Contents

Its a crucial moment in history. Its an opportunity to immutably and absolutely change the course of innumerable lives.

Arif Naqvi, a silver-haired man of soft bearish charm, was giving the biggest speech of his life. Hundreds of business leaders were gathered at the Mandarin Oriental hotel by New Yorks Central Park to hear him speak on that sunny Monday morning in September 2017. This was his moment. The eyes of the global elite were fixed on him and he knew he needed to make a big impression.

The New York Times and Forbes had published glowing articles about the tycoon, who socialized with billionaires, royalty, and politicians. Among his associates were Bill Gates, Prince Charles, and John Kerry, the former American secretary of state. Arif was a member of powerful boards at the United Nations and Interpol, the international police agency.

It was no coincidence that world political leaders were meeting at the same time a short walk away at United Nations headquarters. For Arifs objective was to convince his audience that he could solve humanitys biggest problemshunger, sickness, illiteracy, climate change, and power shortagesbetter than the politicians assembled across town.

Arif was one of the worlds leading impact investors, and his purpose was to do good and make profitfor his investors and for himself.

Two years earlier, the United Nations had announced a hugely ambitious plan, which Pope Francis blessed, to end global poverty by 2030. The plan required $2.5 trillion of annual funding in addition to what governments and companies were already providing.

Arif said he could help.

He was founder and chief executive of the Abraaj Group, a private equity firm based in Dubai. Abraaj managed almost $14 billion and owned stakes in a hundred companies worldwide. Arif was asking investors for $6 billion more, which Abraaj would use to buy and improve companies in poor countries. By doing this he would help the UN end poverty and make profit for himself and his investors too.

To do good does not necessarily mean to compromise returns, Arif said, pacing back and forth upon the stage. It is gratifying that we are having this event on morning one, day one and hour one of the UN General Assembly week. And what I hope is that everybody, when they leave from here at the end of today, are going to spend time influencing their networks and spending the whole of the week forcing people not to talk about wars and pestilence and negativity but actually the positive energy that comes out of focusing on impact investing.

A revolution in finance was needed and Arif was going to lead it. He wasnt just harnessing capitalism to make money for the rich but to end the suffering of the poor as well.

We want to be the beacon and we want others to join us, Arif declared with his calm, reassuring voice. This opportunity is here. It is now. It is for us to take advantage of and it is for all of us to make collectively the world a better place.

The crowd swelled with applause.

It was a masterful performance, but messages stored on the phone Arif carried told a very different story. Six days before the speech, Rafique Lakhani, a deeply religious Muslim employee who was unflinchingly loyal to Arif, had emailed his boss. Rafiques job was to manage Abraajs cash, and he was desperate because the firm had run out of money, he told Arif in the email. There was nothing left to pay for promised investments in hospitals in poor countries, Rafique told him.

Arifs sunny optimism on stage masked a deep chaos. Behind the faade of operating a successful investment company capable of improving billions of lives, Arif was masterminding a global criminal conspiracy. Abraaj didnt have any money left because he had stolen it. Arif had taken more than $780 million from his firm and misused money from investors including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Bank of America, and the U.S., U.K., and French governments.

Now, unbeknown to the audience, Abraaj was on the brink of collapsing with more than $1 billion of debt.

* * *

Arif was the Key Man. This title, which private equity firms give to their most important executives, had even greater significance in Arifs case because he was offering to solve so many of humanitys problems. He was the charismatic leader of Abraaj and his vision was what investors bought into. He was the reason people gave Abraaj money to manage, and he was trusted with billions of dollars. One adoring investor compared him to Tom Cruise in the Mission: Impossible films.

Abraaj was a money machine that had raised a succession of funds to invest in companies and hospitals across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Arif traveled the world in a private jet and on Raasta, his 154-foot superyacht with teak decks and an art deco interior, to do deals with the rich and powerful. He was a fixture at the annual World Economic Forum in the Swiss mountain resort of Davos.

Arifs rise from childhood in Pakistan, a former British colony, to trusted insider of the elite embodied the burst of globalization that began after the Cold War ended. As new forces brought people closer together around the worldfrom the internet to terrorismArif convinced Western investors that he was their expert partner in exploring distant lands.

As global trade intensified at the dawn of the new millennium, Arif realized that he could pitch his dealmaking skills to politicians as well as investors, as a way to do good by spurring developmentall while generating market-beating returns.

In the aftermath of the attacks of September 11, 2001, Arif persuaded Western politicians that he was an ally who could help bring stability to the Middle East by creating jobs in fragile states where terrorism had deep roots.

He was sought out by billionaires and their millennial heirs who enthusiastically adopted the idea of impact investing and the feel-good veneer it gave to the old game of making money.

When Chinas economic expansion breathed new life into countries along the ancient Silk Road trading routes of Asia, Arif guided Western executives to business opportunities in cities they struggled to find on a map.

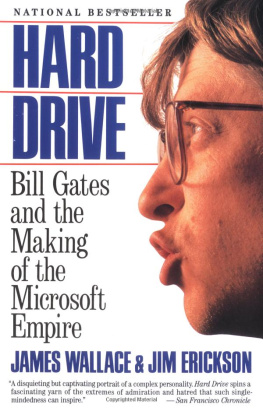

Microsofts founder Bill Gates helped Arif set up a $1 billion fund to improve healthcare in poor countries, and the World Bank and the American, British, and French governments invested in this pioneering fund alongside the Gates Foundation.

Arif won much admiration during his career. A committee of Nobel Prize laureates selected him for an Oslo Business for Peace Award. American academics predicted he might become a brilliant prime minister of Pakistan by 2020 and lead his troubled homeland to prosperity.

As a charismatic, self-made millionaire and one of the most successful emerging market investors, he was well connected, the academics wrote in 2011. Naqvis emphasis on education and self-reliance, along with his self-made personal narrative, untainted reputation and emphasis on fairness and justice resonated well.

* * *

Four months after Arif gave the speech in New York, in January 2018, we received an email from someone who refused to give their name. He or she said they were an Abraaj employee who was afraid that if they spoke publicly theyd lose their job, or maybe worse. They wanted to get a message out and they decided to contact us because we were Wall Street Journal reporters who specialized in writing about private equity firms like Abraaj.

There is a potential fraud investigation, the person wrote. Hundreds of millions of dollars were missing from Abraajs healthcare fund. It is all sad but true.

We exchanged hundreds of emails with the nameless source over the next few months. When we contacted Abraaj, they said the allegations were lies.

Categorically there is no money that disappeared, an American executive at Abraaj said. Why would such a successful firm do something like that?