THE KALEVALA

OR Poems of the Kaleva District

COMPILED BY ELIAS LNNROT

A Prose Translation with Foreword and Appendices by

FRANCIS PEABODY MAGOUN, JR.

HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS

AND LONDON, ENGLAND

Copyright 1963 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 63-19142

ISBN 0-674-50010-5 (paper)

Printed in the United States of America

Book design by David Ford

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FOLLOWING PAGE 342

FOLLOWING PAGE 374

The device on the title page, the square (or concentric squares) with externally looped comers, is known in Finnish as hannunvaakuna, in Swedish as Sankt Hans vapen (St. Hanss arms). A favorite decorative motif in Finland today, used also in eastern Karelia and Estonia, it was formerly a common magic and protective sign carved on buildings and objects to safeguard them. In Sweden, too, cattle were protected by it against wizards and ill-disposed persons, and in Norway of old on Christmas Eve it was drawn with pine tar on the doors of houses. The design is found in medieval romanesque carvings, and earlier it occurs on Coptic textiles in Egypt and as far back as the eighth century B.C. on Greek vases.

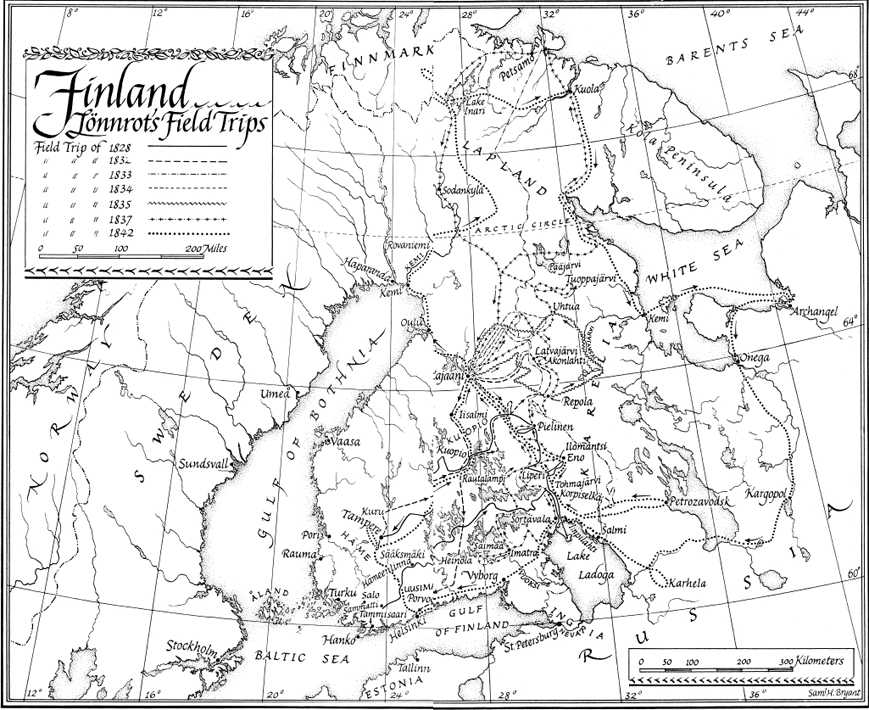

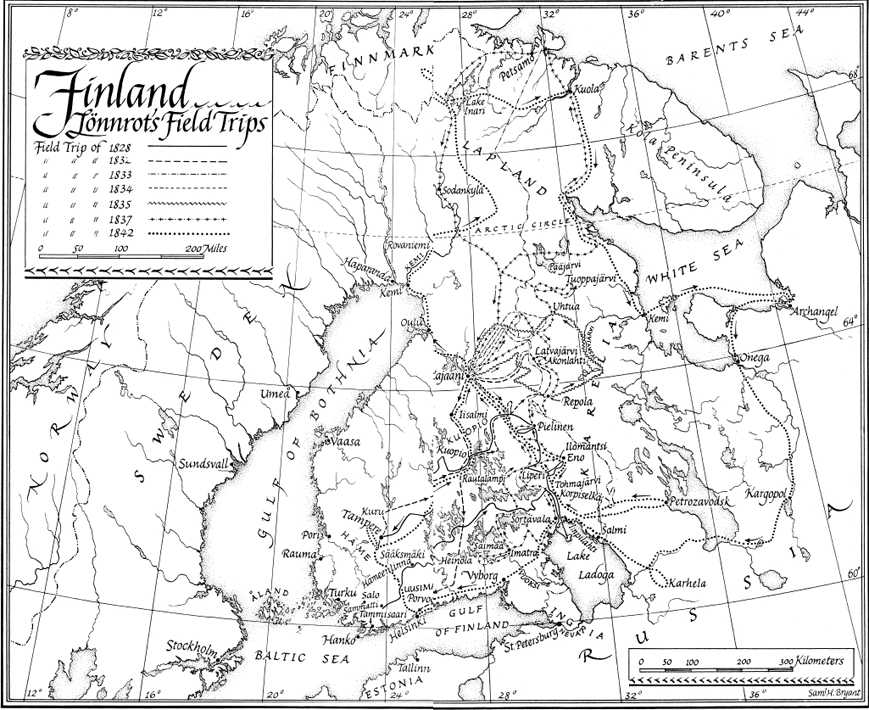

Again and again the Kalevala has been described as the national heroic epic of the Finnish people, a description which, at least outside Finland, has tended to do the work a certain disservice by raising expectations that the reader is not likely to find fulfilled, regardless of what else he may find that is richly rewarding at a poetical, folkloristic, or ethnographic level. Any talk about a national heroic epic is bound to evoke thoughts of the Greek Iliad and Odyssey, the Old French Chanson de Roland, or the Middle High German Nibelungenlied, all of which possess a more or less unified and continuously moving plot with actors who are wealthy aristocratic warriors performing deeds of valor and displaying great personal resourcefulness and initiative, often, too, on a rather large stage. The Kalevala is really nothing like these. It is essentially a conflation and concatenation of a considerable number and variety of traditional songs, narrative, lyric, and magic, sung by unlettered singers, male and female, living to a great extent in northern Karelia in the general vicinity of Archangel. These songs were collected in the field and ultimately edited into a book by Elias Lnnrot, M.D. (18021884), in two stages. The first version appeared in 1835 and is now known as the Old Kalevala; it contained about half the material in the 1849 edition here translated. For the many poems added to this 1849 Kalevala, now the canonical version, Dr. Lnnrot was indebted to a younger song-collector, David E. D. Europaeus (18201884).

Lnnrots title Kalevala is a name rare in the singing tradition; it describes a completely legendary region of no great extent, and is rendered here the Kaleva District. The personal name Kaleva upon which the local name is based refers to a shadowy background figure of ancient Finnish poetic legend, mentioned in connection with assumed descendants and with a few nature or field names. The action, like that of the Icelandic family sagas, is played on a relatively small stage, centering on the Kaleva District and North Farm (these are discussed in the Glossary). The actors are in effect Finno-Karelian peasants of some indefinite time in the past who rely largely on the practice of magic to carry out their roles. Appearing at a time when there was little or no truly bellelettristic Finnish literature, the Kalevala unquestionablyand most understandablybecame a source of great satisfaction and pride to the national consciousness then fast developing among the Finns, who had been growing restive under their Russia masters. To some extent the Kalevala thus became a rallying point for these feelings, and permitted and in a measure justified such exultant statements as Finland can [now] say for itself: I, too, have a history! (Suomi voi sanoa itselleen: minullakin on historia!).

Lnnrots own comments in his prefaces (see ) make clear that one of his chief aims was to create for Finnish posterity a sort of poetical museum of ancient Finno-Karelian peasant life, with its farmers, huntsmen and fishermen, seafarers and sea-robbers, the latter possibly faint echoes from the Viking Age, also housewives, with social and material patterns looking back no doubt centuriesall reflecting a way of life that was, like the songs themselves, already in Lnnrots day destined for great changes if not outright extinction. Thus, from Lnnrots point of view the many sequences of magic charms and wedding lays, at times highly disruptive to the main narrative, are for what they tell of peasant beliefs and domestic life quite as significant as the narrative songs about the Big ThreeVinminen, Ilmarinen, and Lemminkinen.

Owing to the special character of its compilation or concatenation, the Kalevala possesses no particular unity of style apart from the general diction of the Karelian singers and the indispensable ubiquitous traditional formulas discussed below. Comprising miscellaneous materials collected over many years from many singers from all over Karelia and some bordering regions, these poems range in style and tone from the lyrically tragical, as in ), with their keen, detailed observations on the daily life of the Karelian peasant. All call for quite varied styles in any English rendering.

The digests at the beginnings of the poems are Lnnrots and were written in prose. Lnnrot is also the artless composer of , lines 513620; both these passages are pure flights of Lnnrots fancy, and, despite a semblance of autobiography, bear no relation to the authors life.

On reading the Kalevala. In reading a new poem or a sequence of poems it is normal to begin at the beginning and read straight ahead, but in the case of the Kalevala this natural procedure has little to recommend it, since in a general way the present order of the poems is quite arbitrary, differing considerably, for example, from that of Lnnrots 1835 Old Kalevala. Instead of starting with and following); though not in sequence, these can easily be picked out from the table of contents. One might then pass on to the Ilmarinen stories and to those dealing with Kullervo. The Vinminen poems form a somewhat miscellaneous group, and Vinminen keeps appearing here and there in a large number of poems dealing primarily with the other principals.

The many magic charms, inserted here and there, can usually be skipped on a first reading of the poem or poems in which they occur, though some of the shorter are entirely appropriate in their contexts and do not appreciably obstruct the flow of the narrative. Some of the more extensive charms and series of charmsfor example, the Milk and Cattle Charms of can be enjoyed when read out of context. In the table of contents the presence of charms in the poems is always indicated. For the translation of many additional Finnish magic charms (loitsurunot) the reader is referred to John Abercrombie, The Pre-and Proto-historic Finns..., II (London, 1898), 65389.

There are surely many possible approaches to a first reading of the Kalevala,

Next page