You certainly think right when you think Boston people are mad. The frenzy was not higher when they banished my pious great grandmother, when they hanged the Quakers andthe poor innocent witches, than the political frenzy has been for a twelve-month past.

This is a work of nonfiction. All quotations are from the historical record, largely from the lengthy transcripts of the four days in 1637 and 1638 when Anne Hutchinson was brought to trial before the Great and General Court of Massachusetts and then the First Church of Boston. In citing these transcripts I have for the sake of clarity modernized spelling and added punctuation and occasionally emphasis. In quoting the Bible, I use the King James Version except when the quotation is in the words of a seventeenth-century speaker. In those cases the translation is from the Geneva Bible, which Anne Hutchinson and her Puritan contemporaries used.

All sources for the book are listed in the bibliography. All dates are from the historical record, which in the seventeenth-century English world was based on the Julian calendar, created in 45 BCE by Julius Caesar, rather than on the modern Gregorian calendar, created by Pope Gregory in the late sixteenth century. England and its colonies maintained the old calendar (and its use of March 25 rather than January 1 as the start of a new year) until 1752 as a way of avoiding the innovations of a pope. To modernize any seventeenth-century date in the book, simply add eleven days to it.

I have sought the assistance and advice of many historians, other scholars, curators, and preservationists, who are named in the acknowledgments. If despite all their help the text contains any errors of fact, the responsibility is mine.

But history, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in. The quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all.

J ANE A USTEN

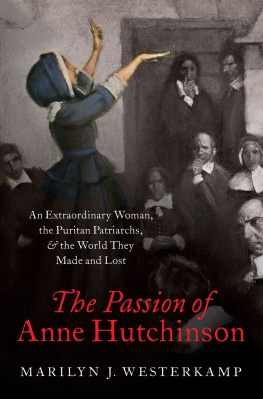

One warm Saturday morning in March, as I let my children out of our minivan alongside a small road in rural Rhode Island, a part of America wed never visited before, a white pickup truck rolled to a stop beside us. Leaving my baby buckled in his car seat, I turned to the trucks driver, a middle-aged man with gray hair. This is where Rhode Island was founded, you know, he said to me. Right here. This is where Anne Hutchinson came.

And you know what? the friendly stranger added, warming to his subject. A lady came here all the way from Utah last summer, and she was a descendant of Anne Hutchinsons.

For a moment I wondered how to reply. See those girls there? I said, pointing at my three daughters, who watched us from a grassy spot beside the dirt road. Theyre Anne Hutchinsons descendants too.

In fact, I had driven my children from Boston to Portsmouth, Rhode Island, to explore the place that their eleventh great-grandmother, expelled from Massachusetts for heresy, had settled in 1638.

Anne Hutchinson is a local hero to the man in the pickup, but most Americans know little about her save her name and the skeleton of her story. To be sure, Hutchinson merits a mention in every textbook of American history. A major highway outside New York City, the Hutchinson River Parkway, bears her name. And a bronze statue of her stands in front of the Massachusetts State House near that of President John F. Kennedy. Yet Hutchinson herself has never been widely understood or her achievements appreciated and recognized.

In a world without religious freedom, civil rights, or free speechthe colonial world of the 1630s that was the seed of the modern United StatesAnne Hutchinson was an American visionary, pioneer, and explorer who epitomized the religious freedom and tolerance that are essential to the nations character. From the first half of the seventeenth century, when she sailed with her husband and their eleven children to Massachusetts Bay Colony, until at least the mid-nineteenth century, when Susan B. Anthony and others campaigned for female suffrage, no woman has left as strong an impression on politics in America as Anne Hutchinson. In a time when no woman could vote, teach outside the home, or hold public office, she had the intellect, courage, and will to challenge the judges and ministers who founded and ran Massachusetts. Threatened by her radical theology and her formidable political power, these men brought her to trial for heresy, banished her from the colony, and excommunicated her from the Puritan church. Undeterred, she cofounded a new American colony (her Rhode Island and Roger Williamss Providence Plantation later joined as the Colony of Rhode Island), becoming the only woman ever to do so. Unlike many prominent women in American politics, such as Abigail Adams and Eleanor Roosevelt, Hutchinson did not acquire power because of her husband. She was strong in her own right, not the wife of someone stronger, which may have been one reason she had to be expunged.

Anne Hutchinson is a compelling biographical subject because of her personal complexity, the many tensions in her life, and the widespread uncertainty about the details of her career. But there is more to her story. Because early New England was a microcosm of the modern Western world, the issues Anne Hutchinson raisedgender equality, civil rights, the nature and evidence of salvation, freedom of conscience, and the right to free speechremain relevant to the American people four centuries later. Hutchinsons bold engagement in religious, political, and moral conflict early in our history helped to shape how American women see ourselves todayin marriages, in communities, and in the larger society.

Besides being a feminist icon, Hutchinson embodied a peculiarly American certainty about the distinction between right and wrong, good and evila certainty shared by the colonial leaders who sent her away. Cast out by men who themselves had been outcasts in their native England, Hutchinson is a classic rebels rebel, revealing how quickly outsiders can become authoritarians. The members of the Massachusetts Court removed Anne because her moral certitude was too much like their own. Her views were a mirror for their rigidity. It is ironic, the historian Oscar Handlin noted, that the Puritans had themselves been rebels in order to put into practice their ideas of a new society. But to do so they had to restrain the rebellion of others.

Until now, views of Anne Hutchinson in American history and letters have been polarized, tending either toward disdain or exaltation. The exaltation comes from womens clubs, genealogical associations, and twentieth-century feminists who honor her as Americas first feminist, career woman, and equal marital partner. Yet the public praise is often muted by a wish to domesticate Hutchinson. The bronze statue in Boston, for instance, portrays her as a pious mothera little girl at her side and her eyes raised in supplication to heavenrather than as a powerful figure standing in the Massachusetts General Court, alone before men and God.

Her detractors, starting with her neighbor John Winthrop, first governor of Massachusetts, derided her as the instrument of Satan, the new Eve, and the enemy of the chosen people. In summing her up, Winthrop called her this American Jezebel the emphasis is hismaking an epithet of the name that any Puritan would recognize as belonging to the most evil and shameful woman in the Bible. Hutchinson haunted Nathaniel Hawthorne, who used her as a model for Hester Prynne, the adulterous heroine of The Scarlet Letter. Early in this 1850 novel, Hutchinson appears at the door of the Boston prison.