Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing

in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen

Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed

exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Michael Hessel-Mial: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Casualties of war / edited by the New York Times editorial staff. Description: New York: The New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823035 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823028 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823042 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Civilian war casualtiesJuvenile literature. | Civilians in warJuvenile literature. | WarMoral and ethical aspectsJuvenile literature. | Military history, Modern20th centuryCase studiesJuvenile literature. | Military history, Modern21st centuryCase studiesJuvenile literature. Classification: LCC U21.2 C378 2020 | DDC 363.3498dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

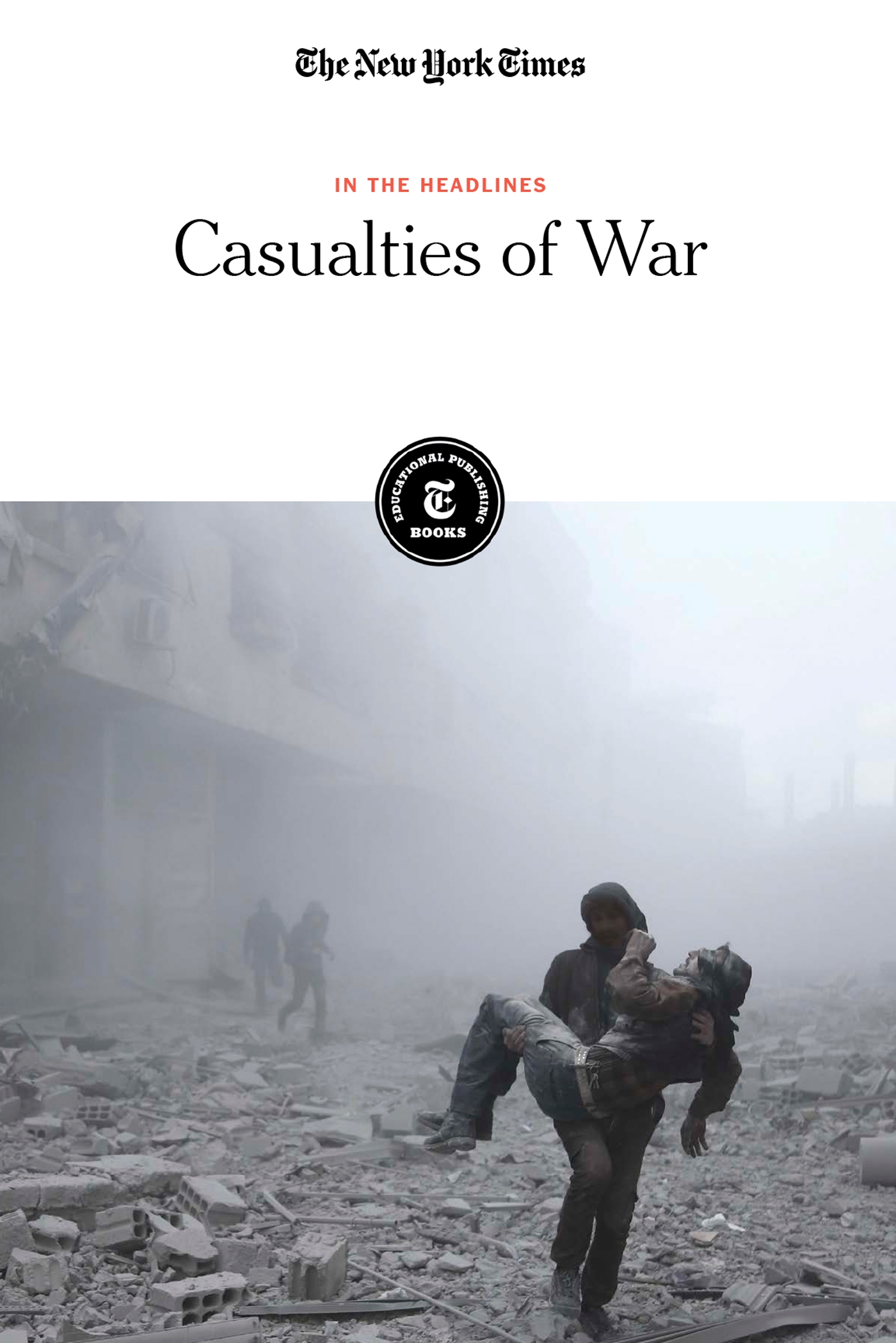

On the cover: A wounded man is carried following an airstrike in Syria on the rebel-held besieged town of Arbin, in the eastern Ghouta region on the outskirts of the capital Damascus, Jan. 2, 2018; Abdulmonam Eassa/AFP/Getty Images.

Contents

Introduction

CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ famously called war politics by other means, implying that war is a tool, a necessary evil to advance a goal. In addition, war is easy to romanticize. We imagine acts of heroism in movies, tactical brilliance in history books, a skillful sequence of kills in a video game and only occasionally the large, unfortunate numbers that accompany them: the victims. In the end, the victims pay wars ultimate price.

The traditional picture of war, where professional armies contend on an empty battlefield, has been replaced by unconventional warfare. In this model of war, high-tech militaries and low-tech guerrillas battle right where civilians live, in the crosshairs.

There are dozens of armed conflicts taking place at this very moment. These wars may seem distant even though the United States and other powerful nations play a strong role in them. To grasp the real effects of war, it is necessary to turn to the victims. By focusing on them, we gain a stronger understanding of wars systematic destruction. War invariably exposes civilians to the threat of mass killings, torture, rape, famine, disease and displacement. Even democratic nations with professional volunteer armies are capable of committing atrocities, as the articles in this collection show.

A challenge to war reporting is that there are significant barriers to fact-finding. Battle sites can be off-limits to reporters, and military policies are often not shared with the public. Even finding the number of casualties is a challenge, let alone determining if war crimes have been committed. Often, unsubstantiated reports are confirmed only years later. As a result, carefully following the complex lines of reporting is essential to uncovering atrocities as they take place.

Wars economic impact creates additional victims. Fundamentally, war disrupts the ordinary workings of peoples lives, leading to crises that would be preventable in peacetime. Blocked grain transportation, a contaminated water supply or the collapse of public services can easily add famine or disease to a wars horrors. Today, most humanitarian crises occur when military conflict causes such disruptions. Such devastation is often the result of deliberate policy, as in the case of Saudi Arabias war against Yemen.

As conflicts unfold, civilian lives are further disrupted by twin problems that affect freedom of movement: displacement and occupation. Most visible to us is displacement. Recent conflicts in the Middle East have led to millions of refugees seeking asylum elsewhere in the world. A look back at the history of war shows us just how common this phenomenon can be. But behind displacement is the threat to peoples livelihoods that comes from long-term military occupations.

Years after the last shot has been fired, survivors of war remain haunted by what they have experienced. However, survivors have often led in building institutions that help countries prevent or recover from the horrors of war. After a series of devastating conflicts in the 1990s, many organizations improved their responses to war crimes and humanitarian crises. Mostly powerfully, Rwanda, devastated by a genocidal civil war, developed a new grassroots model of national reconciliation. Rwandas grassroots justice system helped victims of genocide nonviolently pursue justice against perpetrators, person to person, and rebuild the social trust that was shattered during wartime.

In Gandhis writings, he observes that while history is defined by war, the long-term survival of humanity has always depended on its tools for mutual coexistence. While the worlds conflicts are unlikely to suddenly end, these articles remind us of the choices we can make in how we wage war. Armies can limit the incidence of abuse, just as they can choose not to exacerbate famines. People can support international institutions that promote diplomacy and rules of conduct. And most importantly, governments can choose not to escalate a conflict. Such long-term thinking may one day help us imagine a world without war.

ASHLEY GILBERTSON FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

People lined up for food rations being distributed under military watch in Mainok village in Borno State, Nigeria, Feb. 11, 2017. Dozens of cases of rape, sexual violence and sexual exploitation carried out by guards, camp officials, security officers and members of civilian vigilante groups were reported in Borno State in 2016.

CHAPTER 1

Rich Nations Pursue War at a Distance

Although the United States is currently using military force in a number of countries, most Americans remain unaffected at home. This distance is partly due to the changing character of war, as the use of airstrikes and special forces has become more common. Other wealthy nations, allies and enemies alike, share this tendency to wage war from afar. In addition, the United States and other nations boast significant arms sales, making these distant wars considerably profitable. The cumulative effect has been to make the scope of casualties invisible to the American public.

Drones and the Democracy Disconnect

OPINION | BY FIRMIN DEBRABANDER | SEPT. 14, 2014

WITH PRESIDENT OBAMAS announcement that we will open a new battlefront in yet another Middle Eastern country in Syria, against ISIS (the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria) there is widespread acknowledgment that it will be a protracted, complex, perhaps even messy campaign, with many unforeseeable consequences along the way. The president has said we will put no boots on the ground in Syria; he is wary of simply flooding allies on the ground with arms, for fear that they will fall into the wrong hands as they already have. Obama wants to strike against ISIS in a part of Syria that is currently outside the authority of the Syrian government, which the president has accused of war crimes, and is thus, in our eyes, a legal no-mans land. He has also made clear that he is ready to go it alone in directing attacks on ISIS he has asked for Congresss support, but is not seeking their authorization. All these signs point to drones playing a prominent role in this new war in Syria.

Next page