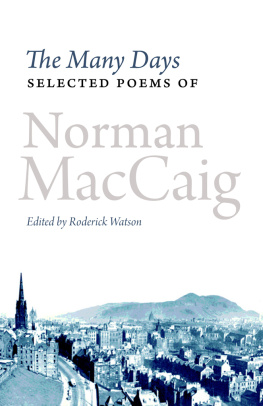

The Many Days

This ebook edition published in 2013 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk First published in Great Britain in 2010

by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

Revised edition published 2013 Poems copyright the estate of Norman MacCaig

Introduction copyright Roderick Watson, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-780-6

Print ISBN: 978-1-84697-171-6 Version 1.0 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Introduction

His poems are discovered in flight, migratory, wheeling and calling. Everything is in a state of restless becoming: once his attention lights on a subject, it immediately grows lambent. In this description, Seamus Heaney gets to the heart of Norman MacCaigs verse. Time and again MacCaig brings us to a moment of evanescent delight, to a humane epiphany of love and mortality in that good place we know as the world around us, but hardly ever

see so clearly.

MacCaigs clear-sightedness is almost a matter of creative moral duty (one thinks of him as a conscientious objector during the Second World War). His imagination, in turn, allows us to see the world afresh, newly minted with surprise and delight: a goat with amber dumb-bells in his eyes, or that cow bringing its belly home, slung from a pole, or the thorn bush that traps stars in an encyclopaedia of angles. MacCaigs metaphors are well known and loved by the thousands of readers and listeners who enjoy his work. In poem after poem he leads us to make the leap that will reveal the connection, but also the disconnection, between the metaphor and the thing itself. The poet is always aware of the gap, sometimes ironically, often humorously, and sometimes as an artist in despair of ever really bridging it. Thus there are darker and more personal poems in this selection that speak of moments like the ragged man waiting for him in the poem Bright day, dark centre, or the need to feel the world like a straitjacket in On the pier at Kinlochbervie, where the strain of the poems opening metaphor about a bluetit the size of the world pecking the stars out one by one speaks for a moment of personal terror by turning one of his fond and familiar creative leaps into something simultaneously ludicrous and menacing.

Such dichotomies are never far from the surface in MacCaig, and yet the landscape he shows us in his work, like the peaceable kingdom of animals and people and mountains that he found in Assynt, is everywhere, finally, infused with a caring attention. Seamus Heaney sees a link with early Irish verse and the Scottish Gaelic tradition in the clarity of image, the sensation of blinking awake in a pristine world, the unpathetic nature of nature in his work, and MacCaig specifically invoked that tradition with the praise poems he wrote for a road, a collie, a boat, a thorn bush humble subjects, so radiantly realised. The collective achievement of MacCaigs lyrics is unprecedented in modern poetry. I cannot think of any other poet anywhere who has so faithfully and so persistently explored the act of noticing, and the nature of being in the world, through the thousands of epiphanic moments that are his poems, in a creative career of sixteen collections and more than fifty years. Such stern commitment to a single craft, and such generous devotion to the illumination of the world, has an almost monk-like quality to it, although MacCaig no lover of organised religion would have hated the comparison. But if you think of it as a secular devotion, and remember the strange little monsters to be found in the margins of the pages of the Book of Kells, then perhaps the analogy will hold.

It has not been easy to make a selection from the treasure house of the complete poems. I was helped in this task and owe a debt of thanks to Tom Pow, Alan Taylor and Ewen McCaig. Our meetings were lively as we tried to strike a balance between representing the much-loved poems that any reader would expect to find in a selected MacCaig, and choosing less familiar verses. The titled sections in this book are my way of perhaps providing new contexts for even the most well-known verses, and for allowing MacCaigs own lines to reveal common themes and preoccupations in his work. Thus each section starts with a title poem that sets the scene for the selection to follow: Among Scholars, for example, introduces a series of poems that revolve around MacCaigs regular sojourns in Achmelvich and the west of Scotland, while the poems in From My Window speak of his time in cities and most especially in Edinburgh. The section entitled Old Maps and New reminds us that MacCaig has often reflected directly and indirectly on Scottish history, not least in his long poem A Man In Assynt, whose personal-political focus must be included in any proper account of his work.

The verses in Likenesses reflect sometimes self-critically on the poets own penchant for metaphor and have insights to offer on the nature of the creative process itself. Under Ineducable Me we find poems of a more personal aspect, humorous and sometimes disturbingly painful, from a writer who had nothing but contempt and distrust for gush and the so-called confessional poetry of the 1960s. The poems of One of the Many Days bring us to the Edenic world of creatures and landscapes that is the setting for some of Normans most popular lyrics, just as those in Balances remind us that the human world has a darker side to it that no poet can escape or ignore. And if the prevailing spirit of MacCaigs achievement is still one of surprise and delight, then the reflections on death and personal loss from In That Other World remind us that intimations of mortality underlie the beauty of all existence, and have powered the heart of every fine lyric that has ever been written. But in the end for MacCaig, and not just for the poems that make up the final section, A Man in My Position, the first and the last word, clear-eyed, sardonic or tender, has always been love. But no editorial categorisation can ever do justice to the way MacCaigs themes interpenetrate each other with surprise, humour, terror and delight at every turn of every line.

Nor are these sections meant to suggest otherwise; rather they are a way of encouraging MacCaigs own poems to speak for themselves and (in this arrangement) among themselves, to set up the best kind of creative dialogue, section to section, poem to poem. Everything speaks to everything else in MacCaigs work and, despite those wonderful frogs, he never wrote simply an animal poem in his life. Roderick Watson

Ineducable Me

Ineducable me I dont learn much, Im a man of no improvements. My nose still snuffs the air in an amateurish way. My profoundest ideas were once toys on the floor, I love them, Ive licked most of the paint off. A whisky glass is a rattle I dont shake.

When I love a person, a place, an object, I dont see what there is to argue about. I learned words, I learned words: but half of them died for lack of exercise. And the ones I use often look at me with a look that whispers, Liar. How I admire the eider duck that dives with a neat loop and no splash and the gannet that suddenly harpoons the sea. Im a guillemot that still dives in the first way it thought of: poke your head under and fly down. Climbing Suilven I nod and nod to my own shadow and thrust A mountain down and down.

This ebook edition published in 2013 by

This ebook edition published in 2013 by