This book was first presented as the Anthony Hecht Lectures in the Humanities given by Daniel Albright at Bard College in 2012. The lectures have been revised for publication.

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Philip Hamilton McMillan of the Class of 1894, Yale College.

Copyright 2014 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Poetry credits can be found in the Poetry Credits at the back of the book.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Fournier type by IDS Infotech, Ltd. Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Albright, Daniel, 1945

Panaesthetics : on the unity and diversity of the arts / Daniel Albright.1st [edition].

pages cm.(The Anthony Hecht lectures in the humanities)

This book was first presented as the Anthony Hecht Lectures in the Humanities given by Daniel Albright at Bard College in 2012. The lectures have been revised for publication.Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18662-8 (alk. paper) 1. Arts. I. Title. NX170.A45 2014

700.1dc23

2013034291

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

Reproduction, including downloading, of the Max Ernst, Wassily Kandinsky, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Saul Steinberg works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Anthony Hecht Lectures in the Humanities, given biennially at Bard College, were established to honor the memory of this preeminent American poet by reflecting his lifelong interest in literature, music, the visual arts, and cultural history. Through his poems, scholarship, and teaching, Anthony Hecht has become recognized as one of the moral voices of his generation, and his works have had a profound effect on contemporary American poetry. The books in this series will keep alive the spirit of his work and life.

To Marta, in the hope that this book will have something of the loveliness of your name

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I WANT TO GIVE MY warmest thanks to Bard College, since this book grows out of the Anthony Hecht lectures I gave there in 2012;

and to Pamela Rosenberg and the American Academy in Berlin, where I resided in Fall 2012the final part of this book was written as I watched the boats gliding out of the mists of the Wannsee like thoughts coming into being;

and to Harvard University, for supporting my research over the years and for providing me with a reliable source of income;

and to my research assistant, Benjamin Ory, and to Suzie Tibor, who helped me find illustrations, and to three people at Yale University Press, Jennifer Banks (whose confidence in this project has sustained me), Heather Gold, and Susan Laity, the most sensitive and esemplastically gifted manuscript editor I've ever known;

I was also fortunate that the superb polymath Simon Morrison read this book and thought along with some of the ideas in it;

and finally I thank my dear friend Marc Shellhe and I have been co-teaching a seminar on Comparative Arts for years, and this book grew out of that seminar. I learned from him much of what I know about Zwischenkunstpanaesthetics

INTRODUCTION

Mousike

Mousike

M USIC . M USIK . M USIQUE . M USICA . M USICA . M.

These words mean the same thing, and pretty well cover Europe and the Western hemisphere. All are derived from , mousikebut this Greek word doesn't mean music. It is related to the word for Muse and means anything pertinent to the Muses; therefore it includes not only music but dance, mime, epic poetry, lyric poetry, history, comedy, tragedy, even astronomy. In Roman times the nine Muses were parceled out fairly neatly among these nine arts, one Muse to one art. But earlier, the boundaries of the areas overseen by each Muse were unclear and overlapping. Greek mythologizing tended to confuse and unify the arts: an artistic medium was not a distinct thing but a kind of proclivity within the general domain of Art.

On the other hand, the founding text of academic study of the interrelations among the arts is Aristotle's Poetics, a book with a strong appetite for division. Aristotle isolates six distinct aspects of dramatic art: plot (mythos), character (ethe), thought (dianoia), diction (lexis), spectacle (opsis), and music (melos). Far from blurring these categories, Aristotle ranks them in value, with plot as the most important, music much less so, and spectacle least of all. For Aristotle, it seems that verbal art takes precedence over all othersand indeed the visual arts seem so ancillary in Greek culture that neither painting nor sculpture is dignified with a Muse of its own.

And yet the Poetics does not exalt the literary as much as it seems to. Nowadays we hear the word plot and may think of a verbal summary of a story; but for Aristotle the plot is as much a matter of bodies moving on a stage as a matter of words. In Greek thought, verbal art spills out of the purely textual in all directions: into mime, into chant, into elocution. The very word poetics refers to making, not to any specifically verbal craft: we might speak of the poetics of a sonnet, and we might speak of the poetics of a sofa.

The purpose of this book is to provide an introduction to the study of the comparative arts. And the proper place to begin is with the fundamental question of comparative arts: Are the arts one, or are they many? This question vexed the Greeks, and continues to vex us today.This German painter and novelist, himself extremely versatile, resolutely states an intuition common throughout the centuries.

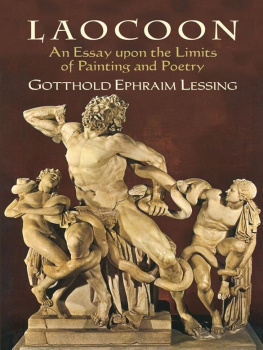

Strong assertions of the essential disunity of the arts are hard to find before early modern times. But the discipline of comparative arts arises from the work of just such a divider, Gotthold Lessing, who argued in Laokoon (1766) that the temporal arts, such as music and literature, had protocols wholly distinct from those of the spatial arts, such as sculpture and painting. He began by asking himself a question that the great art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann had asked before him: In the famous Roman statue (excavated in Michelangelo's time), why isn't Laocon screaming? Laocon and his children are being squeezed to death by an enormous snake; but Laocon's mouth is a tight stoic line. Lessing argued that artworks in a sequential medium pertain to action and should be loud, vigorous, expressive, so it's appropriate that in the Aeneid Virgil depicts Laocon as raising a horrible clamor to the stars; but artworks in a spatial medium pertain to stasis and should be decorous, calm, poised, so it's right that a statue should strive for balance and beauty even if it depicts a man dying horribly. A work of visual art is an immobile noun, or a collection of immobile nouns; a poem, a novel, a piece of music is all verb. In this way the arts diversify, even show a certain hostility to one another. Others who agreed with Lessing include Irving Babbitt, Clement Greenberg, Theodor Adorno, and the Victorian critic W. J. Courthope, who defined decadence in art as a quest for originality achieved when one of the arts borrows some principle from another. A famous example of a medial separatist is Marshall McLuhan, who thought that the medium was the message; for an extreme unifier, such as Wassily Kandinsky, the medium, far from being the message, is pretty much irrelevant to it.

Next page

Mousike

Mousike