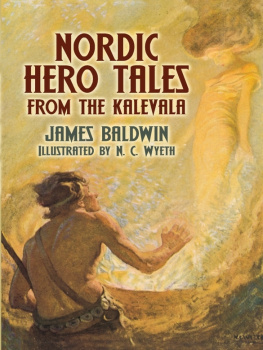

Elias Lnnrot

KALEVALA

The Epic of the Finnish People

Translated by EINO FRIBERG

Introduction by JUKKA KORPELA

Contents

About the Authors

ELIAS LNNROT (18021884) was a Finnish physician, philologist and collector of traditional Finnish oral poetry. Lnnrot created the Kalevala, Finlands national epic, by recording and compiling fragments of folk tales, ballads and other oral poems. Following the publication of the Kalevala, Lnnrot served as Professor of Finnish Language and Literature at the University of Helsinki. He tirelessly promoted the Finnish language and is credited with paving the way for modern Finnish literature.

EINO FRIBERG (19011995) was a Finnish-born American author, noted for his 1989 translation of the Kalevala.

JUKKA KORPELA is Professor of History at the University of Eastern Finland. He has published ten monographs and more than 150 scientific articles on East European culture and history, including The World of Ladoga (Lit. Verlag, Berlin, 2008).

Introduction: The World of the Kalevala and the World of the Forest Finns

The Composition and Context of the Kalevala in Finnic and World Culture

The Kalevala was composed by the nineteenth-century physician and philologist Elias Lnnrot (18021884), who collected folkloric oral poetry among Finnish and Karelian country people in the 1830s and 1840s and from their words created the Finnish national epic presented here. He was drawing on a long tradition. The sixteenth-century Bishop of Turku and Lutheran reformer of Finland, Michael Agricola, knew well the rich folkloric tradition of the pagan country-folk; scholars of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries then collected this material systematically. The Travels (1802) of the Italian explorer Giuseppe Acerbi, who journeyed through Sweden, Finland and Lapland and described the poems and songs of the rural people, became popular among the literati of Europe, and even Goethe was inspired by it, in his Finnisches Lied. Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, the relation of this folklore to Finnish nationality has been a matter of intense academic debate. The Kalevala is Lnnrots contribution to this discussion.

In the national Romantic atmosphere of the time, scholars paralleled the Kalevala epic with classical Greek mythology, and its publication (the old Kalevala in 1835, the new (revised and expanded) in 1849) attracted attention across Europe. Scholars saw the epic as revealing the ancient Finnish pre-Christian mental landscape and world. Later on, the personal artistic input of Lnnrot was emphasized over the original historical mythology. This change was due to a sharp paradigm shift in folkloric studies in the late nineteenth century, which downplayed the value of earlier methodologies.

The rise of historical positivism reoriented the focus of scholarship from mythology and tradition to hard facts, that is, historical archival material and archaeological excavations. This severed the link between history and hagiographic texts, literature and folklore tradition, and affected the study of chronicles; ultimately, it separated literary history from archaeology. Folklore studies also left history behind and instead continued within the discipline of literature. The French historians of the Annales school started to revive the study of the past before the Second World War, but these historians understood that one must widen the scope of history to embrace other branches of scholarship, and this shifted the focus from archival documents alone to all kinds of sources relevant to historical research.

Thus folklore returned to the stage, and the historicity of the Kalevala was revived. From todays perspective the composition of the Kalevala is a monument to the history of science: it and other folkloric poems are a source of ancient Finnic did not mean mechanical rote learning and repetition; instead, each shaman actively and personally interpreted the tradition. Physical poems varied and developed in time and culture, and Lnnrots composition is a genuine part of this tradition. Although it is his personal interpretation, it is not his artistic fiction. Besides storytelling, the poems contain facts about life in this forest-dwelling pre-Christian society. One can find echoes of the ancient past in descriptions of everyday working methods or travelling equipment, the social structure or view of life, but of course the poems are not precise descriptions of historical events and people.

The folklore of the Kalevala was mainly collected in eastern Finland, Karelia and Ingria, although earlier scholars had collected the tradition in the west. Lnnrot proposed in his introduction (1849, ) that the poems were created in Permia on the shores of the White Sea. He referred to the area known as Byarmia in the Viking sagas, but recent studies have shown that this is a most problematic concept.

In the first half of the nineteenth century the ethnologist Matthias Alexander Castrn was quick to make the connection between the mythologies of the Finns and the North Siberian Finno-Ugric speakers. His theory gained international support, as it suited contemporary political relations between the Russian Empire and Grand Duchy of Finland. It could be used to create a vision of an ancient North Eurasian culture, and modern scholars of religion have spoken in similar terms with reference to the circumpolar religion. Another perspective is to link the Kalevala to the old theory that Finno-Ugrian people migrated from the Middle Volga region in ancient times. Lately, genetic studies have confirmed the strong connection between male Finnish and North Siberian Finno-Ugric speakers. However, although the national Romantic visions about the common heroic past are popular with philologists, modern science does not regard long marches and long-lasting mass migrations as realistic in primitive conditions. They belong to the mythic level of the self-identification of populations. The genes depend more on gradual population growth over millennia.

The Kalevala was published in an age when Finnish culture and national identity were taking shape. At the same time, the political context was changing dramatically. Northern Finno-Ugric speakers live in an area extending from the Gulf of Bothnia and south-western Finland to the Arctic Ocean and North Russia. The area of modern Finland had been a part of Sweden from the Middle Ages to 1809, after which it became a Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire until 1917, while Karelia, Ingria and Dvina belonged to the Novgorodian and Muscovite sphere of influence.

The national movement emphasized the Western roots of Finnish culture and described Finnish history as a struggle in which Finland acted as a bridgehead of Western culture against the Eastern threat. In this context, scholars composed a political vision of the glorious common past and togetherness of the Finns and ancient Finland. The Kalevala took up a central ideological position in this mission, so it was essential for historians to define which groups of Finno-Ugrian speakers were the people of Kalevala, or proper Finns, and which were not.

In this atmosphere, the eastern origin of the poems was less popular, so ideas about a Siberian connection withered, too. The main collection areas lay outside the borders of the Grand Duchy, which was a problem for the national-historical interpretation: the mental expansion of historical Finland to Russia was unthinkable. Seeking other explanations for its origins, scholars claimed that the folklore was originally from western Finland and only

Next page