Synopsis:

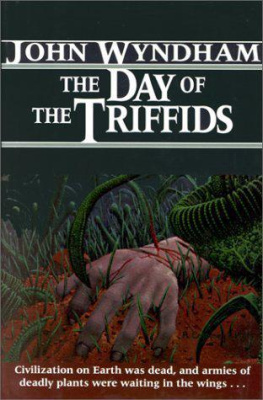

At the end of THE DAY OF THE TRIFFIDS, the hero, Bill Masen, his wife and four-year-old son leave the British mainland to join a new colony on the Isle of Wight. This tiny community, temporarily safe in its island fortress, begins its work not only to eradicate the triffid menace but also to lay the foundations for a new civilization. THE NIGHT OF THE TRIFFIDS takes up the story twenty-five years later. David Masen, the now grown-up son of Bill, is a pilot, still searching for a method of destroying the implacable triffid plant as it continues its worldwide march, seemingly intent on wiping out humankind. David eventually manages to reach New York, where a very different sort of colony has been set up, a colony whose members seem to be immune to the triffid string and where David comes face to face with an old enemy from his father's past.

Simon Clark writes:

I was twelve years old when I discovered John Wyndham's awe-inspiring Day of the Triffids. For me, standing between the world of childhood and the mysterious new world of adulthood, it was a revelation.

The Day of the Triffids wasn't merely a good story; it was such a powerful transforming experience that the hero's struggle for survival has stayed with me ever since.

And yet always, always, when I re-read this great book, I feel an aching sense of loss as I reach the end. The characters were leaving me. But deep down I knew their stories continued. For years I dreamed about their future adventures.

Now, at long last, I can slip into the hero's shoes to explore the ruins of a great civilization which died just a few years before the birth of rock and roll, moon landings and colour TV. I can face the menace of the murderous triffid again and learn that the battle for humankind's survival is far from over.

Writing this book was a real labour of love, and I dedicate it with true respect and admiration to John Wyndham, 19031969

THE NIGHT OF THE

TRIFFIDS

By

Simon Clark

Copyright 2001 Simon Clark and The John Wyndham Estate Trust

To the memory of John Wyndham (19031969)

PROLOGUE

IT is now twenty-five years since three hundred men, women and children withdrew from the British mainland to establish a colony of survivors on the Isle of Wight.

There, in every library and in every school, is a mimeographed typescript of William Masen's account of the Great Blinding, the coming of the triffids and the fall of civilization.

Comprising little more than two hundred quarto pages, it is bound between covers of stiff orange card. Inside you will find no illustrations and not so much as a single photograph.

It is a vivid enough story nonetheless.

This is the final paragraph of William Masen's book: So we must regard the task ahead as ours alone. We think now that we can see the way, but there is still a lot of work and research to be done before the day when we, or our children, or their children, will cross the narrow straits on the great crusade to drive the triffids back and back with ceaseless destruction until we have wiped the last one of them from the face of the land that they have usurped.

That is the end of William Masen's testament. What follows now is the beginning of another in a world that still lies in thrall to the dreadful triffid

CHAPTER ONE

World Darkening

WHEN nine o'clock on a summer's morning appears, so far as your eyes can tell, as dark as midnight in the very depths of winter, then there is something very seriously wrong somewhere.

It was one of those mornings when I awoke instantly alert, refreshed and ready for a new day. I was, as my mother Josella Masen would have put it, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed.

Only, for the life of me, I didn't know why I felt that way. Raising myself onto one elbow, I looked round the bedroom. It wasn't just dark. That's too tame a word for it. There was an absolute absence of light. I saw nothing. Not a glimmer of starlight through the window. No lamplight from a house across the way. Not even my hand in front of my face. Nothing.

Only darkness in its inky totality.

There, I remember telling myself firmly, it's still the middle of the night. You've been woken by some cat giving voice while following its natural instincts. Or perhaps the old man in the next room had to get up for some reason. Now, go back to sleep.

I lay flat on my back and closed my eyes.

But something was wrong. A mental alarm bell jangled faintly yet with some urgency deep inside my head.

I opened my eyes. Still I saw nothing.

I listened suspiciously, with all the intensity of a householder hearing a floorboard creak beneath an intruder's stealthy foot.

Now I was certain that it was the middle of the night; there could be no doubting the evidence of my eyes. I couldn't see even the faintest glimmer of dawn beginning to filter through the curtained window. Yet at that moment understanding at last dawned on me: the sounds I could hear were those of a summer's morning, when the sun should have been streaming across the island's fields.

I heard the clip-clop of a horse passing the cottage, then the brisk rap of a stick on the pavement as one of the Blind went about their business. There came the clatter of front doors. Water rushed down a drain. And, perhaps most noticeable of all, there was the wonderful sizzle of bacon being fried for breakfast, accompanied by its tantalizing wafting aroma.

Immediately my stomach rumbled hungrily. But with those first pangs of hunger I realized that the world, somehow, had gone all wrong. Profoundly wrong.

This was the moment when my life, as I had known it for the last twenty-nine years, ended. Right there, on that Wednesday, 28 May. Nothing would ever be the same again. There was no tolling of a funeral bell to mark its passing. Only the sounds that should not be indeed, could not be! those morning sounds so strangely out of place here in the dark heart of the night: the sound of a horse pulling a cart to the beach; the smart tap of sticks as the Blind went up the hill to the Mother House; the sound of a man's cheery goodbye to his wife as he set out for his day's work.

I lay there hearing it all perfectly. But, I confess, none of it made sense. I stared up at the ceiling. I stared for a full five minutes five seemingly endless minutes

in the hope that my eyes would adjust to the gloom.

But no.

Nothing.

It remained as dark as if I'd been sealed into a box and buried deep underground.

I felt uneasy now. And within seconds that uneasiness spread like the very devil of an itch across my body, until soon I could lie there no longer. Quickly, I sat up and swung my feet out of bed onto cool linoleum.

Now, I was not at all familiar with the room, unsure even of in which direction the door lay. Sheer fate had placed me there. I'd been taking a flying boat on a short hop from Shanklin across the four-mile stretch of sparkling sea to Lymington on the mainland where I was to pick up a foraging party.

I'd been flying the single-engine plane solo those little hops from the island to the mainland were no more dramatic than a local cart journey after all these years.

The sky was clear, the sea flat calm, mirroring that flawless blue; my spirits were high with the prospect of a trouble-free flight on such a perfect summer's day.

However, fate always lies in wait to trip the complacent, with results that are either comic, irritating or lethal.

The instant I overflew the Isle of Wight coast a large gull exchanged its earthly existence for the chance of some avian paradise by the simple expedient of flying into my aircraft's one and only propeller. Immediately the wooden blade shattered.

And a flying boat without its propeller is about as airworthy as a brick.

Luckily I managed to tug the nose of the aircraft round in a U-turn as it glided downward, the slipstream whistling through the wing struts.

Next page