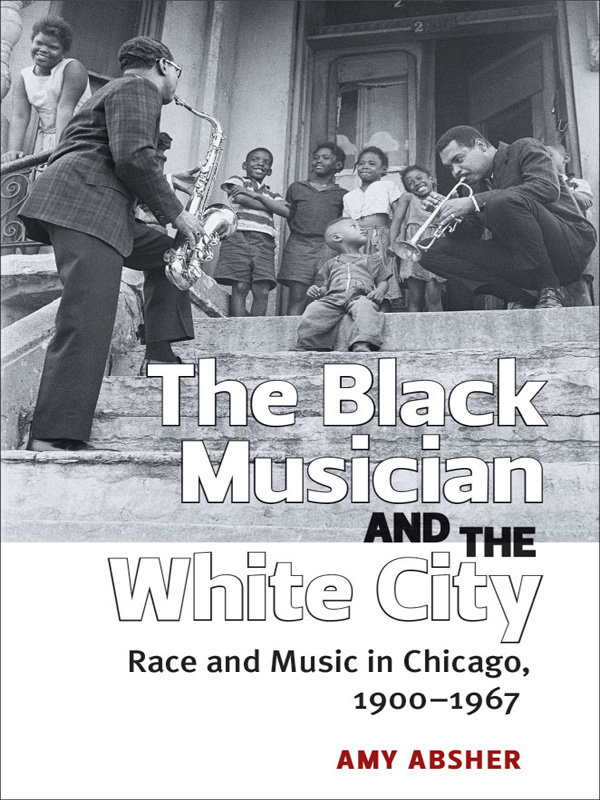

Absher - The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967

Here you can read online Absher - The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: The University of Michigan Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Absher: author's other books

Who wrote The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Page i Page ii Page iii

Page i Page ii Page iii RACE AND MUSIC IN CHICAGO, 19001967

Amy Absher

The University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright by the University of Michigan 2014

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by

The University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

Printed on acid-free paper

2017 2016 2015 2014 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Absher, Amy. The black musician and the white city : race and music in Chicago, 19001967 / Amy Absher.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-472-11917-2 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-02998-3 (e-book)

1. African AmericansIllinoisChicagoMusicHistory and criticism.

2. Popular musicIllinoisChicagoHistory and criticism. 3. Popular musicSocial aspectsIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 4. Music and raceIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 5. African American musiciansIllinoisChicago. 6. Music tradeIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 7. African American musiciansLabor unionsIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. 8. MusiciansLabor unionsIllinoisChicagoHistory20th century. I. Title.

ML3479.A26 2014

780.89'96073077311dc23

2013040288

Page vTo Charles Walton and Edward O. Bland

Page vi Page viiThis project would have been impossible without the financial support of the history department at the University of Washington and the SAGES program at Case Western Reserve University. I wish to express my sincere appreciation to my graduate advisor, Professor John Findlay, who made all things achievable. I would also like to thank my committee membersProfessors Quintard Taylor, Marc Seales, and the extraordinary Carol Thomasfor their friendship, guidance, patience, and support.

I owe a great debt to librarians, archivists, artists, preservationists, and researchers who shared their expertise and opinions and showed me how to realize this project. They include the essential Theresa Mudrock and the indomitable Suzanne Flandreau as well as Andy Leach, Janet Harper, Joe Bartl, Dale Mertes, Morris A. Phibbs, Horace Maxile Jr., Richard Schwegel, Frank Latino, Melanie Zeck, Jennifer Phelps, and the staff of the Harold Washington Library's music collection. They represent an essential academic resource to all scholars that is now being underfunded by shortsighted university and institutional planners looking to make up budget shortfalls. Without properly funded and staffed libraries and archives, studies such as this one might not be possible in the future.

In addition, I am grateful to Professor James Grossman, Professor Leon Fink, The Dr. William M. Scholl Center for American History and Culture at the Newberry Library, the Center for Black Music Research, the Archdiocese of Chicago, and International House at the University of Chicago for providing me with access to a community of scholars in Chicago. Particularly, I would like to single out my colleagues from the Newberry Library's Urban History Dissertation Group: Tamsen Anderson, Phyllis Santacore, Marygrace Tyrrell, David Spatz, Ed Miller, Jennifer Page x Vanore, and Jessica Westphal. Their assistance raised the level of scholarship in this project.

My life in Chicago was eased greatly by the assistance of my friends at I-House. In this regard, I owe special thanks to Maria Accosta, Norberto Lopz, Martha Sosa, Jeanette Doss, Burt Doss, Undre Moore, Dolores, Deborah Jones, and Wally Thomas.

I feel privileged to have been mentored by Edward O. Bland and Tom Crown. Professors Scott Casper, David Ake, Eric Porter, Margaret Urie, Mehdi Etezadi-Amoli, Richard Johnson, William Rorabaugh, and Jon Bridgman will no doubt see their influence on this work. I hope they will be proud. Furthermore, I count myself fortunate to have had the support of the faculty and staff in Case Western Reserve University's SAGES program: above all, my boss Peter Whiting, John Orlock, Janet Alder, Sharmon Sollitto, and Carrie Kurutz. Arthur Evenchik deserves special thanks for bringing me to Case and for assisting me in editing this book. Likewise, I am grateful to my friends at the Dittrick Medical History Center, Jim Edmonson and Jennifer Nieves, who have given me their friendship and an intellectual home in Cleveland. I am also thankful for the friendship and support I have found in Case's history departmentespecially Professors Jonathan Sadowsky, Alan Rocke, John Broich, Ken Ledford, Jay Geller, and Wendy Fu. In addition, I am lucky to have had the support of my students. At Case, Samuel Esterman and Selvaanish Selvam became essential to the completion of this book. At UW, Kelley Mao, Erin Andersen, Zach Takasawa, and Sarah Goethals all wrote me letters and cards to encourage me while I was working on my dissertation in Chicago.

As with all books, the project would have been impossible had it not been championed by a book editor. Chris Hebert saw potential in the work when all it was an abstract. Marcia LaBrenz was the project manager who saw the publication process through to completion. I wish to thank them, along with the press's staff, for their guidance and hard work, and for their ability to imagine the end results.

Then there were the friends. Mariana Gatzeva, Keiko Kirby, Vincent Howard, Emmie Vance, Justyna Stypinska, Roey Moran, Tim Blake, Guatam, Janel Fontana, Dave Bryant, Henry Ramirez Le Maire, Rosina Mora, Liz Johnson, Brian Casserly, Brian Schefke, Tristan Goldman, Chris Herbert, Scott Brown, Sasho, Mary Geiger, Mitzi Melendez, Daniel Morales, Derek Botha, Qiyan Mao, Nori, Rob Walsh, Abby Adams, Bea, Jim Page xi Lea, John Mills, Jack Carver, Andrew Price Jr., Simeon Man, Stella Yee, Miriam Llorens Lopz, Joe Frank, Shawn Tallant, Jill Koehler, Jeri Park, Jenn Weiss, Rachel Kapelle, Annie Cardwell, Elanda Goduni, Jon Hess, Elizabeth Doolittle, Mika Little, Joshua Sylvan, Ben Cook, Digby, Alex Shappie, Brittany Byrd, Conrad Moore, Steven Cramer, Jennifer Barclay, Michele Hanks, Michele Myers, Cheryl Glotfelty, Joan Sera, and Theresa Mudrock have my enduring gratitude.

Finally, I would like to thank my parents and my family.

Page xii Page 1By the mid-twentieth century, Chicago was a city that drew African American musicians by the thousands from throughout the American South. For many of them, Chicago was an obvious destination. After all, they knew it was a hub for the music industry, and they had purchased their recordings through the Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog, which was published in Chicago. They received news of the city from the Pullman Porters, who spread Chicago's Black-owned newspapers throughout the South and in so doing helped to create an unbreakable link between the rural and the urban African American populations. In addition, Chicago was the home of professional organizations such as the National Association of Negro Musicians, classical-music training was available at the Chicago Conservatory and the University of Chicago, and there were high-quality Black-owned venues such as the Pekin Theater and the city's churches.

All of this was seductive to African American musicians, but none of it changed the fact that Chicago was a city of neighborhoods. This was a polite way of saying that it was a segregated city. The reality of Chicago's pigmentocracy was such that African American musicians were assured membership in the segregated American Federation of Musicians local, and that jobs in the city's symphonies, radio stations, and clubs outside of the black belt were largely off-limits. Therefore, migrating to Chicago meant that they would have to live in a segregated city. For many, living in the city required them to make choices regarding segregation. Some chose to dedicate themselves to undermining the racial system through performances, recordings, and professional organizations. Others sought to create an autonomous cultural sphere that could insulate musicians from the city's racism.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967»

Look at similar books to The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Black Musician and the White City: Race and Music in Chicago, 1900–1967 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.