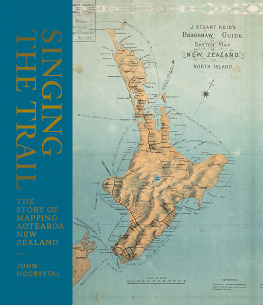

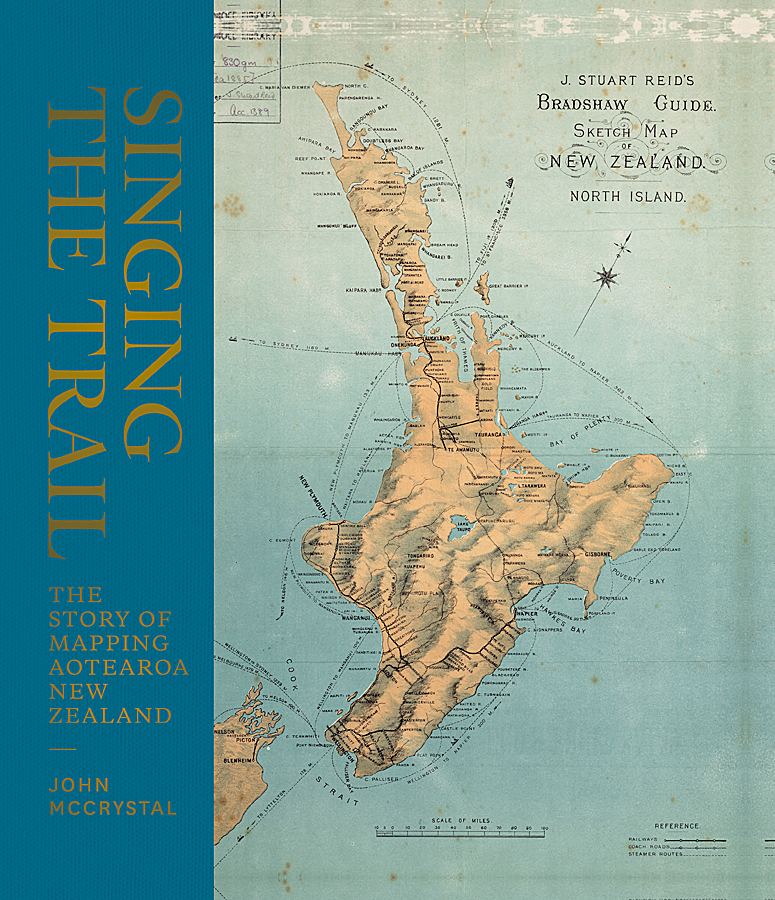

THE STORY OF MAPPING AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

The very first maps, oral maps made by early Polynesian and Mori settlers, were waypoints, lists of places in songs, chants, karakia and stories that showed direction.

Hundreds of years later, Abel Tasman made the first attempt at a physical map; followed more than a century later by James Cook, whose more detailed map was made as he circumnavigated Aotearoa. Once the detail of the coastline was filled in, it was the turn of the surveyors, explorers, rockhounds, gold diggers and politicians to negotiate the internal detail.

The story of these maps is also the story of Aotearoa New Zealand.

DISCLAIMER

Due to limitations of ebook files, the finer details of some maps in this ebook are not entirely clear.

INTRODUCTION

M aps mean different things to different people. For me, they have meant a range of things, according to the various stages of my life.

When I was a child, my brothers and I used to explore our neighbourhoodthe playing fields, the stinky creek, the big subdivision, the boundaries of the farmlet from which the subdivision had been carved. We named significant features: a glade where the foetid water of the creek pooled we named Minty Pools after our dog, a constant companion on our voyages of exploration; the clay hills of the subdivision we named the clay hills (James Cook, ever the prosaic namer, would have nodded in approval at that one); a thicket of woolly nightshade trees we named Chrysler Forge (well, my brother did: I dont really know where that name came from, as it was many years since wed owned a Valiant). We loved exploration, and we loved maps, which were the record of our explorations. The naming and the mapping were an act of possession, of laying claim to a larger world.

My father was a devoted boatie, and we were fortunate enough to spend many happy days cruising Aucklands Hauraki Gulf. Dad never ceased to amaze us with his ability to know exactly where we were, day or night and whatever the weather, simply by looking out for landmarks, lights and buoys and referring to the nautical charts with their spindly black lines and hieroglyphs and pale green shading. We were even more impressedand gratefulthe day we brought a boat to Auckland from Whngrei, beyond our usual cruising grounds. She was slower through the water than we had expected, and night fell before we had rounded Cape Rodney and made familiar waters. By reading the patterns of winking lights and keeping an eye on the compass, Dad brought us surely and safely to anchor in what daylight revealed to be one of our favourite places, Mansion House Bay on Kawau Island. It seemed little short of miraculous, this business of navigation. I had always been interested in maps: now I became obsessed with charts.

I also have a nephew who has always been fascinated by maps and charts. Before he was five, he was capable of following the route we were driving on a road map, which he would keep open on his lap. This habit didnt change as he grew older, and one day, I suddenly realised that the charm of maps was different for him than it was for me. He was an anxious child, and following the route of an outward journey was less about the sense of venturing into a wider world than it was about marking the return. For him, there was only one place of significance marked on the map, and only one cardinal direction: respectively, home and the way home.

When, in my turn, I became a parent, my days all began with me pushing my children up the hill on an arrangement of vehiclesmy son on a trike in front, my daughter on her trike with the front wheel hooked in the tray behind him, me pushing using a handle attached to my daughters trike. We called this bike train. Each day, bike train would make its way from our gate up the road to their daycare, about one and a half kilometres distanta mile in the old money. We had various stops along the way: the bank where wildflowers grew, where my daughter would pick a couple and use them to decorate her handlebars; the traffic lights, where we would impatiently wait for the safe to cross buzzer; a couple of addresses where there were occasionally friendly cats; a phone box where the children would pretend to phone their grandmother to tell her about their forthcoming day; their destination. And in the afternoon, we would make the same journey in reverse. After my son had graduated to primary school, I still kept the same routine with my daughter. One day, she and I drew a map of our habitual route, with all those points of significance marked. That map was more about memorialisation than orientation: we never took it with us, or even consulted it, but I meant to keep it. Years have passed, and I have misplaced the map, or it is lost forever, but it is still printed on my heart.

Maps are records of the known and, as such, they need not be made of lines on paper. Indeed, we are not the only creatures that make them: bees and birds have their own methods of geolocation, and this surely relies upon some kind of mental map. The homing faculty of pigeons is well known, but it pales by comparison with the epic wayfinding facility of migratory birds such as the sooty shearwater, which makes an annual pilgrimage from the subantarctic islands where it breeds to Siberia and then back again to tiny dots of land in the vast Southern Ocean. Bees are thought to use the sun and various landmarks to guide them to the flowering plants where they forage, and then back to the hive. The ability of cats to find their way to former territories when they run away from their owners new homes is legendary. Anyone who has ever owned a Labrador will know the precision with which it will mentally map the location of, say, a discarded half-sausage, and find its way back unerringly many days later. The dogs that the polar explorers took to Antarctica seemed to have had a keen sense of north and south. In 1916, one sledging party, while on the return journey from 80 South, found the need to backtrack, but the dogs refused. It was necessary to drive them northward and then work them in a wide turn to point their noses south again.

Maps, then, are the means by which geographic knowledge is communicated. If you Google worlds oldest map, the result takes you to a description of a stone tablet found in a cave in Spain that, at 14,000 years old, is supposed to be the earliest known depiction of a landscape. But maps are older than that. Human beingsperhaps even their not-quite-human ancestorswere communicating their knowledge of the world to one another long before they came to draw it. The earliest cartographic technology is story. Ancient stories contained useful information, such as the relation of changes in the night sky to the rhythms of nature; they also contained navigational and cartographic information. For posterityor for cultural outsidersthis information can be obscure. But for those intended to hear them, they served as mnemonics. Homers Odyssey , for example, is a baffling story in many ways, loosely based on history and geography. But it has been suggested that it is an ill fit to the places and people it names because the story has been constructed around a set of sailing instructions to anyone circumnavigating the isle of Sicily. The doings of gods, men and monsters are simply a vivid means of making notices to mariners memorable.