Series 117

This is a Ladybird Expert book, one of a series of titles for an adult readership. Written by some of the leading lights and outstanding communicators in their fields and published by one of the most trusted and well-loved names in books, the Ladybird Expert series provides clear, accessible and authoritative introductions, informed by expert opinion, to key subjects drawn from science, history and culture.

The Publisher would like to thank the following for the illustrative references for this book: : top chart: Iapetus Fossil Evidence courtesy of Wouldloper via Wikimedia Commons; bottom map: Permit Number CP17/078 British Geological Survey NERC 2017. All rights reserved.

Every effort has been made to ensure images are correctly attributed; however, if any omission or error has been made please notify the Publisher for correction in future editions.

MICHAEL JOSEPH

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Michael Joseph is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Text copyright Iain Stewart, 2018

All images copyright Ladybird Books Ltd, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration by Ruth Palmer

ISBN: 978-1-405-93073-4

Iain Stewart

PLATE TECTONICS

with illustrations by

Ruth Palmer

Earth puzzle

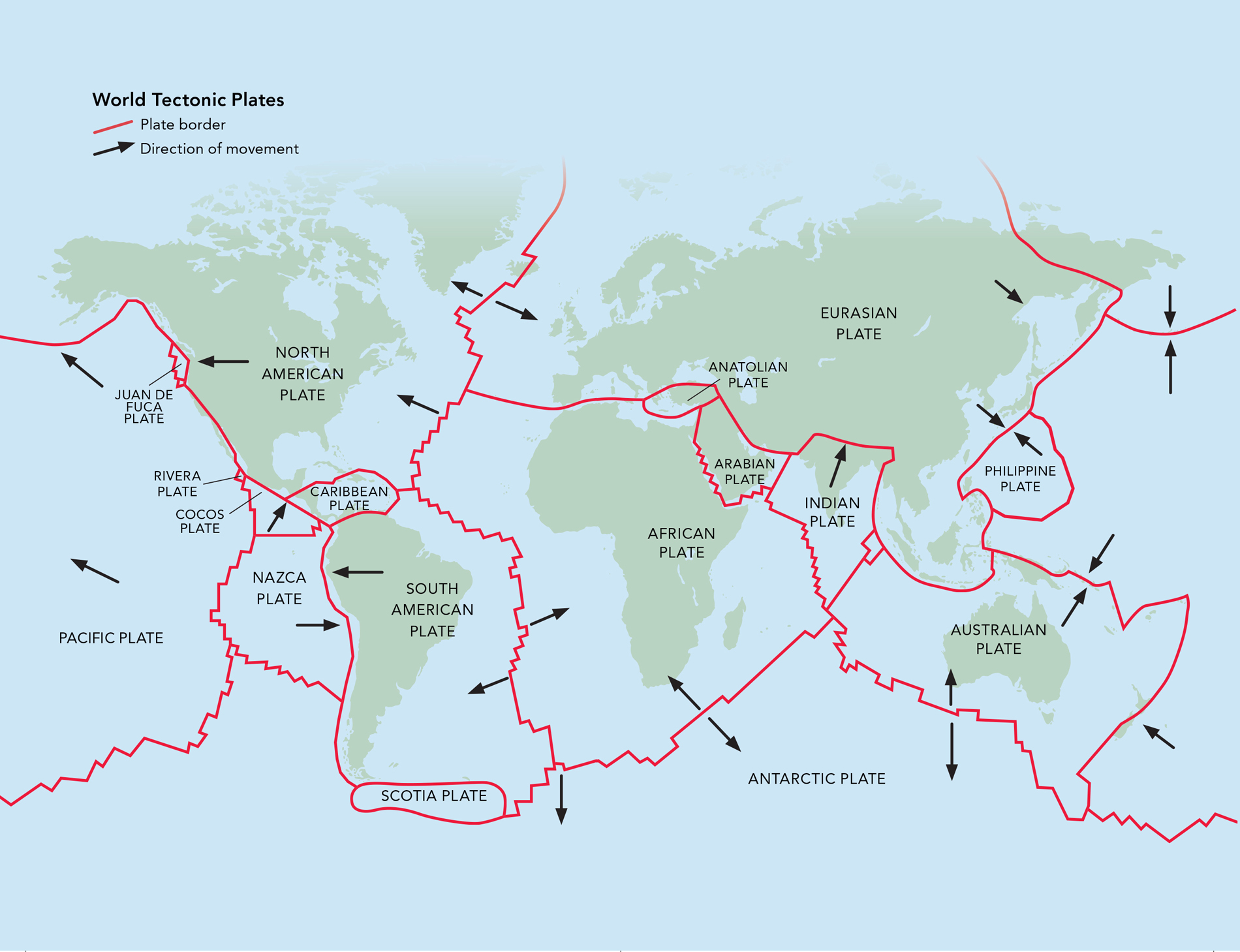

Our earth is a puzzle the product of a planetary experiment that was run once only and lasted four and a half billion years. Unravelling that succession of worlds which has unfolded until the present would seem to be a task of impossible complexity. For centuries, scientific enquiry had grappled with convoluted ideas to explain the earths natural features: its continents and oceans, mountains and valleys, volcanoes and earthquakes.

Then, over the course of just a few years in the 1960s a geological instant it was all over. A small group of geophysicists some leaders in the field, many just out of graduate school working at a handful of international institutions, formulated the first global theory ever to be generally accepted in the entire history of earth science. Like all grand unifying theories, it would turn out to be deceptively simple.

Today, half a century on, it is hard to imagine thinking about our planet without the lens of plate tectonics. The theory not only sits at the heart of our scientific understanding of how the earth works, it has infiltrated into everyday life. People talk of the moving plates of politics or tectonic shifts in world affairs. But few other than earth scientists appreciate the deep roots and revolutionary currents that led to what would be one of the greatest scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century.

This is the story of the science and scientists that made earth history.

Voyages of discovery

Throughout the sixteenth century, successive waves of Portuguese and Spanish seafarers charted the outer reaches of the known world. These grand voyages of discovery revealed an earth that was more ocean than land, had distinct climate zones and wind patterns, and exhibited a geomagnetic field.

Back home, European map-makers converted these maritime charts into ever more intricate and accurate world views. One, the renowned Flemish geographer Abraham Ortelius, noticed a curious transatlantic twinning. In his Thesaurus Geographicus (1596), he noted that western Europe and Africa seemed to project into the recesses of the American continent. Brazils eastern bulge seemed to fit snugly into the bight of West Africa, the Saharas western bulk could rest against North Americas eastern shores, and Canadas Nova Scotia and Newfoundland appeared to slot into the Bay of Biscay and the English Channel.

By the nineteenth century, speculation about the origin of the earths enigmatic natural features was the pastime of gentleman scientists and scholarly clergymen. Scientific theories were generally thinly veiled biblical thinking, often invoking divine violence. In 1838, the Reverend Thomas Dick, a Scottish minister and philosopher, wrote that the pairing of Atlantic shores renders it not altogether impossible that the continents were originally conjoined and that, at some favourable physical revolution or catastrophe, they may have been rent asunder by some tremendous power, when the waters of the ocean rushed in between them and left them separated as we now behold them.

Abraham Ortelius with a later depiction of his idea.

Greater glory

March 1912: Robert Falcon Scott and his team are returning from their ill-fated attempt to be the first to the South Pole. Blighted by frostbite, snow blindness and malnutrition, and man-hauling 16 kg of rock samples, they still take time to geologize the Transantarctic Mountains. Ultimately, it would cost them their lives. Almost eight months later, when their frozen bodies were found, Scotts rock samples were carefully laid out. He had clearly considered them precious cargo.

Scott had been persuaded to collect the rocks by a young English palaeobotanist, Marie Stopes. Later in life she would find fame as a pioneer of womens rights and family planning, but in the early 1900s she was an expert on ferns and seed plants from Carboniferous times, 300 million years ago. Certain that such rocks would be found in Antarctica, she had pleaded with Scott to take her on his expedition. He refused, but promised to bring her back some samples.

When analysed back in England, Scotts samples were found to be packed full of fossilized plant debris. Many of the leaves were from a fern-like tree called Glossopteris, indicating that in the Carboniferous age, this icy wasteland had been carpeted with temperate forest. The spores of these trees couldnt be transported great distances but Glossopteris had been found in Carboniferous strata right across the southern hemisphere, from India to South America. All those land masses must once have been welded together, including, now, Antarctica. Scotts rocks had helped to define the southern extent of an extraordinary land mass.

The face of the earth

Earlier, in the 1850s, the Vienna-based geologist Eduard Suess had discovered an ocean lurking amid the magnificent Austrian Alps. Finding thick piles of ancient sediment identical to that accumulating on the modern sea floor, he proposed that a primeval marine basin the size of the Atlantic had once dominated the heart of Europe. Suess named it Tethys, after the sister and consort of the Greek god of the ocean, Oceanos. Suesss crumpled Alpine peaks were testimony to slow constriction of the Tethys Ocean by the northward advance of a great land mass to the south.