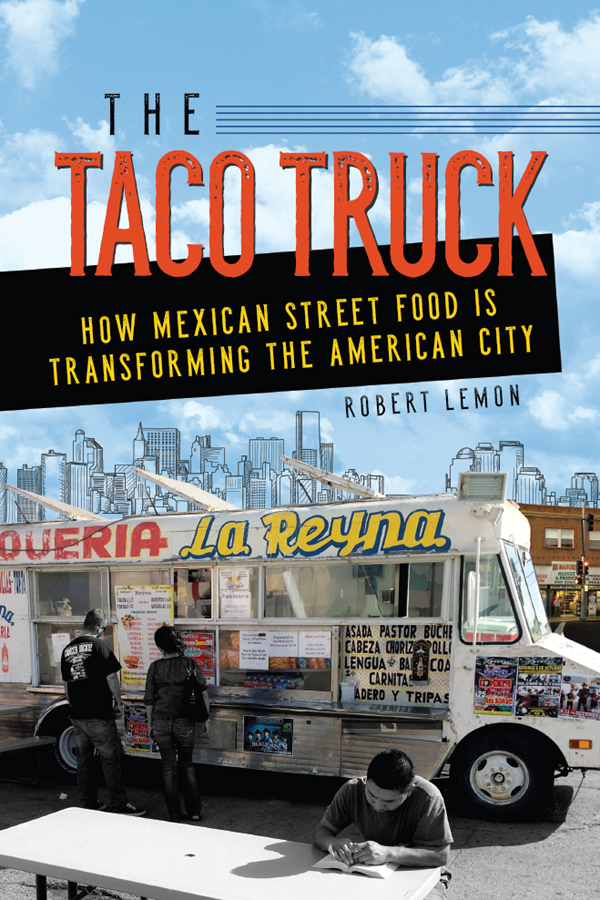

THE

TACO TRUCK

HOW MEXICAN STREET FOOD IS TRANSFORMING THE AMERICAN CITY

ROBERT LEMON

FOREWORD BY JEFFREY M. PILCHER

2019 by the Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Maps of the areas discussed in this book can be found at

https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books.lemon/taco_truck

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lemon, Robert, 1979 author.

Title: The taco truck : how Mexican street food is transforming the American city / Robert Lemon.

Description: Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018056752| ISBN 9780252042454 (hardback) | ISBN 9780252084232 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Hispanic AmericansSocial life and customs. | Mexican AmericansNutrition. | Food trucksUnited States. | TacosUnited States.. | Food habitsSocial aspectsUnited States. | United StatesSocial life and customs21st century. | BISAC: SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / Hispanic American Studies. | COOKING / Regional & Ethnic / Mexican. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Emigration & Immigration.

Classification: LCC TX361.H57 L47 2019 | DDC 641.84dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018056752

E-book ISBN 9780252051296

Cover images: Taco truck in Tulsa Oklahoma (photo by Robert Lemon); skyline background image (iStock.com/Terriana).

To my grandmother, Rosalina B. Gonzalez (19112006),

for all the love she gave me through her cooking.

FOREWORD

JEFFREY M. PILCHER

The local mobility of taco trucks represents a microcosm of geographical and social mobility in the twenty-first century. Food vendors spread across the United States as part of the great Mexican migration that began with the peso crises of the 1970s and 1980s, accelerated with the North American Free Trade Agreement in the 1990s, and largely ended with the United States own financial crisis in 2008. Like previous generations of migrants who found opportunities in small food businessesthink of hamburgers, pizza, chop suey, and deliMexicans gained a measure of social mobility by traveling to find work, or at least to find a customer willing to pay for a cheap and tasty meal of carne asada. But for a generation of Americans facing downward mobility due to corporate offshoring and anti-union politics, and who are increasingly unwilling to risk moving in search of better employment, Mexican workers who would take the most unenviable jobs became a target of nativist outrage, as during the 2016 election when populists fulminated against a taco truck on every corner. Nevertheless, attempts to treat taco trucks as an immigration problem fundamentally misrepresent the situation for countless U.S. citizens who make a living by vending and for whom restrictive city ordinances and ongoing police harassment are civil rights issues.

In seeking to resolve these political and social conflicts around food and mobility, we would do well to remember their historical antecedents. In the 1880s, American migrants to the cities of San Antonio, Texas, and Los Angeles, California, found the local Mexican population and food to be simultaneously threatening and alluring. Tourists eagerly sought out street vendors known as chili queens to sample their tamales and chili con carne, even while fearing the unaccustomedly piquant taste and the risk of gastrointestinal disease. Health reformers soon arrived on the scene, seeking not to improve Mexican neighborhoods access to clean water and sewage, which was the real cause for concern, but rather to restrict the vendors to zones of tolerance that were shared with prostitutes. By essentially criminalizing chili con carne, police were free to harass Mexican food (and sex) workers, while still leaving them accessible to adventuresome tourists, an arrangement that persisted until the civil rights movement.

Today, that movement's gains have never seemed more imperiled, as taco trucks have replaced nineteenth-century tamale carts as racialized symbols of criminality. Robert Lemon's book therefore provides a timely account of the myriad small and large ways that privatization and gentrification have restricted the rights of citizens and residents to the use of our cities. Using techniques of urban geography, he maps the evolving spatial dynamics of twenty-first-century Jim Crow, which attempts to segregate racialized sites of production from elite white spaces of consumption within the neoliberal city. In interviews with taco truck vendors, Lemon describes the strategies they use to navigate this hostile urban terrain and reach their customers. The book also provides an invaluable account of community organizers and progressive municipal officials who have pioneered ways of supporting vendors with the logistical and legal infrastructure needed to prepare healthy food, thereby positively contributing to urban landscapes. But perhaps the most important point is that taco truck workers, simply through their everyday presence, occupying city streets and selling food to hungry customers, embody the democratic ideals of liberty and equality for some of the most downtrodden within American society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to begin by thanking Steven Hoelscher for helping me develop a sound geographical framework for this project. His insights and critical assessments of my work were always constructive and motivating.

Indeed, very many mentors and scholars along the way provided great input to how I could bring distinct themes of urban geography, cultural geography, architecture, landscape architecture, city planning, food studies, Latino studies, and Mexican immigration together. Bill Doolittle has always provided pragmatic evaluations of theoretical issues. Elizabeth Engelhardt helped me tie the work into food studies; Rebecca Torres offered astute insights into Mexican immigration to the United States and how best to incorporate other socioeconomic Latino issues into cultural landscape studies. I owe many thanks to Paul Adams as well: his brilliant comments and suggested readings throughout my entire research process helped me to better establish many of my theoretical points, and he kept me from following blindly into a number of prevailing dogmatic positions. Furthermore, I would like to thank John Radke, who encouraged me to pursue the cultural geography of taco trucks. And I owe a debt of gratitude to Jefferey Pilcher for his historical perspective of Mexican food as well as his time in writing the foreword to this book.

This research would not have come to fruition without all the people I interviewed over the past few years, especially the taco truck owners who so generously shared their personal stories and their cuisines with me. Without their big-heartedness and willingness to work with me on this study, I would not have had a book to write. Moreover, my interaction and experience with these individuals gave me keen insight to the hopes and aspirations of so many migrants who struggle every single day to carve out a space for themselves in the United States. I cannot mention many individuals by name because they are undocumented. But they know who they are; and I have made it clear to them, throughout my research, that this work is as much a chronicle of their stories and struggles as it is a scholarly explanation of their everyday spaces. However, I can name two individuals: George Azar and his mother, Mercedes Azar. George Azar owns a taco truck in Sacramento, California. When I first met George, he was kind enough to spend countless hours with me going through personal taco truck archives and recounting the history of taco trucks in Sacramento. His recordkeeping of the taco truck conflicts in Sacramento provided me incredible documentation to strengthen my argument in . His and his parents generosity to me not only made my research attainable but also pleasurable.