CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Adlestrop Yes. I remember Adlestrop The name, because one afternoon Of heat, the express-train drew up there Unwontedly. It was late June. The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat. No one left and no one came On the bare platform.

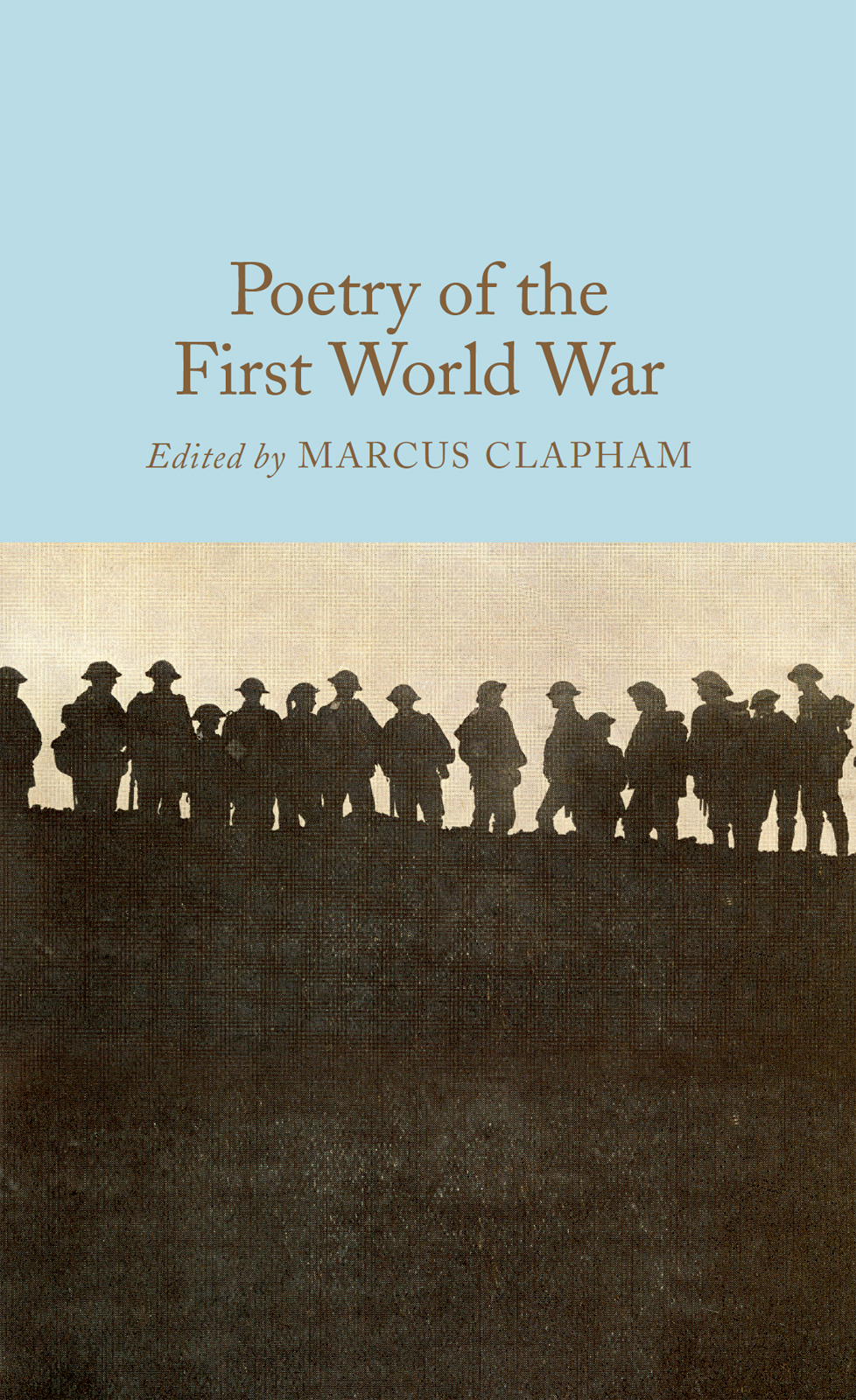

What I saw Was Adlestroponly the name And willows, willow-herb, and grass, And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry, No whit less still and lonely fair Than the high cloudlets in the sky. And for that minute a blackbird sang Close by, and round him, mistier, Farther and farther, all the birds Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire This poem describes an incident in Edward Thomass journey to Dymock on 24th June 1914, four days before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo, which set in train the events which led to the outbreak of what came to be known as The Great War. Written in January 1915 before Thomas enlisted, it seems to encapsulate the prelapsarian ideal of the endless Edwardian summer. It was for this ideal that young men answered Lord Kitcheners Your Country Needs You by volunteering for the New Armies in tens of thousand for an adventure that was widely thought would be over by Christmas. They lost their illusions in the gas at Loos and on the uncut barbed wire of the Somme. The poetry of the First World War is remarkable in its endurance, its quantity and above all its power to animate an episode in human history we should never allow ourselves to forget.

It is strange that poetry written in such appalling conditions a hundred years ago should still have the ability to move its readers and those who hear it read. It produces in the reader or hearer an astonished pity for the waste of men and the suffering that they endured in the first protracted industrialised conflict since the American Civil War fifty years previously. In the much-quoted phrase from Wilfred Owens Preface My subject is War and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity. He goes on to say Yet these elegies are to this generation in no sense consolatory. They may be to the next.

All a poet can do today is warn. That is why the true Poets must be truthful. His poems are, to some extent, consolatory to succeeding generations, but the warning is perhaps even stronger. There are nearly seventy poets in this anthology, and they represent only a very small proportion of those who wrote about the war. Poets whose subject was war came from all backgrounds, because the great Victorian educational reforms had produced a remarkably literate population and, in an age when the cinema was in its infancy, entertainment consisted largely of reading and music. Recitations at home, in public houses and music halls were immensely popular, and the balladic rhythms of poets such as Rudyard Kipling, Robert W.

Service, George Leybourne, Albert Chevalier and J. Milton Hayes were well known. The anonymous pieces at the beginning of the book give a small indication of the sardonic parodies that combine church and music hall antecedents, and date from the middle of the war. In its early days, a romantic optimism informed the patriotic verse of 1914: Now God be thanked wrote the golden-haired Rupert Brooke Who hath matched us with His hour And caught our youth, and wakened us from sleeping. For many, the Edwardian and early Georgian eras were ones of tawdry values in which scandal and hypocrisy in public life abounded, and labour unrest, Suffragettes and Irish Home Rule dominated domestic politics. Popular perception of warfare envisaged a war of movement, of cavalry charges and horse artillery, founded largely on memories of the Second Boer War.

As far as war in Europe was concerned, longer memories harked back to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 which was over in a matter of months. When war broke out in August 1914, the generally accepted view in Britain was that it would be over quickly. Thousands of young men of all classes enlisted at once, keen to escape the ennui of their workaday lives, and see some action before the war ended. Hindsight is wonderfully clear, and it is easy to see the unfolding of events following the assassination of Franz Ferdinand as a Greek tragedy. The Austrians declared war on Serbia, the Russians mobilised in support of Serbia, the Germans mobilised in support of Austria, the French mobilised in support of Russia and Great Britain and its Empire mobilised when the Germans invaded Belgium. The famous Schlieffen Plan, which might have ended the war by Christmas, was so adapted by German caution that Joffre, with some help from the British Expeditionary Force, was able to halt the German advance.

Then followed the sportily named race for the sea in which opposing forces dug trench fortifications from the North Sea to the Swiss border. It was these trenches that inspired most of the poems in this book. Trench life was hellish for all sides, especially for the British (though the French army endured its own Calvary of Verdun). They held the line from near the Belgian coast in the north to the Somme in the south. Along the whole line the Germans tended to hold the high ground. Not only that, but the incessant use of high-explosive shells destroyed the drainage system of the Flemish Plain so that British trenches were frequently waterlogged, giving rise to many health problems, and it was little better further south in Picardy.

The German imperative in this stalemate was not to be defeated, while the Allies prime concern was to win and recapture lost territories, entailing what was effectively siege warfare. Although heavy artillery bombardment was the main attacking arm, when it had done what work it could against enemy batteries, machine-gun nests, pill-boxes and barbed wire, it was the front-line soldier who had to try to occupy enemy territory. This exposed him to death by rifle fire, mortar fire, machine-gun fire, gas, and the possibility of obliteration or dismemberment from a direct hit by a shell. If he reached the enemy front line, hand-grenades, side-arms and bayonets still awaited him. Merely occupying the front line was fraught with danger from artillery and mortar shells which could bury dozens, from snipers and from health hazards such as trench fever, which was caused by the ubiquitous lice and nits, and trench foot caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to damp, unsanitary and cold conditions, which were common in the flooded trenches. In the early stages of the war, having trench foot was a punishable offence, as was venereal disease throughout the war; there were many ludicrous regulations that had to be borne as well see Wilfred Owens Inspection and officially the upper lip might not be shaved.

With the arrival of Kitcheners New Armies, which contained young men who were incapable of growing moustaches, this regulation was abolished by an Army Order dated 6 October 1916 issued by Lieutenant-General Sir Nevil Macready, Adjutant-General to the Forces (who loathed his own moustache and immediately shaved it off). Even out of the line, in support, in reserve or resting, soldiers were not necessarily safe from enemy action, and the din of gunfire was always with them. In or out of the line, soldiers lived in a mad and terrible world of their own. The desolation and ruin of the country in which they fought was almost unimaginable. (Perhaps the two most telling descriptions are by novelists who never fought in the trenches. The end of Evelyn Waughs Vile Bodies has a description of a ruined battlefield that is memorably ghastly, and Sebastian Faulkss Birdsong sustains the banal horror of everyday life in and below the trench systems.) The daily routine of life at the front was a mixture of squalor and boredom, punctuated by moments of terror.