The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

F OR C ARMILE

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

Until a decade or so ago, I had never set foot in the Great Basin; therefore, I am most grateful to those who introduced me to the region, particularly Kathleen Lubeck of the public information office of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as the Mormon Church is formally known. On her regular visits to New York City, where I was then an editor, she imbued me with the idea that Utah must be a fascinating place to visit. And so it turned out to be. On my first trip to Salt Lake City I met Esther Ruth Truitt Henrichsen, then garden designer for the Mormon Church, whose good-humored slant on Mormon history ignited my enthusiasm for the subject. With Esther as guide, I did Temple Square, visited Brigham Youngs grave site, and toured Gilgal Gardens, a remarkable collection of folk sculpture hidden away in a backyard in central Salt Lake City.

My first visit to Nevadathe Great Basins western half, vastly different from Utah but equally rich in historycame a year or so later, thanks to Henry Wiencek, series editor for the Smithsonian Guide to Historic America, who assigned me to write the volume that included both Nevada and Utah. I owe other trips to the Great Basin to assignments from Carla Davidson of American Heritage magazine and the staff of the now-defunct Americana. On these jaunts, I met and talked with curators, park rangers, professors, archaeologists, librarians, and guides, including the older folks who staff Mormon sites, often retired Latter-day Saints on missions. As I wrote for American Heritage, Anyone who has heard that Mormons are reclusive, suspicious, aggressive, or just plain weird will think otherwise after meeting these gentle and friendly people.

While writing the book, I came to realize that it covered material that I first encountered long ago in college, particularly from the teaching of western historian Frederick Merk and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., whose lectures introduced me to Mormons and other American religious groups. For current research, I was delighted to find that the libraries at Hartwick and SUCO, both colleges in nearby Oneonta, New York, had helpful staffs and large collections of western material. What they did not have I could usually unearth at larger repositories, such as Olin Library at Cornell and the public library in New York City.

I am grateful to my editor, Ray Roberts; his enthusiasm for my original proposal helped sustain me during the dark days of writing ahead. I thank my friend and agent, Maureen Graney, who has stepped in to salvage my adventure in freelance writing on more than one occasion. Jim Zihal of Zihal Design in New York City and photographer Mel Adelglass contributed greatly to the production of the illustrations for the book. Copy editor Patty OConnell earned my gratitude for her fine fine-tuning of the manuscript. And, finally, I want to acknowledge the support, fellowship, and laughs I receive in abundance from my pals in and around Delaware County, New York. (You know who you are.)

I NTRODUCTION

Outside my window a brook brimming with spring runoff rushes downhill. In the valley it joins a stream large enough to have a nameBagleys Brook. This waterway cuts around the village of De Lancey, New York, and soon runs into a real river, the West Branch of the Delaware, which flows through the farmlands of the western Catskills until it is intercepted by a large reservoir. There, part of the water is siphoned off to New York City, but the rest moves on to the Delaware River and then to the sea. To me, this network of brook, stream, and river does just what flowing water is supposed to do: It moves in ever larger increments from headwater to ocean. Even children know that this is the natural order of things, that a stick thrown into a stream will eventually reach the sea.

I have since learned, however, that not all rivers run seaward. In the huge, arid region of the West known as the Great Basin, a brook might start out with vigor down the mountainside but end upto go no fartherin a salty lake. Or, instead of getting ever larger, it might dwindle to a trickle, then disappear entirely in the desert floor. This puzzled early explorers, who did not understand that water evaporated; they could see that three major rivers ran into the Great Salt Lake but could find none running out. Where did the water go? Into a river that they somehow had missed in their explorations? Or did a giant whirlpool suck water through underground passages to the ocean, as some fur trappers believed?

This phenomenon of interior drainage repeats itself throughout the Great Basin. On the north, the regions most important river, the Humboldt, peters out in a marshlike sink. To the west, water pours out of the Sierra Nevada Range into lakes that Mark Twain described as great sheets of water without any visible outlet What they do with their surplus is only known to the Creator. Southern waters also run to the interior and stay, but there the climate is so dry that even a healthy Catskill brook would be considered a major waterway. It is exceptional, this desert basin that drains into itself; there is no other place like it in the United States, and few others in the world.

As a traveler, it took me years to get to the Great Basin. Once there, however, I could understand why the early entrants did not understand its true nature. The region is so vast, so intimidating, and so elemental and different from the rest of the continent that the mind can barely absorb what the eyes see, let alone understand the region as a whole. John Charles Frmont, the famed government explorer, was the first to comprehend the regions unique hydrology and to name it the Great Basin. But the mountain men, who were there before him, and the Mormons, who arrived later, cared little about which way the rivers ran. Simply surviving in an unfriendly climate was job enough.

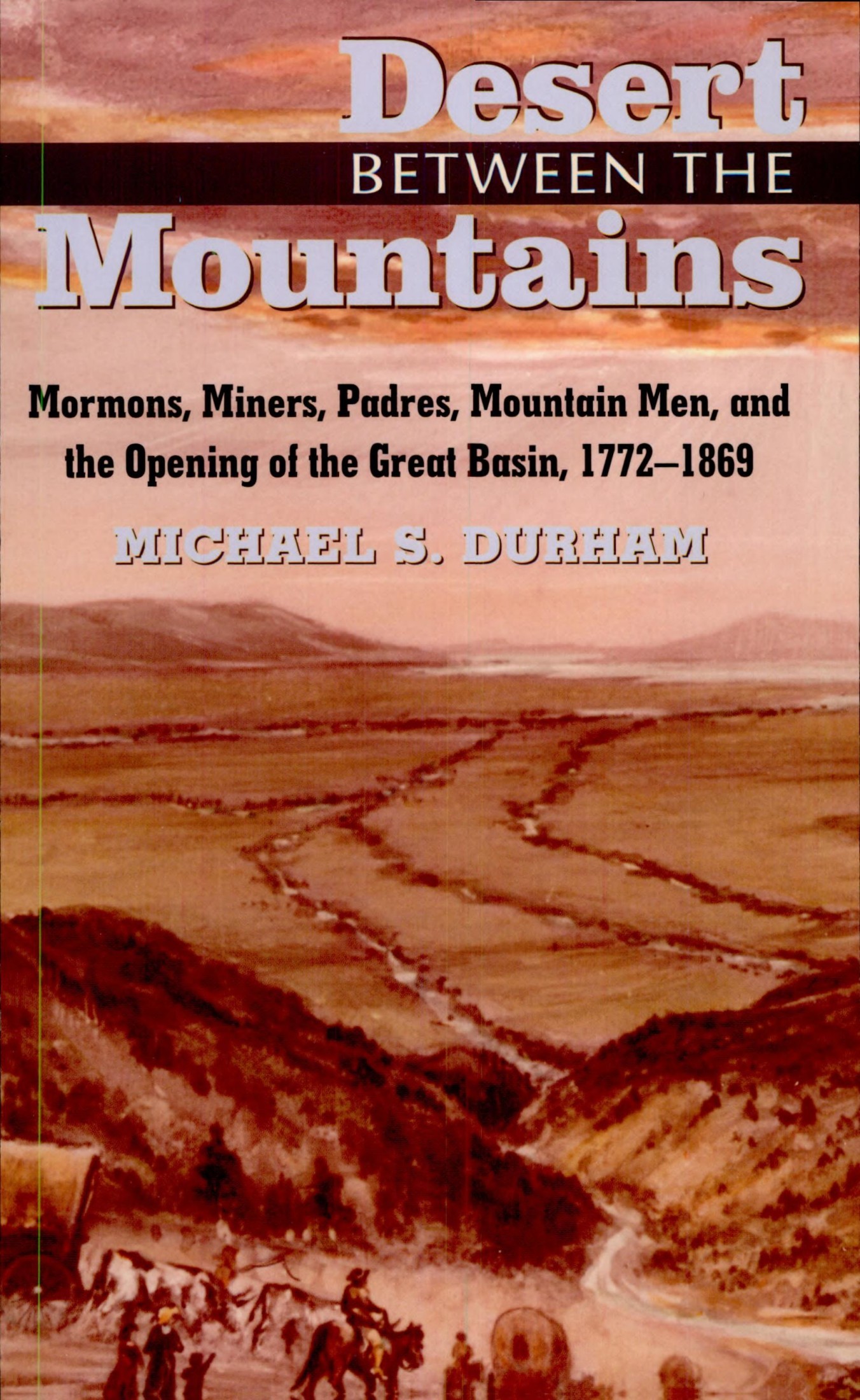

This book is the story of the settlers, travelers, natives, and assorted bit players in the Basin from the entrance of the first Spaniard in 1772 to the coming of the railroad in 1869. It is a story as much about geography and landscape as it is about people and power and money and all the other engines that drive history. The Mormons proudly call themselves a peculiar people. It seems fitting, maybe preordained, that they chose an unusual and peculiar land to be their home.

Now, about that landscape

Part One

FIRST INTO THE GREAT BASIN

Chapter One

A D EAD AND R ICH L AND

The Great Basin is aptly named. It is like a bowl that has been wedged between two mountain rangesthe Sierra Nevada on the west and the Wasatch branch of the Rocky Mountains on the east, although the mid-nineteenth-century explorer James Hervey Simpson saw it as having a triangular shape, nearly that of a right-angled triangle, with the Wasatch Range forming the hypothenuse. As a region, it is vast220,000 square miles. It takes in almost all of Nevada, the half of Utah lying west of the Wasatch, parts of southern Idaho and Oregon, a corner of Wyoming, and a thin slice of eastern California bordering on Nevada. It also reaches into southern California almost to the Pacific Ocean. From north to south, it is nearly 900 miles long at its longest point; east to west, its maximum distance is 570 miles. In all, the Great Basin covers one-fifteenth of the entire country, but, despite its great size, it was 1776, the year of American independence, before any white man made any significant attempt to explore it, and its unique character as a land of interior drainage would not be understood for another three-quarters of a century.