Now I will tell you stories of what happened long ago.

There was a world before this.

The things that I am going to tell about happened in that world.

Some of you will remember every word that I say,

some will remember a part of the words,

and some will forget them all

I think this will be the way, but each must do the best he can.

Hereafter you must tell these stories to one another.

You must keep these stories as long as the world lasts;

tell them to your children and grandchildren

generation after generation

When you visit one another, you must tell these things,

and keep them up always.

Henry Jacob, elder of the Seneca people, 1883

The Harvest Song

Painted in Taos Pueblo, New Mexico (Southwest) by Eanger Irving Couse, c.1920

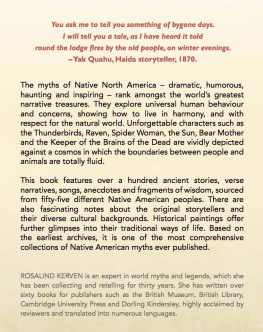

First published in the UK by Talking Stone 2018

Text copyright Rosalind Kerven 2018

Talking Stone

Swindonburn Cottage West, Sharperton

Morpeth, Northumberland, NE65 7AP

The moral right of Rosalind Kerven

to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or

otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher

ISBN: 9781912643752

Cover illustration:

Haida Double Thunderbird, unknown artist, 1880

To the best of the publishers knowledge,

this work and all the text illustrations

are out of copyright and in the public domain

Patterns and motifs in chapter headings are based on

19th century Native American designs from each cultural region

Dedicated to the wild creatures of North America,

without whom these stories would not have been told.

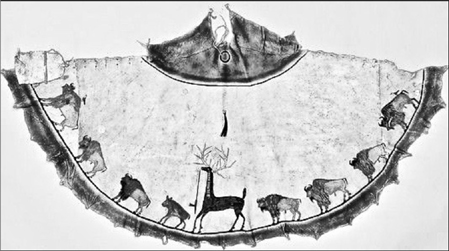

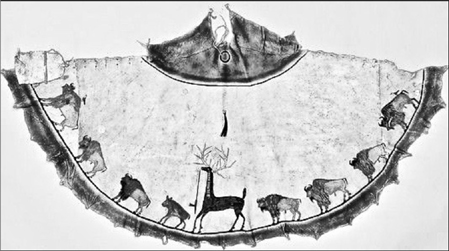

Kiowa tipi cover

Great Plains, 1904

The author owes a great debt to many men and women, long dead: the Native American people who generously shared their ancient stories with outsiders; and the ethnologists and other story collectors who took the trouble to transcribe them and record them for posterity. Where their names are known, these are given in the notes after each story.

CONTENTS

TERMINOLOGY AND NAMES

There is no universally accepted term used to cover the numerous indigenous peoples of North America those who inhabited the continent before the arrival of European settlers from the early 16th century. For most of the ensuing centuries, outsiders called the people Indians a term derived from the fact that the original European explorers of the Americas mistakenly believed they had arrived in India. Some now consider this term unacceptable. It has also become somewhat confusing, since people with roots in India itself also live in North America. Since the 1950s, Native American has increasingly been used as a more accurate and respectful name, but this too is not universally accepted. In the United States Indian is still widely used, with many groups using the term on their own websites, whilst others prefer to avoid the issue. Inhabitants of Alaska are often called Alaska Natives. In Canada, the preferred terms are First Nations, Aboriginal Peoples or Indigenous Peoples.

Against that background, this book uses the term Native American, believing it to be accurate, all-embracing and generally inoffensive.

The use of the word tribe is also controversial; some regard it as derogatory, yet many Native American peoples own websites use it. Where applicable, this book uses the word people instead.

When the stories in this book were collected, outsiders tended to call the various Native American peoples by names which they did not use for themselves. Since this is a historical collection, it uses the names recorded in the original texts; however, in the factual introduction to each cultural section, and under each story title, this is followed by the correct name in parentheses.

Where direct quotes from old sources are used, the original wording has been reproduced.

INTRODUCTION

This book presents some outstanding examples of historical Native American stories, collected in what is now the the United States and Canada between the early 17th and early 20th centuries.

By the latter date, most of North Americas great indigenous civilisations had been either exterminated or severely damaged by white settlers, who imposed their lifestyle right across the continent. However, even 100 years ago, a good many Native American survivors still remembered their ancestral traditions. Fortunately, some were willing to share these with ethnologists. They in turn were eager to record them before they were lost for ever, and published their studies of Native American cultures over a number of years in books and academic journals. Preserved alongside them are less formal works written by explorers, travellers, geologists and missionaries. Within these archives most of which can now be viewed in the original documents online are thousands of sacred myths, oral histories, local legends and folk tales.

CHOOSING THE STORIES

Research for this book took over three years, and involved examination of nearly 2,000 stories from 130 different peoples. The oldest ones were collected by Jesuit missionaries in the 1630s. A cut-off date of 1920 was set, in order to present only material firmly rooted in the past, when the old cultures were more likely to be thriving. For example, a Cheyenne chief sharing his traditions with an ethnologist around 1907 said:

My mother told me all these things. She is over a hundred years old, and she learned these stories from her grandmother.

Although myths are living entities, still being retold and developed today, more modern versions tend to have subtly different details and meanings.

The stories were selected for their world heritage qualities their expression of universal human concerns, their powerful allegory and imagery and their inspirational teachings; also for their strong plots, memorable characters and satisfying conclusions.

RETELLING THE STORIES

Rather than simply reproducing the oldest written texts, the stories have all been sensitively retold. This is because, although the sources appear to accurately record the narratives, some of the original transcriptions were themselves retellings, whilst others fail to convey the flavour and colour of the oral storytellers.

Many of the original texts comprised ethnologists summaries or recounts as dry, factual records. Others, collected by sympathetic non-experts, were retold with somewhat less rigour than their more academic peers. Less common were stories recorded in the Native American narrators actual words, formally and slowly dictated, often in the mother tongue, then translated into English, and transcribed sentence by sentence. The laboriousness of this method is described by J. William Lloyd in his collection of Pima (Akimel Oodham) stories,