AFFECTIVE IMAGES

AFFECTIVE IMAGES

POST-APARTHEID DOCUMENTARY PERSPECTIVES

MARIETTA KESTING

Cover image courtesy of the author.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2017 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Eileen Nizer

Marketing, Fran Keneston

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Kesting, Marietta.

Title: Affective images: Post-apartheid Documentary Perspectives / Marietta Kesting.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781438467856 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438467863 (ebook)

Further information is available at the Library of Congress.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this book was undertaken while I was part of the research group Gender as a Category of Knowledge at Humboldt-University, Berlin, and it would not have been possible without the support and resources I found there.

In the final phase Beth Boulokos and Rafael Chaiken of SUNY Press have advised me on all issues ranging from the practical to the conceptual, and I am deeply thankful for that.

Moreover, three anonymous peer reviewers have read my manuscript and offered detailed and thoughtful suggestions for changes and edits that the book benefited from immensely and that widened its scope.

A big thank you to the Hasselblad Foundation and the Ernest Cole Family Fund as well as the South African History Archive, UWC Robben Island Museum Mayibuye Archive, and to all other photographers and filmmakers, who have allowed me to publish their work.

While it is impossible to name all of those who have helped me with their discussions and insights or by their reading more or less developed drafts of this book, I want to thank particularly Christina von Braun, Gabriele Dietze, Claudia Bruns, Alisa Lebow, Julia Schoen, Katrin Kppert, Kirstin Mertlitsch, Nana Adusei-Poku, Todd Sekuler, Kthe von Bose, Aljoscha Weskott, Ole Graf, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrom, Rangoato Hlasane, Darryl Els, Ulrike Kistner, Steven Brimelow, Avital Nates, Terry Kurgan, Michelle Monareng, Caroline Kihato, Loren Landau, Martin Ebner, Nanna Heidenreich, Diedrich Diederichsen, Daniel Hendrickson, Henriette Gunkel, Ulrike Auga, and Sophia Kunze.

In addition, Helga Kesting-Rathmann, Herwig Rathmann, Frank Drwaldt and Dagmar Wei, Gerhard and Anne Wei, and Wolfgang Kesting have provided support in innumerable ways.

Parts of chapter 4 have been published in the essay Photographic Portraits of Migrants in South Africa in Social Dynamics. A Journal African Studies , vol. 40, (Cape Town: Taylor and Francis) 2014, 471494, and are reprinted with permission.

Introduction

A Burning Lens Magnifying Burning Pass Books

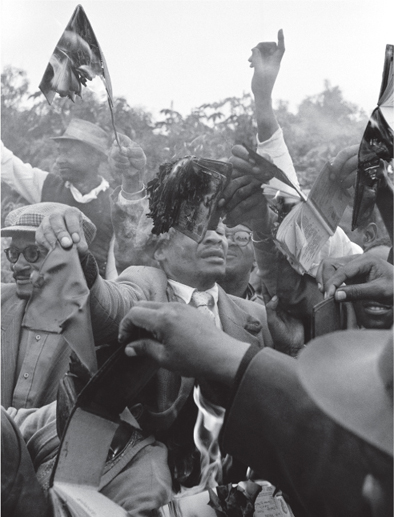

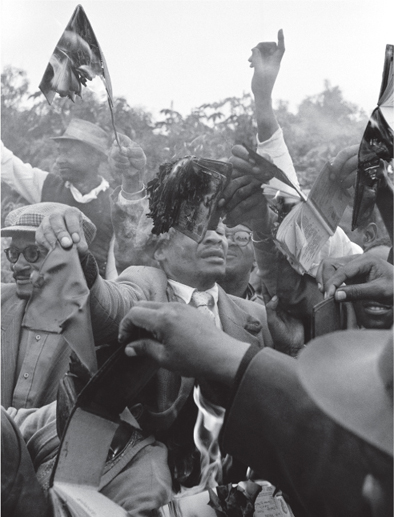

Figure 0.1. A pass burning demonstration, Soweto, SA, 1961, Magnum Photos, Ian Berry.

Looking at a black-and-white photograph from 1961 in the Magnum Photos Archive. It shows the scene of a pass-burning demonstration in Soweto, South Africa. Only black men are visible in it, dressed formally in shirts and ties. The image is confusing at first glance, as hands holding half or completely burnt pass books protrude into the photo from all sides, often blocking out parts of the mens faces.

The photographer composed the image in such a way that in its very center a dramatically charcoaled and frayed piece of a pass book is visible, thereby making this object the main focus of attention for the viewer. The photograph is in vertical format; this is uncommon for photographing events like a demonstration, which are usually shown in landscape format. Here it may have been used to concentrate the action and underline the vertical lines of the hands and fingers, one of which is pointing up to the sky. This visual composition adds force to the scene, it looks like a theatrical staging. Wafting smoke from the burning passes further obscures the image, and flames are visible in the lower part. The men hold the pass books gingerly, as if not wanting to burn their hands, and also because the pass books were hated, despised objects.

The photograph taken with a burning lens acts as a magnifying glass, by focusing on four relevant and problematic issues this study is concerned with. First, when official identity documents with passport photos are obliterated, racialized subjects render themselves unidentifiable, severing the connection between a body and a document, which had restricted this bodys very movement and opportunities in life.

Second, the act of destroying an official photo, which is at the same time a self-portrait, is a reflective political act, since it is an effective and affective performance. As image theorist W. T. J. Mitchell has argued, images may become imbued with a particular agency not merely as sentient creatures that can feel pain and pleasure but as responsible and responsive social beings. Images of this sort seem to look back at us, to speak to us, even to be capable of suffering harm or of magically transmitting harm when violence is done to them.

Third, it is striking that a privileged white male photographer has captured this image of the marginalized black others while they are in the process of becoming officially invisible or undocumented, highlighting the inherent contradictions in the discourse of in/visibilities and (political) self-representation. The white skin of the photographer also seems to render him invisible and unmarked in his privileged male subjectivity and to make him immune to apartheid police persecution. And yet, one must assume that the presence of the white photographer was welcomed by the pass-burners, since the documentation of their action advanced the publicity and was useful for further mobilization.

Fourth, neither is the photographer female nor are there any other women in front of the lens, which points to a blind spot or missing image, since female black South Africans were equal if not the prime protagonists in the protests against the pass laws. These are four conflicting and ambiguous conditions that have to be negotiated when analyzing affective images of post-apartheid. I want to examine and foreground the connection between politics and affect that are prevalent when making documentary films and photography about injustice, violence, and resistance.

As South African historian Patricia Hayes has demonstrated, progressive documentary photography and the discipline of social history or a History from Below developed in South Africa hand in hand. Both disciplines naturalized similar conventions: the one to end silence, and the other to end invisibility.

Figure 0.1. A pass burning demonstration, Soweto, SA, 1961, Magnum Photos, Ian Berry.

Figure 0.1. A pass burning demonstration, Soweto, SA, 1961, Magnum Photos, Ian Berry.