Published in 2021 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2021 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2021 The Rosen

Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Xina M. Uhl: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Spy games: cracking government secrets / edited by the

New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: New York Times Educational Publishing, 2021. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823516 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823509 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823523 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: SpiesJuvenile literature. | Espionage Juvenile literature. | CryptographyJuvenile literature. | Intelligence serviceJuvenile literature. | Military intelligence Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC UB270.5 S654 2020 | DDC 327.1209045dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

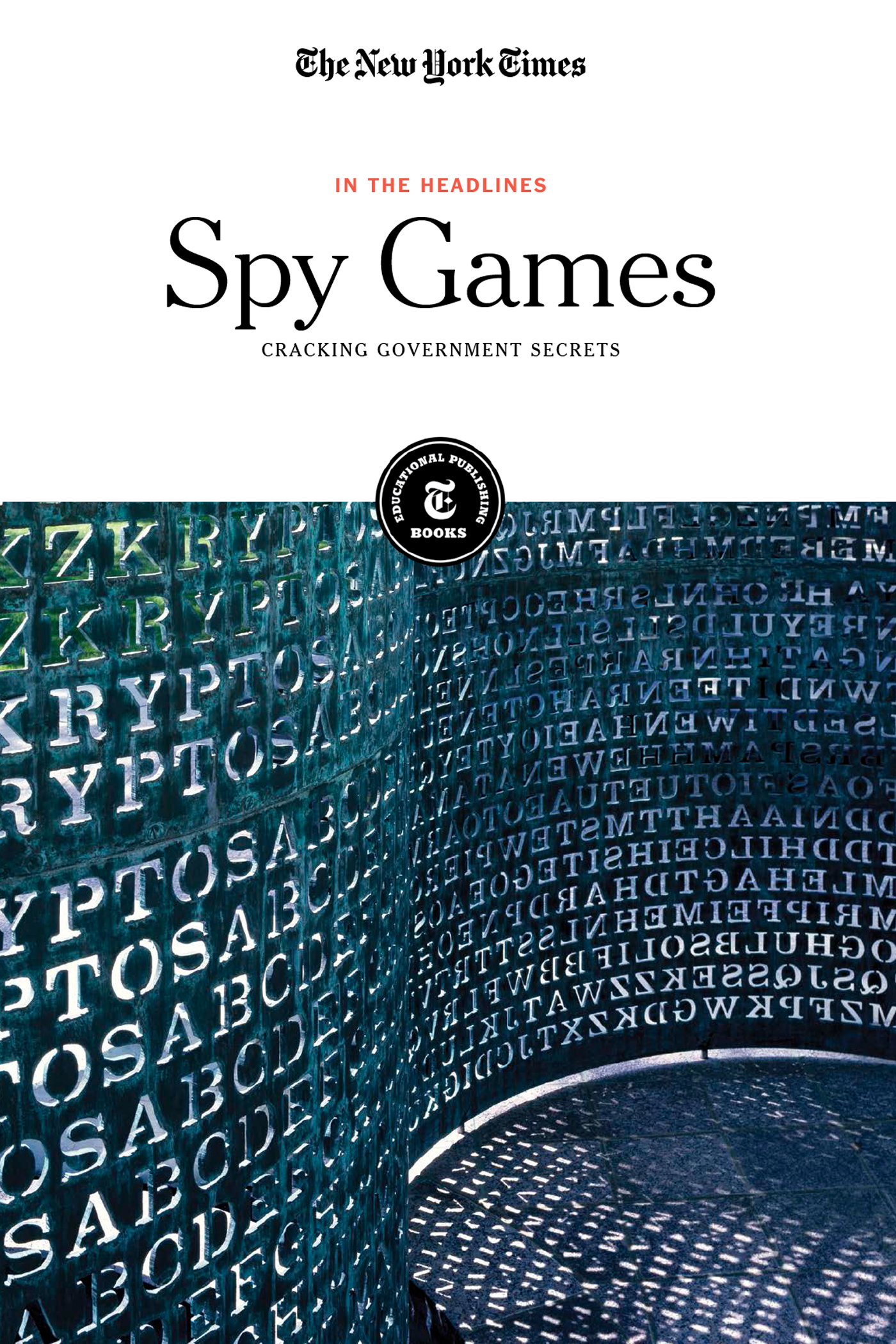

On the cover : Kryptos is a sculpture made out of code. It sits on the grounds of the C.I.A. headquarters in Virginia; Carol M. Highsmith/Buyenlarge/Getty Images.

Contents

Introduction

WHENEVER PEOPLE HAVE interests or goals at odds with others, secrets abound. Where there are secrets, there are inevitably spies who seek them out for their own benefit, whether that is for their own country or group, or just their own wallets. Espionage is, by its very nature, dangerous. That may be part of its appeal to thrill seekers and consumers of spy novels and movies, but throughout the centuries spies have often paid for their activities with their lives.

Wars between and within nations are the most obvious users of spies. Before the instant communication provided by todays cell phones and internet, it could take days or even months to relay information about troop movements, battle outcomes, executive decisions and more to the military. The Civil War period demonstrated how useful spies could be for these purposes and for the sabotaging of enemy forces. The devastating loss of life incurred by both sides during the Civil War may have made government officials and military commanders quick to execute suspected spies. Other significant wars also saw an upsurge in spy activity: World War I, World War II and the decades-long struggle known as the Cold War. Notable figures such as Mata Hari and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg became notorious as spies.

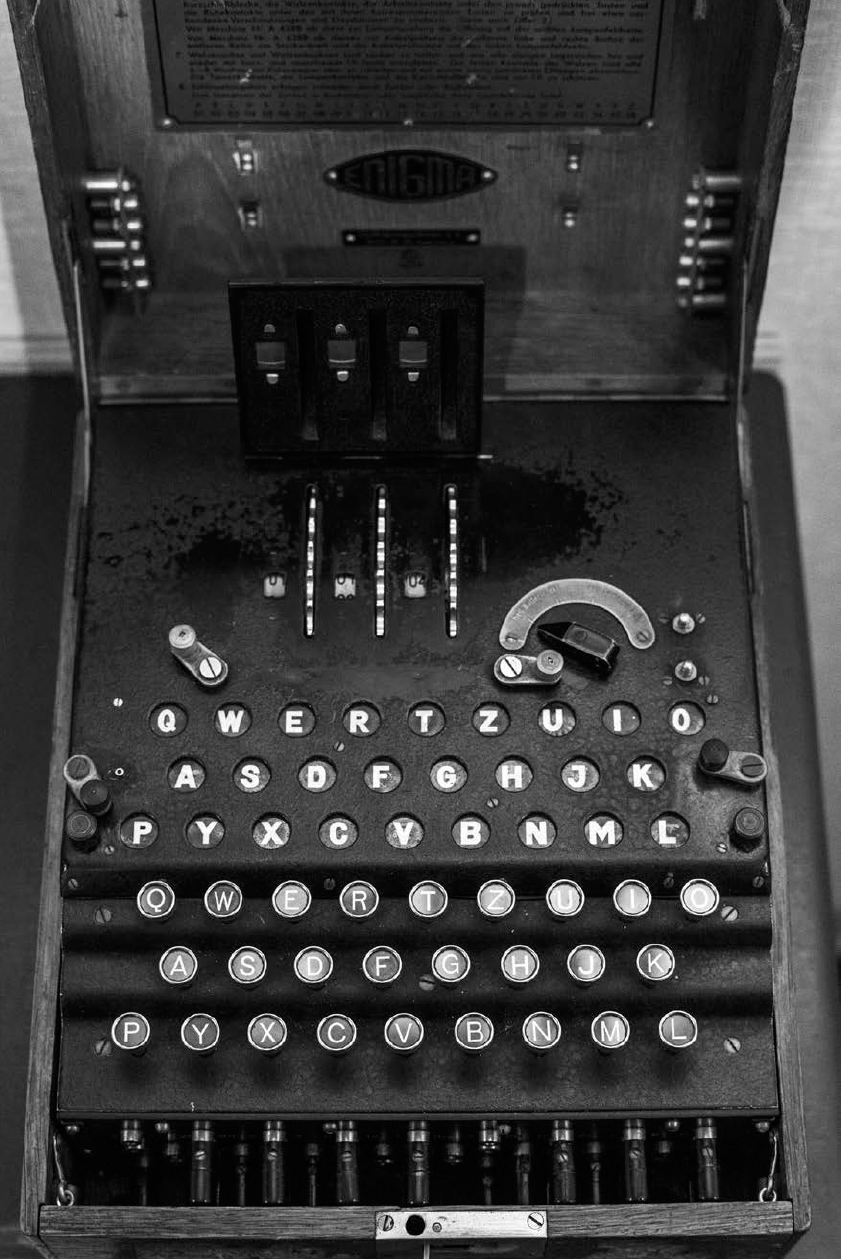

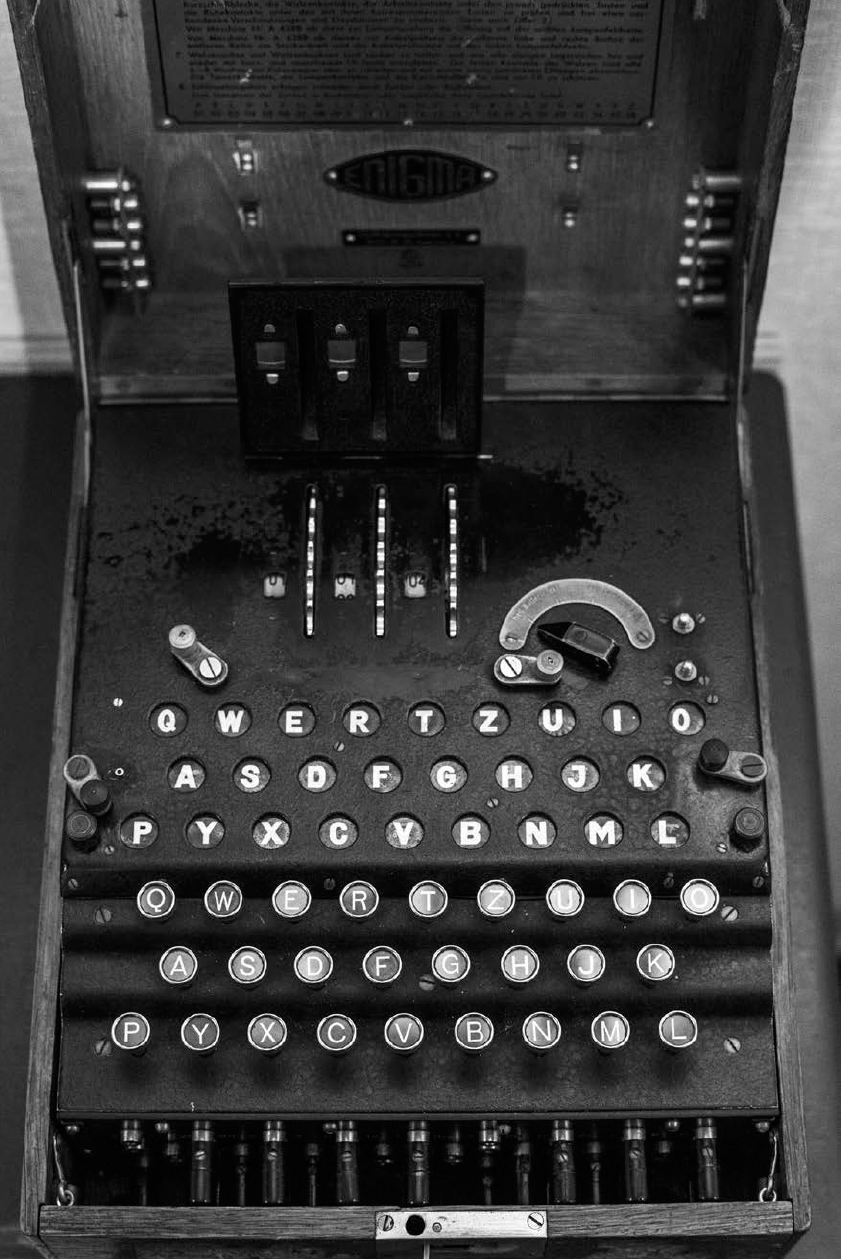

Just as common as the use of spies are the efforts to protect their identities and keep their information secret through disguises and secret codes. Codes can be as simple as handwritten ciphers or as sophisticated as the World War II Enigma machine. During World War II, American intelligence officers made use of the Navajo language to communicate information by code. The language, developed over time by this southwestern U.S. Native American tribe, provided an unbreakable code. The efforts of many code breakers only became known after the wars end.

MATT ROTH FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

The National Cryptologic Museum in Annapolis Junction, Md., has two Enigma machines from Nazi Germany on display.

While war may be the most obvious occupation of spies, it is not the only one. Criminal organizations, crime fighters and political promoters have also used spies and counterspies.

Into the 1960s, the United States efforts to conquer outer space by sending men to the moon and beyond jump-started computer use and technology in previously unimaginable ways. Later, private companies seized on these developments to create internet applications and devices such as cell phones. The use of these powerful new tools opened up new channels for governments to spy on people and for thieves to access the bank accounts and other personal data of many everyday users.

Today, museum exhibitions and book reviews examine the history of espionage and code breaking. Codes and code breaking are an integral part of security, including national security. Newly developed computer tools are being used to keep or break the secrets of governments, including those of the Chinese government, whose interests, both political and economic, are often at odds with those of the United States. In addition, news reports have detailed Russian efforts to interfere in the 2016 U.S. elections, and two former Twitter employees in the United States have been charged with spying for Saudi Arabia. As we continue on into the digital age, the tools and strategies of spies and code breakers alike grow more sophisticated by the day.

CHAPTER 1

1852-1899: War and Foreign Threats

Beset by the Civil War (18611865), this period demonstrates how concerned the country was with spies and saboteurs. Those who were caught often paid with their lives. Codes were sent in secret military communications, and there were reports of a male spy disguising himself as a woman. Domestic espionage remained a public concern even decades after the Civil War ended.

The Inventor of the Code of Army Signals

BY THE NEW YORK TIMES | FEB. 14, 1862

IN A DETAILED DESCRIPTION of the Burnside Expedition, which was given in The Times on Wednesday, a reference was made to the great practical value of the code of signals in use by the army, and the invention was credited to Capt. Myers, of a Pennsylvania regiment of volunteers. This attribution we have since found reason to believe incorrect. It was Mr. Frederick P. Barnard, formerly of Albany, who, after years of painful study, elaborated this very ingenious method by which intercourse, literal in accuracy, can be carried on at great distances, not only by signs visible day and night, but by sounds where the communicating parties are separated by intervening objects, or a fog. Mr. Barnard bears with him vouchers and affidavits of leading citizens of the State, attesting the merit and originality of the invention. It is due to him not only that he should have the praise his ingenuity deserves, but that a more substantial return should be made for his services.

Danger From Spies and Traitors.

THE NEW YORK TIMES | MARCH 2, 1862

FROM THE NASHVILLE UNION, FEB. 12.

OUR CITIZENS ARE WARNED against incendiarism by an incident which occurred yesterday. Cummings Doyle & Co.s pork establishment was yesterday endangered by a quantity of chemical combustibles which was thrown into it while the people were assembled on the public square. Too much vigilance and caution cannot be exercised. There are bad men, spies and Lincolnites in the city, who are ready to do any devilish deed to injure the city and assist their masters. The time for the toleration of even the mildest enemies in our midst has long since ceased. They should be ferreted out and forced to do penance for their disloyalty, or to leave.

The man who welcomes Lincolns hordes is an enemy of the country, and should be recognized and punished as such. He is the personal foe of every honest man and patriot.

Next page