Letters from Turkey

Letters from Turkey, considered the best Hungarian prose of the eighteenth century, is written by Kelemen Mikes, a Transylvanian nobleman who went into exile with Ferenc Rakoczi II, the Prince of Transylvania, after the War of Independence in 1704 - 1711 in which the Prince fought to preserve independent Transylvania. The Prince and his entourage spent some years in France, and were then invited to Turkey by Sultan Ahmed m, going there in 1717. Some of the party eventually left, but, like Rakoczi, Mikes spent the rest of life in exile in Turkey.

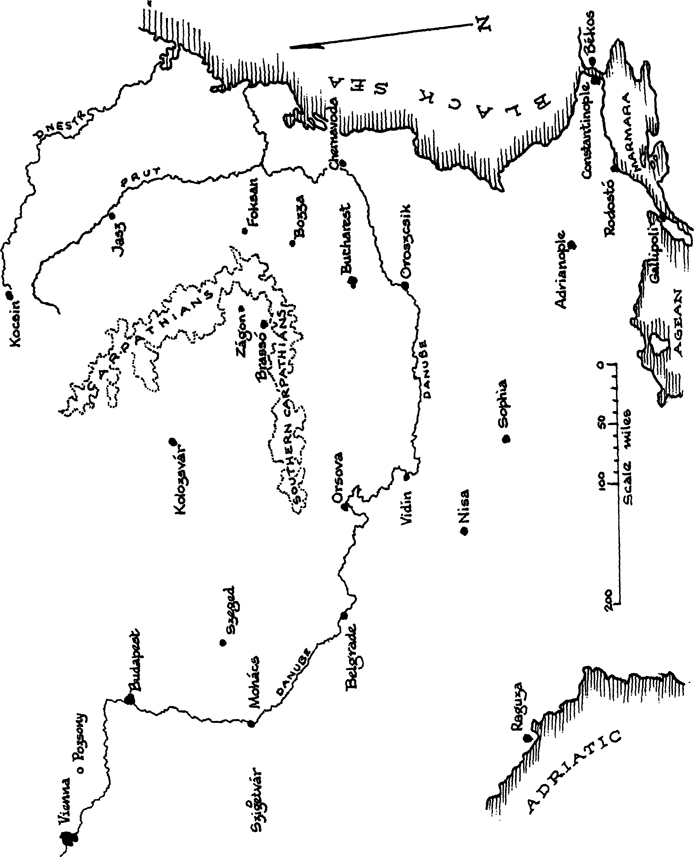

This memoir had a considerable vogue in Transylvania at the time, and Mikes writes in a well-established tradition. The 207 letters, never before translated from Hungarian, were addressed over some forty years to an aunt in Constantinople. In them, Mikes speaks of the Hungarians daily life, their hopes and disappointments, and of current events in Turkey and beyond; he describes the deaths of some of the party including that of the Prince himself. He also gives an account of a military campaign along the Danube and an embassy to Moldova, ranging over religious, historical and philosophical topics and recounting numerous anecdotes. All the while his patriotic feelings never leave him, nor does his affection, not unblinkered, for his Prince. The last letter, written four years before his death, sees him become head of the Hungarian community in Turkey, last survivor of the original band of Transylvanian nobles exiled to a far country.

Bernard Adams, the translator and editor of this volume studied at Pembroke College, Cambridge. He was a Fellow of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London and specialises in the translation of Hungarian literature.

First published 2000 by

Kegan Paul International Limited

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Bernard Adams, 2000

Transferred to Digital Printing 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-7103-0610-4 (hbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

More was lost at Mohcs goes the proverbial Hungarian response to news of catastrophe, for it was at Mohcs, to the west of the Danube near the frontier with modern Croatia, that on 29th August 1526 an Ottoman army under Suleyman the Magnificent annihilated a Hungarian force led by Lajos II, who lost his life in the ensuing flight. The consequence for the Hungarians of this defeat was loss of independent statehood, with the division of the country into Turkish Hungary (occupied territory), Royal Hungary (ruled by the Austrian Hapsburg dynasty) and Transylvania.

For Turkish Hungary the period of occupation was a wretched time, during which much damage was done by the conquerors boundless exploitation of the country, large areas of which became virtually uninhabitable. The situation in Royal Hungary was little better. Not only was the new ruler foreign, claiming the crown through rel ationship to the deceased Lajos, but also the frontier was ill-defined and worse defended, with cross-border raids by the Turks a constant feature of life.

In Transylvania, however, the extreme east of the country, things were rather better. The mountainous terrain was less vulnerable to military action than the plains to the west, and the Sultan remained content to have the Princes as vassals whose tribute ensured their semi-autonomous status. After Mohcs Transylvania, always a distinctive element of Greater Hungary by virtue of its separate constitution under a viceroy, became in effect an independent state. Refugees from Turkish Hungary went there rather than to Royal Hungary, and Transylvania attained international importance both as the defender of Hungarian liberties against the Hapsburgs, and as the bulwark of Protestantism in Eastern Europe.

The Rkczi family was of princely Transylvanian stock, and when, following the death of Suleyman at Szigetvar in 1566, Ottoman power began slowly to wane, they and their kinsmen were at the forefront of opposition. Count Mikls Zrinyi, commander of Szigetvar, who led his remaining men in a sally to death when the month-long siege by prodigious odds had become hopeless, was an ancestor of Ilona, wife of Prince Ferenc Rkczi I and mother of Ferenc II; Zrinyisgreat-grandson, Viceroy of Croatia, strove by activity military, political and literary to liberate Hungary from the Turks. It was Ids hope that Gyrgy Rkczi II, Prince of Transylvania 164860, would emerge as leader of a united Hungary, but this was not to be, and Zrinyi spent his final years in unsuccessful endeavours to bring the Austrians into a war against the Turks. He died in 1664, killed in a hunting accident, and it was not until 1686 that Buda was taken by the international forces under the Duke of Lorraine. By the end of the century the Turks were almost completely expelled, and the Peace of Karlowitz (1699) formally ended their occupation of Hungary.

Prince Ferenc II, by far the best known internationally of his family, was bom in 1676, the year of his fathers death; his mother subsequently married the kuruc leader Imre Thkly, who reigned briefly as Prince of Transylvania in 1690. Removed from parental care by the Austrian authorities in 1688, young Ferenc was educated in a Jesuit school in Bohemia and at the University of Prague, which instilled in him a profound religious sense and inculcated a much more pacific view of the world than his turbulent ancestors had held; he was even dissuaded from speaking Hungarian. On return in 1694 to the family estates at Srospatak he became aware of the plight of his compatriots and almost by right of inheritance found himself a leading figure in the kuruc resistance to the Austrians, who had by this time replaced the Turks as oppressors of the Hungarians. In 1701, discovered in a plot to enlist foreign support, he was imprisoned by the Austrians and condemned to death but escaped with the aid of his wife, to spend two years in Poland. His leadership in the War of Independence from 1703 onward resulted in his election in 1704 and installation in 1707 as Prince of Transylvania; in 170S he was elected leader of the Hungarian confederated estates, and in 1707 the Hapsburgs were formally discrowned by the Hungarian Parliament. Initially he received support from Louis XIV, but when, as an eventual consequence of the French defeat at Blenheim, this support was withdrawn Rkczi was obliged to end the struggle, and with a number of followers left Hungary in February 1711, shortly before the signing of the Treaty of Szatmr that brought the war to a close.