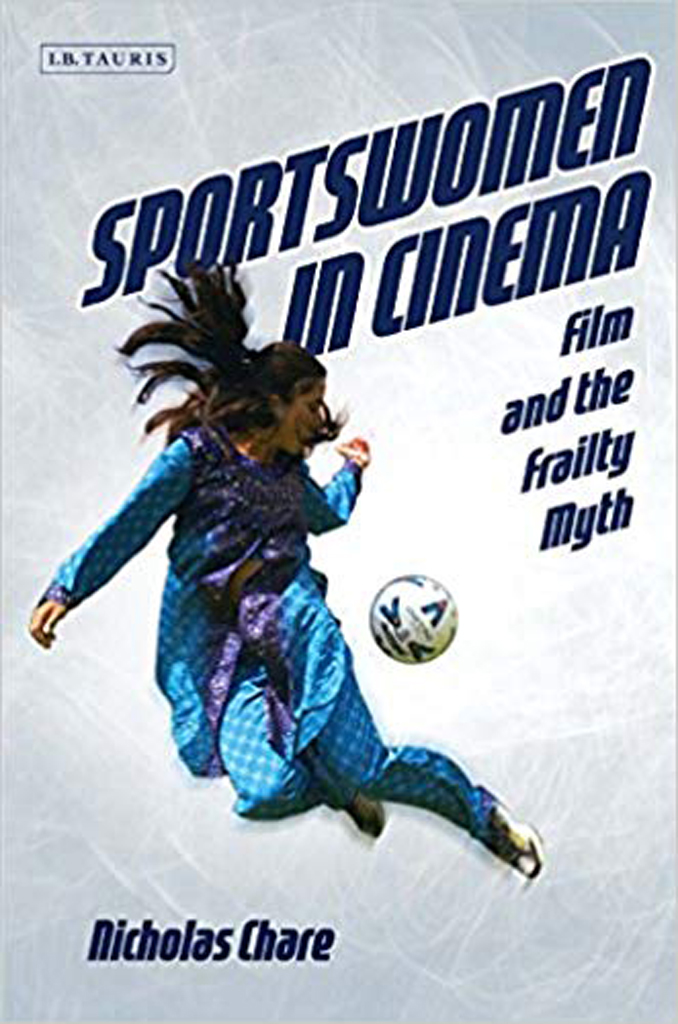

Nicholas Chare is Associate Professor of Art History in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at the Universit de Montral. His books include Auschwitz and Afterimages and After Francis Bacon. He is currently co-authoring, with Dominic Williams, a book about the Scrolls of Auschwitz entitled Matters of Testimony.

To Adrian, Fred and Griselda

To Adrian, Fred and GriseldaContents

Many intellectually generous, open-minded colleagues, past and present, have contributed valuable ideas during the ten years it has taken to bring this project to completion. I am particularly grateful to the Faculty of Arts at the University of Melbourne for awarding me a grant that allowed me to engage in the research that was needed to write the chapters on boxing and surfing, enabling me to finish the book. I would also like to acknowledge the administrative and curatorial staff of the Australian National Maritime Museum, the Powerhouse Museum and the World Rugby Museum, for their help and assistance.

I am especially thankful to my colleagues in the Gender Studies programme at the University of Melbourne, Jeanette Hoorn, Maree Pardy and Kalissa Alexeyeff, for their friendship and encouragement and also to Barbara Creed, Wendy Haslem, Angela Ndalianis and Mark Nicholls in Screen and Cultural Studies for their support. In addition, I am also grateful to my students on the courses Behind Visual Pleasure, Introducing Gender: Sex, Sport and Film and Subjectivity and Sexuality in Art since 1960 for sharing their insights. For Subjectivity and Sexuality in Art since 1960, which I taught at the University of York, sports journalist Marina Hyde gave generously of her time and insights. She merits special thanks for inspiring both me and my students with her genuine passion for sporting equality. I am also grateful to my tutors on Introducing Gender, Lauren Bliss, Katharina Bonzel, Felicity Ford, Jemma Hefter and Caroline Wallace, for perceptive comments in relation to several of the films that feature in the book.

Specific debts of intellectual gratitude go to Chenez Dyer-Bray for encouraging my thinking in relation to sound and feminine comportment, Muyun Liu for imparting her knowledge of Chinese cinema, and Rachel Macreadie for sharing her insights into self-defence scripts as cathartic narratives. For direct or indirect assistance with particular sports related questions, I am obliged to the bodybuilder Niall Richardson, the boxer Mischa Merz, the climbers Richard Heap and Justin Ions, the runner Betsy North, the surfers Adam Bartlett and Michael Price, and the tennis player Alexander Fitzgerald. I am also thankful for the intellectual friendship of Rina Arya, James Boaden, Justin Clemens, Paul Davies, Michelle Gewurtz, Mark Hallett, Anne Karpf, Peter Kilroy, David Lomas, Silvestra Mariniello, Laura U. Marks, David McInnis, Jeremy Melius, Eddie Paterson, Nathanael Price, Adrian Rifkin, Patricia Rubin, Lesley Stirling, Dan Stone, Marcel Swiboda, Sharon Lin Tay, Francesco Ventrella, Liz Watkins, Anthony White, Emma Wilson and Dominic Williams.

Special thanks must go to my commissioning editors at I.B.Tauris, Philippa Brewster, Anna Coatman and, particularly, my production editor, Lisa Goodrum. They have been a pleasure to work with from start to finish. The book would also not have been possible without the love and kindness of Julie, Peter and Sara Chare and Angela Mortimer and Esther Chare. My deepest debt, however, is to Griselda Pollock, a continuing source of intellectual inspiration and a model of academic generosity.

Limbering Up

Stick It (Dir. Jessica Bendinger, USA, 2006), a film about a teenage delinquent with a love of gymnastics who finds redemption through the sport, begins with a sequence of three freestyle BMX riders performing air tricks in the grounds of a house that is under construction. The cyclists are interrupted by some skateboarders who challenge them to a competition. One of the boarders performs an elaborate set of tricks before slamming into a wall. A hooded rider then executes an even more daring routine before smashing through the windows of the house, jamming their front wheel between some balusters, and setting off an alarm. The two groups then scatter to evade police. The daredevil rider, who removes their hooded sweat top whilst running away in a bid to look less of a suspect, is revealed to be a woman, the star of the film, Haley Graham.

The opening to Stick It plays with audience assumptions based on stereotypes of gendered behaviour. BMX is typically viewed as a male pursuit. The film therefore indicates early on that it will challenge preconceptions. It forms one of a steadily increasing number of films that centre on female athletes. Until recently, the genre of the sports film was predominantly a male preserve. Aaron Baker, recognising this, suggests that the competitive opportunities offered to male athletes in most sports films justify patriarchal authority by naturalising the idea of men as more assertive and determining, while women generally appear in the secondary role of fan and dependent supporter. These films form the subject of this book.

There have, as Jayne Caudwell has recognised, been few scholarly critiques of sports films that focus on women Baker, Crosson and Tudor all devote a chapter of their respective books to gender issues. Sportswomen in Cinema is, however, the first study to focus exclusively on films about female athletes.

The book considers both documentary and fiction films and, although not comprehensive, strives to provide a sense of the history and geographical diversity of films featuring sportswomen. Each chapter is centred upon a particular form of sport, including bodybuilding, boxing, climbing, surfing, tennis and track and field. Cheerleading, which might seem an obvious choice for inclusion given the success of Bring it On (Dirs. Peyton Reed & Jim Rowley, USA, 2000), is not addressed. The cheerleader is, as Tudor recognises, usually in a marginal, supportive position to sportsmen. The sportswomen in the film, for example, are sexually objectified at times, shown dressed in bikinis. The films of interest here, however, predominantly introduce some kind of challenge to phallocentrism as it is embodied in sport and sports cinema.

Team sports, including basketball, football, handball and hockey, are largely dealt with together in demonstrates, this is no longer the case with a number of important films released in the last 15 years including, most notably, the football related Bend it Like Beckham (Dir. Gurinder Chadha, UK, 2002). The chapter focuses, in particular, on the growing number of films about sportswomen, including Chak De! India (Dir. Shimit Amin, India, 2007) and Forever the Moment (Dir. Im Soon-rye, South Korea, 2008), that are produced outside of an American and European cinematic context.

This book differs significantly from earlier works in its approach. Baker and Crosson, for example, draw on Marxist thinking, particularly Antonio Gramscis idea of hegemony, to address how sports films usually function to maintain dominant ideas about masculinity. examines how films about women bodybuilders that explore the phenomenon of muscle worship provide a means by which to think beyond the penis-vagina coital model of sex.

Sports films now often exploit these fetishes as part of their continuing sexual objectification of female athletes.

To Adrian, Fred and Griselda

To Adrian, Fred and Griselda