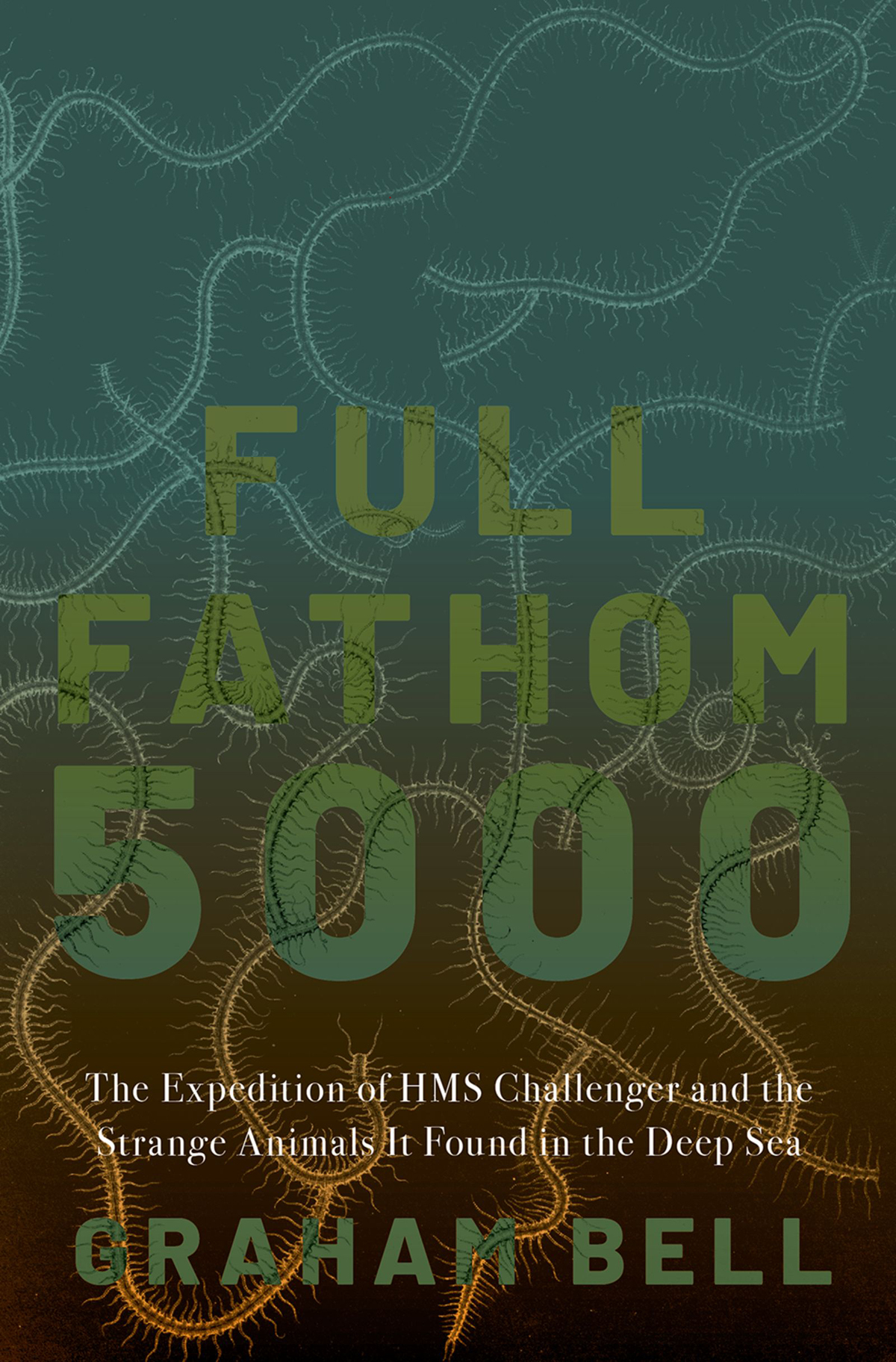

Full Fathom 5000

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Graham Bell 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021044997

ISBN 9780197541579

eISBN 9780197541593

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197541579.001.0001

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 1, Scene 2

For the whole family

Contents

I am extremely grateful for the help given by Lauren Williams and the Rare Books Collection of McGill University in supplying high-quality images from the Reports, which are the basis for the figures in this book. I benefited greatly from visits to the Caird Library of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and the Foyle Reading Room of the Royal Geographical Society in South Kensington.

I have avoided common names for animals wherever possible. The reason is that they are rarely used in common speech. There are exceptions, such as crab and starfish, but who would ever refer in conversation to a comma shrimp or a sea lily? I have instead used the zoological names (cumacean and crinoid, in this case), even though they may be new terms to most readers, on the grounds that any terms will be new and these are exact. It is a little like getting to know the characters in a novel; the names themselves are not important, but you need to know them to understand the plot. I have explained the standard system for naming individual species in the text (Station 106, 25 August 1873). The names of animals sometimes change, however, and the names given in the contemporary Reports may not correspond with those currently accepted; I have taken the World Register of Marine Species (WORMS) as being authoritative.

The most important quantity in the book is depth, which I have given in fathoms, as in the original documents of the voyage. A fathom is six feet, or about two meters. Multiplying the depth in fathoms by two will give you the depth in meters, to an acceptable approximation. Most distances are given in miles, about 1.6 kilometers, or nautical miles, somewhat more; the unit of velocity is the knot, which is one nautical mile per hour or about 1.85 kilometers per hour. Other dimensions, of animals for example, are given in whatever unit seems most appropriate; it may be useful to recollect that one inch is about 25 millimeters and one foot about 30 centimeters. False precision is the enemy of understanding.

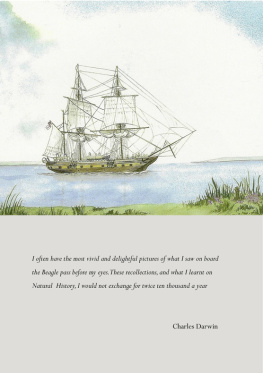

If youre the sort of person who reads introductions (which you are, obviously), I thought you might like to know what this book is about and how it came to be written. I teach biology at McGill University in Montreal, including a rather old-fashioned course on zoology in which I describe all the main groups of animals. Most of these live in the sea. There are plenty of animals on land, of course, but almost all of them are insects or vertebrates, plus a few snails and spiders. Because there are many more different kinds of animal in the sea than on land, I found myself preparing lectures by reading a lot about marine biology, despite not being a proper marine biologist. It was not long before I began to come across references to the voyage of HMS Challenger, back in the 1870s, when many of these animals were collected for the first time. It was obviously a famous affair. The newspapers of the day printed progress reports, and the officers were greeted by royalty, or at least the nearest local equivalent, at many of the ports they visited. All this public attention was because the voyage had a unique objective: it was a scientific expedition to find out what (if anything) lived at the bottom of the deep sea. Nobody knew for sure. Biologists had paddled at the edge of the sea since Aristotle, but anything living deeper than the handle of a net was for all practical purposes out of reach. A few animals were brought up from time to time by fishing gear or ships anchors, but otherwise the only people to visit the bottom of the sea were dead sailors. The first sustained attempts to explore this unknown world were not made until the Industrial Revolution was well under way. When the Challenger expedition sailed in 1873, it was to make the first systematic investigation of what lay beneath the surface of the worlds oceans. Nobody knew what it would find. Anecdotes aside, nobody was sure what covered the sea floor, or what lived there, or even how deep it was. It was the Victorian equivalent of a voyage to the surface of the moon.

The voyage was not particularly eventful, in fact. There were no battles at sea, no shipwrecks, no mutinies to be quelled or pirates to be fought off. It was fairly comfortable, at least by nineteenth-century standards, and the crew were never reduced to eating rats or boiled boot-leather. The scientists on board were very distinguished, but their names and reputations have long since faded into the Victorian mists. There were no women on board at all, no affairs and no scandal. So what is there to write about? Not surprisingly, most of the narrators have chosen to describe at length the time spent on shore, especially the visits to exotic and unfamiliar places, and tend to gloss over the time spent merely sailing from one port to another. Their accounts make very interesting reading as Victorian travelogues, but it seemed to me that something was missingsuch as the main point of the expedition, the animals that it found in the deep sea.

Thats why I began to make notes about the animals that had been discovered during the expedition, and then to trace the voyage on a very large map, and then to scrutinize the species lists for each station, and by then it was too late; at some point it became easier to write the book than not. But why are the animals so important? Well, I suppose that for convenience you might recognize three kinds of animal: there are those you can see, on land and in shallow water; there are those you cant see, because they are too small; and then there are those you cant see because they are hidden from sight in deep water. The first kind is familiar to us all; the second kind was discovered by the early microscopists; and the third kind was discovered by the Challenger expedition. Most of the species captured from the deep sea during the expedition had never been seen before, either by scientists or by anyone else. The expedition did not merely lengthen the catalog of living animals, but, much more than that, added a whole new volume to accommodate the hidden fauna of half the world.