Published by

The University of Alberta Press

Ring House 2

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 2E1

www.uap.ualberta.ca

Copyright 2019 Naomi K. Lewis

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Title: Tiny lights for travellers / Naomi K. Lewis.

Names: Lewis, Naomi K., 1976 author.

Series: Wayfarer (Edmonton, Alta.)

Description: Series statement: Wayfarer series

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190053437 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190056843 |

ISBN 9781772124484 (softcover) | ISBN 9781772124750 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781772124767 (Kindle) | ISBN 9781772124774 (PDF)

Subjects: LCSH: Lewis, Naomi K., 1976TravelEurope. | LCSH: Grandchildren of Holocaust survivorsCanadaBiography. | LCSH: Jews, CanadianBiography. | LCSH: JewsIdentity. | LCSH: Identity (Psychology) | LCSH: Intergenerational relations. | LCSH: Judaism and secularism. | LCSH: EuropeDescription and travel.

Classification: LCC FC106.J5 L48 2019 | DDC 305.892/40971dc23

First edition, rst printing, 2019.

First electronic edition, 2019.

Digital conversion by Transforma Pvt. Ltd.

Editing by Kimmy Beach.

Proofreading by Maya Fowler Sutherland.

Map by Wendy Johnson.

Book design by Alan Brownoff.

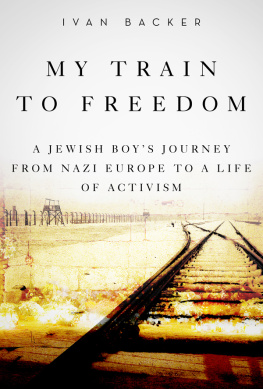

Cover image: Wilfred Kozub, Night Vision , 2011, acrylic on canvas, 38 33.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written consent. Contact University of Alberta Press for further details.

University of Alberta Press supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with the copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing University of Alberta Press to continue to publish books for every reader.

University of Alberta Press gratefully acknowledges the support received for its publishing program from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Government of Alberta through the Alberta Media Fund.

In memory of Josua van Embden

Despite himself, he has assumed the role of the wise son at the Passover seder, who enters so personally into shared Jewish experience that its history becomes his memoir.

REBECCA GOLDSTEIN, Betraying Spinoza

And I wondered, with mounting anxiety, what I was to do here, what I was to think.

ALAIN DE BOTTON, The Art of Travel

THE SKY WAS FULL OF HUMANS , and I was one of them. Way above the Atlantic Ocean, I exhaled, and had no choice but to refill my lungs with air expelled from inside the strangers crammed close around me. According to the digital map on the seat-back in front of me, we were about halfway there. My nose began to tingle, and that could only mean one thing: I would grow a cystic pimple, a massive throbbing lump, right there, a millimetre above my right nostril. At thirty-nine, I was travelling alone for the first time, and my reasons for crossing the ocean seemed, from this vantage, murky at best.

An attendant came by with his cart, and I asked for a coffee. Leaning my head back, I pressed the hot cardboard cup under my nose against the tingling spot, since heat often warded off cysts before they really got going. Oh, go away, painful nose-swelling, please go away. Soon Id meet relatives I barely knew, and Id face strangers for the rest of the month. Not to mention Matteo. Hotter than optimal, painful, really, and I didnt want to burn myself, had to get it just right. But, I thought, this is a particularly sensitive spot, thats why it hurts so much. Three minutes is usually good. How long has it been? Okay, three minutes starting now. I closed my eyes.

There were approximately half a million humans in the sky at any given moment, travelling at hundreds of miles an hour. Thats a million socks and a million shoes, not counting all the shoes and socks packed in a million suitcases. Arms and legs, and human hair, each strand growing in its follicle. Bodies. Bodies of people who died on holiday and whose remains must be buried at home. Bunnies in cages, cats and dogs. Urine. Germs! E. coli and HIV. And tumours, and bedbugs.

Three minutes. Okay. I put the coffee cup down.

Lingerie and parkas, I thought. Jeans and lipsticks. Paper and ink. All just zooming through the sky, all day every day.

I touched the spot under my nose, and the skin didnt feel so good. When I made my way down the aisle to the toilet, and looked in the mirror, the end and underside of my nose appeared, sure enough, an angry red. Burnt. The rest of my face looked oily and yellowish in that special plane-bathroom glow that seems a perfect embodiment of the urine-and-disinfectant smell that accompanies it. Even my eyes and hair were tinged with sickliness. I folded the door in toward me, stepped out of the bathroom, and scanned the scene before me, a grid of indistinct blue chair backs and lolling heads. This was why I had never travelled alone before: lost already, on the plane. Breathing into my ribs to ease the stab of panic, I wandered the plane for at least ten minutes, peering into each row for my new yellow headphones before I spotted them in the middle of a chair, my white notebook tucked into the mesh pocket with the magazines and puke bag. My row-mates jostled to let me back in, and I sat for several minutes with the notebook gripped in both fists before opening it again. I felt like I did when I was twelve, when Id kept my navy-blue diary tucked between my mattress and the wall, tucked it into my schoolbag each morning, checked for it throughout the day, reaching in to feel the comforting cloth cover against my palm.

Inside the white notebook, Id tucked my retyped and printed-out pages of my grandfathers seventy-three-year-old journal.

In the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and forty-two, when brute barbaric violence and injustice reigned over the greater part of Europe, I was one of the hundredsif not thousandswho by a secret escape fled the violence and injustice which directly threatened their lives. What follows here is a short chronicle of that pilgrimage to safer places.

Jos van Embden had written these words long before he became a husband, or a father, or my Opa. In July 1942, now exactly seventy-three years ago, he was thirty-three years old. A young man, tall and blue-eyed, his blond curls styled into a meticulous side-parted pompadour.

It is merely a matter-of-fact travelogue, from which few, if any, extraordinary or shocking facts will be omitted. Let it be noted by way of an excuse, that it is not my intention to compose something meant for publication. But now that I am here in the unoccupied part of France and have foundat least for nowa somewhat safe anchorage, I want to write these facts down for myself and possibly also for relatives and friends in this moment when all the peculiarities are still clear in my mind, so that later on when we live again under happier and more humane circumstances, the memories of all of this will not have faded completely.

Joss account covered two weeks, during which he escaped from German-occupied Europe. Hed been fired from his job at Royal Dutch Shell, with the heartfelt regret of his employers. The new German government had passed laws barring him from working, from visiting movie theatres, from riding a bicycle, or riding in a car, or riding a tram, unless on the front platform. He was forbidden from leaning out of windows, or using balconies that faced the street, or wearing clothing that had not been embossed with a yellow star reading Jood . On July 15th, exactly seventy-three years before I sat in that plane, all Amsterdam telephone subscribers were required to declare their race, and anyone who admitted to being Jewish had their service cut off. Worse things were coming, there was no doubt. Opas brother was going into hiding; his mother, already elderly, was sure no one could be bothered to track her down.

Next page