoped that these brief references to some of the more striking examples will stimulate the student to follow up the line of investigation for himself.

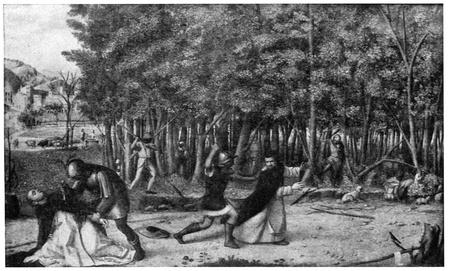

DEATH OF S. PETER MARTYR

By Giovanni Bellini (Studio)

While evidence is not lacking of a desire to introduce variety of tree forms into some of these early paintings, the artists were usually content to repeat the accepted symbols, and the same formula for tree decoration is employed in many works. A popular device is the representation of a slim sapling, resembling a young ash, which figures in A Young Man (No. 1035), by Franciabigio, in Bartolommeo Bianchini (No. 2487), by Francia, and again in his picture Pieta (No. 2671). This tree appears again in Fiorenzo di Lorenzos Virgin and Child (No. 2483), and in Costas Virgin and Child with Saints (No. 629). The Virgin and Child (No. 2906)School of Botticellipresents a somewhat more substantial growth. This is also introduced on the right of the picture of Virgin and Child with St. John (No. 1412), and use is here made of the dense silhouette of dark green, larch-like trees such as are seen in Pisanos paintings.