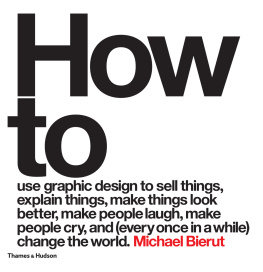

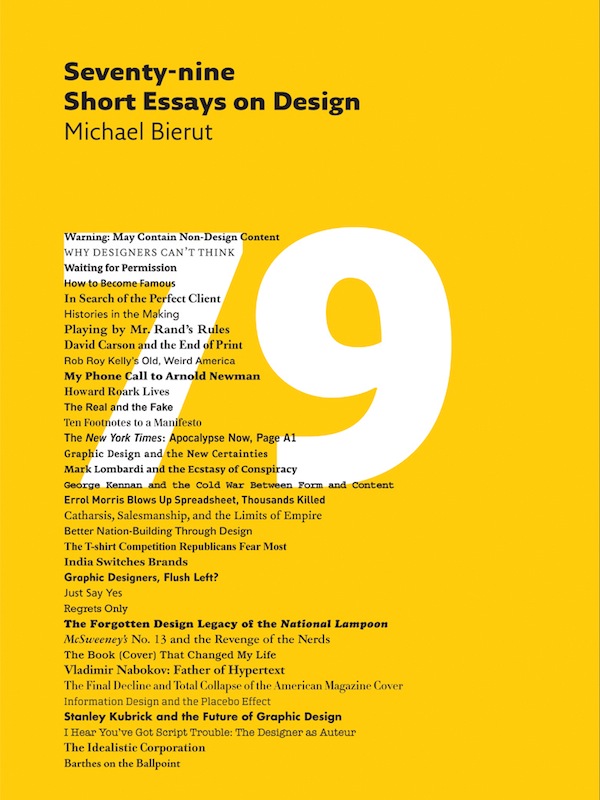

Seventy-nine

Short Essays on Design

Michael Bierut

Princeton Architectural Press

New York

Published by Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657.

Visit our web site at www.papress.com.

2007 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

Printed and bound in China

10 09 08 07 4 3 2 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editor: Lauren Nelson Packard

Designer print edition: Abbott Miller, Pentagram

Special thanks to: Nettie Aljian, Sara Bader, Dorothy Ball, Nicola Bednarek, Janet Behning, Becca Casbon, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Pete Fitzpatrick, Wendy Fuller, Sara Hart, Jan Haux, Clare Jacobson, John King, Mark Lamster, Nancy Eklund Later, Linda Lee, Katharine Myers, Scott Tennent, Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton Architectural Press

Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bierut, Michael.

Seventy-nine short essays on design / Michael Bierut.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56898-699-9 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61689-071-1 (digital)

1. Commercial artUnited StatesHistory20th century. 2. Graphic artsUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title. II. Title: 79 short essays on design.

NC998.5.A1B52 2007

741.6dc22

2006101224

Art should be like a good game of baseballnon-monumental, democratic and humble. With no hits, no runs, and no errors at the bottom of the ninth, we know something historical is happening. Good art leaves no residue.

Siah Armajani, 1985

The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter.

Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) to Wilmer Cook (Elijah Cook, Jr.) in The Maltese Falcon , screenplay by John Huston from the novel by Dashiell Hammett, 1941

Preface

I consider myself a designer, not a writer.

Over ten years ago, on the basis of very little evidence, three brilliant editors each began giving me modest writing assignments: Steve Heller, Chee Pearlman, and Rick Poynor.Their encouragement and advice taught me how to begin to think as a writer. About four years ago, Rick, Bill Drenttel, Jessica Helfand, and I decided, without any particular game plan, to create a blog. This book is largely the product of that decision, and of that friendship. I go to work every day to be inspired and stimulated by the best designers in the world: Jim Biber, Michael Gericke, Luke Hayman, Abbott Miller, Lisa Strausfeld, and especially Paula Scher, whose own writing was an important model for me. Abbott created the elegant (and funny) design for this book. Sash Fernando heroically saw the design through to completion. I am grateful to all of them. At Princeton Architectural Press, I thank Kevin Lippert, Mark Lamster, Clare Jacobson, and Lauren Nelson Packard; they suggested this book and actually made it happen.

Finally, I send my love and thanks to Dorothy, Elizabeth, Drew, and Martha Marie.

Writing about design has been a valuable way for me to understand the work I do. I hope that reading about design provides some value to others.

Warning: May Contain Non-Design Content

I write for a blog called Design Observer . Usually my co-editors and I write about design. Sometimes, we dont. Sometimes, for instance, we write about politics. Whenever this happens, in come the comments: What does this have to do with design? If you have a political agenda please keep it to other pages. I am not sure of your leaning but I come here for design.

I come here for design. It happens every time the subject strays beyond fonts and layout software. (Obscure references... trying to impress each other... please, can we start talking some sense?) In these cases, our visitors react like diners who just got served penne alla vodka in a Mexican restaurant: its not the kind of dish they came for, and they doubt the proprietors have the expertise required to serve it up.

Guys, I know how you feel. I used to feel the same way.

More than twenty years ago, I served on a committee that had been formed to explore the possibilities of setting up a New York chapter of the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA). Almost all of the other committee members were older, well-knownand, in some cases, legendarydesigners. I was there to be a worker bee.

I had only been in New York for a year or so. Back in design school in 1970s Cincinnati, I had been starved for design. It would be hard for a student today to imagine a world so isolated. No email, no blogs. Only one (fairly inaccessible) design conference that no one I knew had ever attended. Because there were no AIGA chapters, there were no AIGA student groups. Few of us could afford subscriptions to the only design magazines I knew about, CA , Print , and Graphis . Those few copies we got our hands on were passed around with the fervor of girlie magazines after lights-out at a Boy Scout jamboree. No How , no Step , and of course no Emigre or dot dot dot . We studied the theory of graphic design day in and day out, but the real practice of graphic design was something mysterious that happened somewhere else. It wasnt even a subject for the history books: Phil Meggs wouldnt publish his monumental History of Graphic Design until 1983.

In New York, I was suddenly inwhat seemed to me then, at leastthe center of the design universe. There was already so much to see and do, but I wanted more. I was ravenous. Establishing a New York chapter for the AIGA would mean more lectures, more events, more graphic design. For the committees first meeting, I had made a list of all designers I would love to see speak, and I volunteered to share it with the group.

A few names in, one of the well-known designers in the group cut me off with a bored wave. Oh God, not more show-and-tell portfolio crap. To my surprise, the others began nodding in agreement. Yeah, instead of wallowing in graphic design stuff, we should have something like...a Betty Boop film festival. A Betty Boop film festival? I wanted to hear a lecture from Josef Mller-Brockmann, not watch cartoons. I assumed my senior committee members were pretentious and jaded, considering themselvesbizarrelytoo sophisticated to admit they cared about the one thing I cared about most: design. I was confused and crestfallen. Please, I wanted to say, can we start talking some sense?

I thought I was a pretty darned good designer back then. A few years before, in my senior year, I had designed something I was still quite proud of: a catalog for Cincinnatis Contemporary Arts Center on the work of visionary theater designer Robert Wilson. The CAC didnt hire me because I knew anything about Robert Wilson. I had never heard of him. More likely they liked my price: $1,000, all in, for a 112-page book, cheap even by 1980 standards.

The CAC s director, Robert Stearns, invited me to his house one evening to see the material that needed to be included in the catalog: about 75 photographs, captions, and a major essay by the New York Times critic John Rockwell. I had never heard of John Rockwell. To get us in the mood, Stearns put on some music that he said had been composed by Wilsons latest collaborator. It was called Einstein on the Beach and it was weird and repetitive. The composer was Philip Glass. I had never heard of Einstein on the Beach or Philip Glass. Stearns gave me the album cover to look at. I noticed with almost tearful relief that it had been designed by Milton Glaser. I had heard of Milton Glaser.