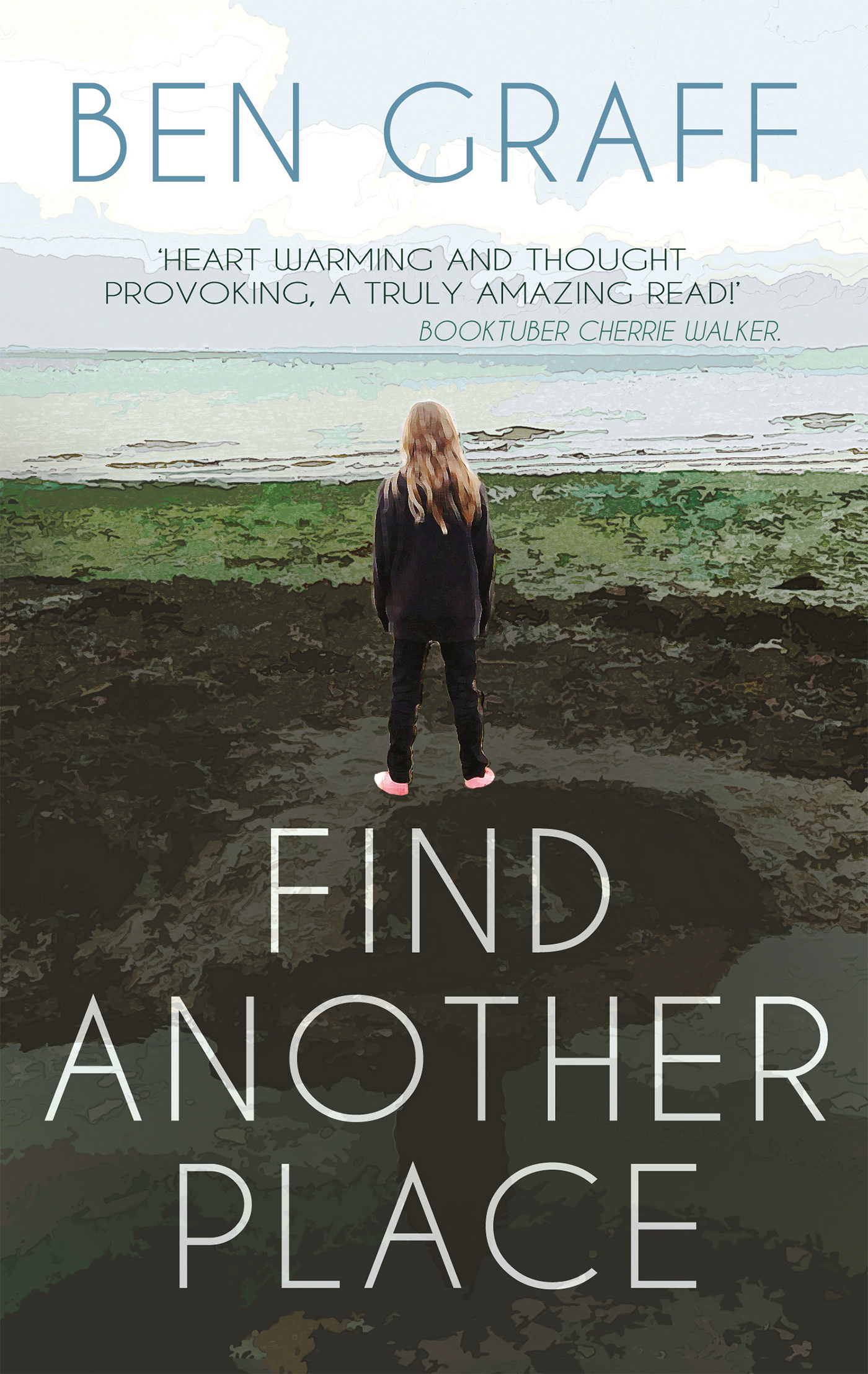

Heart Warming and thought provoking a truly amazing read! I adored this book! I laughed, I cried, I nodded my head in agreement, as someone who has not only lost a parent, has a parent with MS and is a parent myself I could relate to this book on so many different levels and it will stay with me for years to come.

Cherrie Walker Booktuber.

Family man Ben Graff knows that life is like a chess game, punctuated with triumphs and disasters and a constant search for the truth. He understands that the purpose of life must be to have a life of purpose and we are all but chess pieces in the magnificent game of life.

This is the brave and honest account of a man who lives his life as he plays his beloved chess. Always curious and intelligent, simple and yet complex. Graff drew me into his world of discovery from the first page and taught me that without hope you cannot start the day A quite remarkable story.

Carl Portman Chess Behind Bars

A well written, thoughtful family memoir, which anyone with a family can relate to.

Kate Jones Bookbag

Ben Graff was born in Aldershot in 1975.

He read law at Bristol University.

Find Another Place is his first book.

Find

Another Place

Ben Graff

Copyright 2018 Ben Graff

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email: books@troubador.co.uk

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1789010 442

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

For all of them

The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.

L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between , 1953

Do not ask your children to strive for extraordinary lives. Such striving may seem admirable, but it is the way of foolishness. Help them instead to find the wonder and the marvel of an ordinary life. Show them the joy of tasting tomatoes, apples and pears. Show them how to cry when pets and people die. Show them the infinite pleasure in the touch of a hand. And make the ordinary come alive for them. The extraordinary will take care of itself.

William Martin, The Parents Tao te Ching: Ancient Advice for Modern Parents , 1999

In my youth I was determined to become a writer. I tried to write stories about spies and criminals, a world of which I had no experience. Little did I realise that the family I have just described provided the material for any number of novels. By the time I did realise it, it was too late.

Holmes Family History As remembered by Martin Holmes, 2000

Dear Girls (special)

11/11/04

Just a few bits & pieces for you both. The velvet trousers will look adorable on you, Annabelle, & the pink outfit is for you, Madeleine. Give my love to Mum and Dad. Will be seeing you all at Xmas. Until then, kiss, kiss, kiss.

Grandma Theresa

Contents

Foreword

F amilies are their stories, said my grandfather Martin that late autumn day in 2001, as he placed a clear plastic folder containing his journal into my hands. His fingers felt cold on mine as they brushed briefly, the copper wrist bracelet he wore to help with his arthritis seeming to hang a little more loosely than before. The remaining hair on his head was the same natural black it had always been, the grey moustache neatly trimmed as ever, but he walked cautiously and weighed his words carefully, just as the writer he had always wanted to be might have done. He both was and was not quite the way I remembered him.

In the summer you would be able to hear the shouts of children playing at the sailing school across the creek, but they were long gone now, and other than the clank of the car ferry unloading, no sounds carried across the water. Over the years, I had spent many hours watching from the shingle of Fishbourne beach, and from the deck of family boats, as the ferries went about their work. I had crossed this stretch of water at the beginning and end of family holidays, and listened to their low rumble in the quiet of the night, which was still just audible even from Martins house in Ryde.

We stood alone and it would be years before I saw that this moment too was also part of a story that could be re-told, made sense of or not, that had meant something once and might do so again. He had nodded proprietorially and told me that his story was complete and, if older and wiser, I might have seen something almost mystical, sacred even, in that moment, but I was not and I did not.

Now as I write this in 2017, his use of the word complete is what I think to most, and I can see that day again when we stood together outside the Fishbourne Inn on the Isle of Wight, with a breeze from the Solent gently blowing dying leaves off the trees and into the mud of the near-empty beer garden. There were no other patrons outside, nor any sign that there had been any. No beer that had been reduced to a layer of foam in lipstick-marked glasses, no cigarettes smouldering to nothing in abandoned ashtrays, no nearly empty plates yet to be removed by the waiting staff. After eating we had only come outside to get some air, and the meal had not been a complete success. He seemed distracted, perhaps thinking to what he was going to share, but it might have been that he was tired. I had lost at chess the previous night and kept drifting back to why I had pushed the pawn when playing the knight would have been so much better, unable to separate myself fully from the disappointment. He had fiddled nervously with the folder while we ate, but he did not mention it until now, when he handed me his story.

I did not ask whether he meant to say his journal was complete, or if he thought something more fundamental was drawing to a close. Perhaps I already knew. He had finished his writing and his life as good as, while at twenty-four my own was only just beginning to inch toward any form of definition, and my writing would not have overly employed whoever had printed and wrapped in plastic the copies of his journal.

I had met Katharine and she was pregnant, but we were closer to being married and further away from being parents than we thought. I was two years into a job that I did not much like but feared to leave, while Martins much more protracted career was long since over. Instead of the novelist he had wanted to be, he had spent his working life running shops that sold clothes, then shoes, finally musical instruments; I would later find that the other commercial ventures that were meant to give him a way out were described in his writing as disastrous and best forgotten. My own career had been mainly spent writing policy papers for a large organisation, which generally liked the way they were written, though the pieces were always wrong as somebody more senior either already had, or had not yet, decided what the answer was meant to be. In contrast, Martins journal was much more substantive, a last piece of work, a final project. As a matter of chronology, everything else he had done had led up to its creation.