Introduction

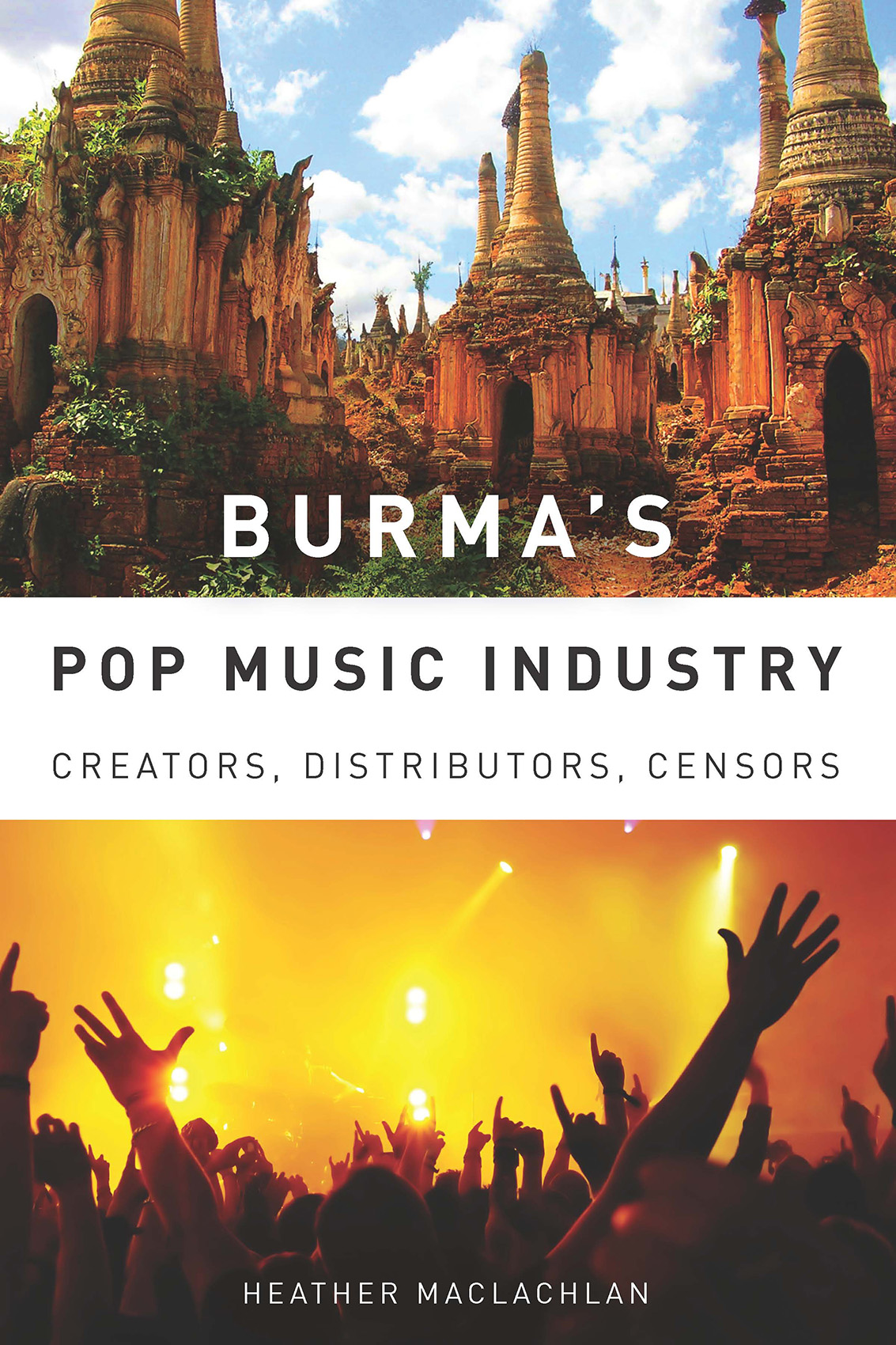

In 1755 King Alaungpaya, the founder of the last great Burmese monarchical dynasty, arrived at the small fishing village of Dagon. At the end of a long campaign to conquer and unify much of what we now know as Burma, he decided to found his new capital. He renamed the location Yan-gon, meaning the end of strife. Standing in modern-day Yangon (also known as Rangoon), it is easy to imagine what Alaungpaya must have seen. Undoubtedly he raised his eyes to the glorious sight of the Shwedagon Pagoda, where devout Buddhists have venerated a shrine containing eight hairs from the head of Gautama Buddha for more than a millennium. He must have seen small family homes made of bamboo, and women carrying their produce to market in baskets balanced on their heads. He would have given alms to saffron-robed monks who wandered the streets at dawn, begging bowls in hand.

It is easy to picture the scene as it looked 250 years ago because, in many ways, the city still resembles the village where Alaungpaya rested. Nowadays, of course, the bamboo huts are interspersed with concrete and steel; there seems to be a new construction project on every major thoroughfare. Cars race past the open-air markets, and monks wear eyeglasses and ride public buses. But glimpses of the older Yangon are everywhere in the contemporary city.

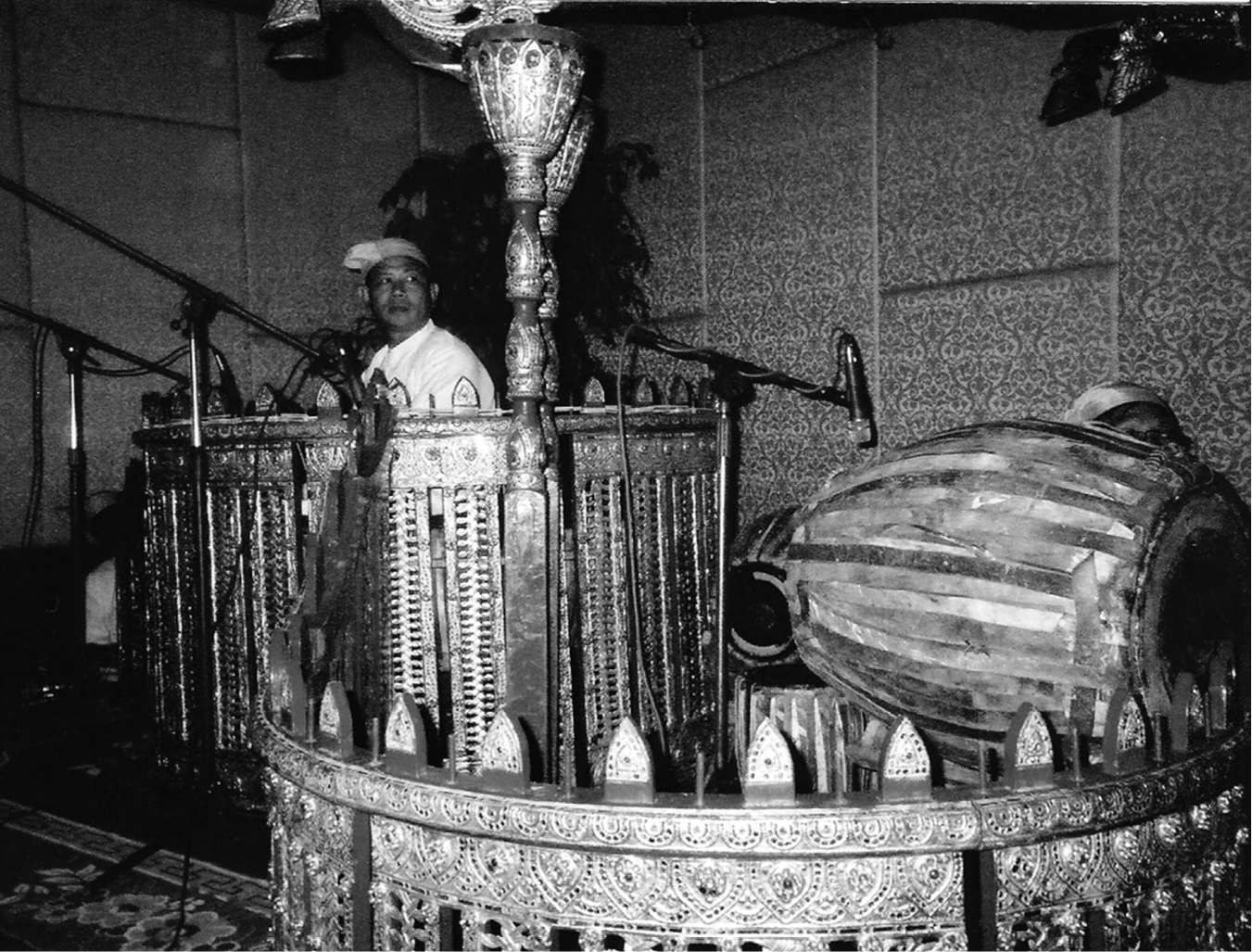

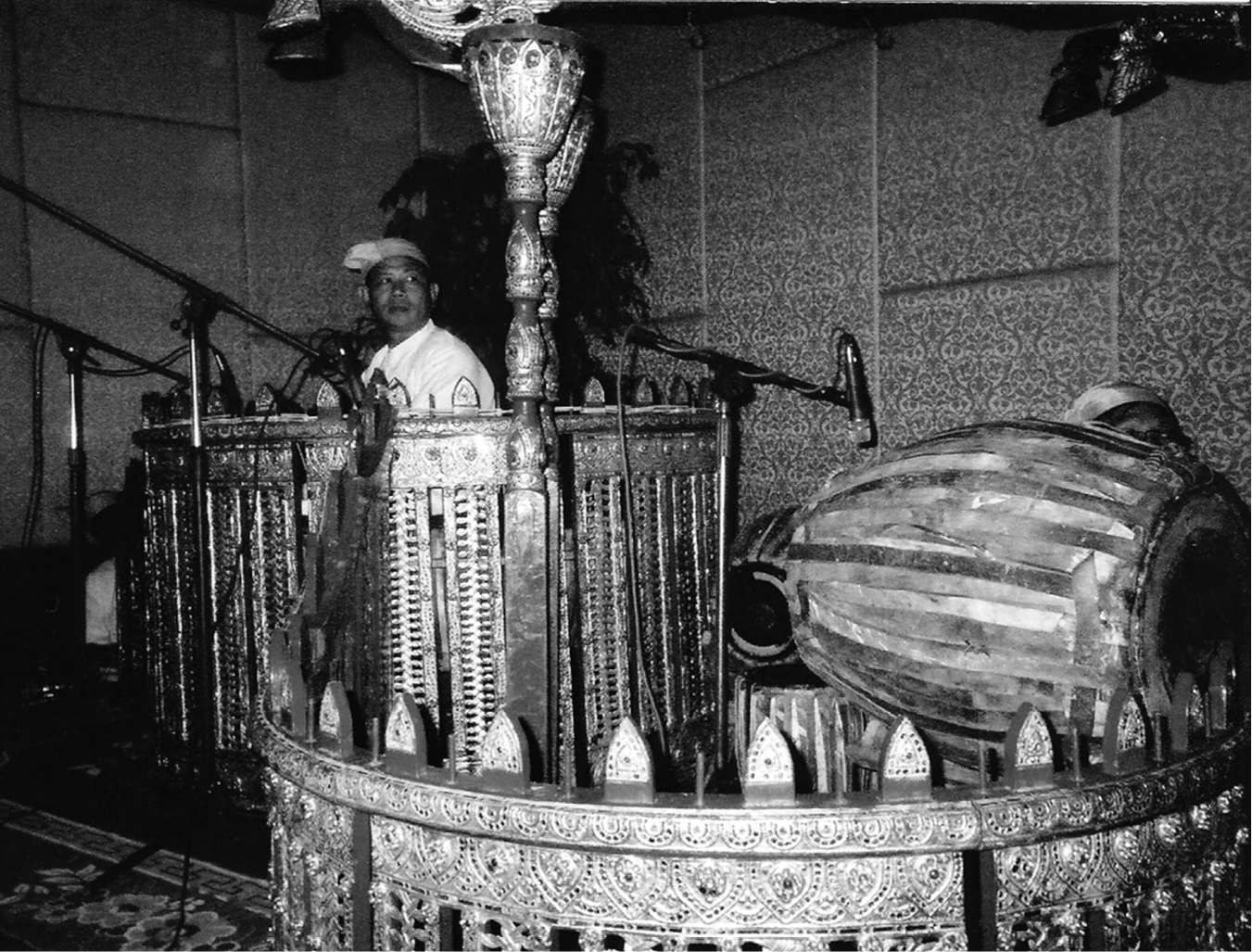

We can still see some of what Alaungpaya saw, and we can still hear some of what he heard. The musical tradition that flourished in the courts of kings like Alaungpaya, known as the Maha Gita, continues to develop today as a vibrant and important part of Burmese life in the twenty-first century. The Maha Gita is a body of song texts written down some centuries ago; the melodies that accompany these texts have been passed down orally. The songs are accompanied by a variety of distinctively Burmese musical instruments, such as the saung gauk (harp) and the pattala (xylophone). The kings mighty instrumental ensemble, known as the hsaing waing, includes a set of pitched drums called the pat waing; tuned gongs; and the hnay, an aerophone with a particularly piercing sound.

From our historical vantage point, we can also hear Burmese musical sounds that Alaungpaya could not have imagined. His dynasty ended, slowly and painfully, as the British colonized Burma in waves of invasion during the nineteenth century. English cultural products, including musical instruments, came to Burma with the colonists, and the resourceful Burmese adopted them for their own use. Through the twentieth century, Burmese musicians developed uniquely Burmese ways of playing the piano, the violin, and the guitar.

Stereo (pronounced sah-TEE-ree-oh) musicians are unabashed admirers of Anglo-American pop music, and stereo aims to fit squarely within the Western pop and rock tradition. The term stereo, however, has become rather dated, and most Burmese people no longer use it. Because of this, and in deference to my English-language readers, in this book I usually refer to stereo as Burmese pop music, which is indeed widely popular in Burma. (The term popular music embraces many musical genres created during the twentieth century, including pop and rock and other genres such as rhythm and blues, disco, country, and soul.) Burmese pop musiclike pop music around the globeconsists of short songs, recorded in a studio and performed live by (usually) solo singers accompanied by the rock instrumentarium: electronically amplified guitars, a drum kit, and a keyboard. These songs are always constructed using tonal harmonies and organized in verse-and-chorus form.

It is important to note that the entire Burmese pop music industry is located in Yangon: virtually all recordings are made in studios in Yangon, and everyone who wishes to make a career in pop music must live in Yangon.

Stereo music is now the dominant music on the airwaves in Yangon, and concerts given by the best-known artists attract thousands of ticket-holders. Photos of the beautiful young singers who perform in these shows appear weekly in tabloid-style journals. Hundreds of people make their livings working in the Yangon-based industry. It is clear that the Burmese pop music scene is increasingly important in Burmese life generally. (Hip-hop, which has exploded in Burma during the past five years, is becoming important as well, but it is unfortunately outside the purview of this book. Hip-hop artists do have some links to the stereo music world in Yangon, but industries are independent of each other.) In this book I will discuss many of the salient aspects of the Burmese pop music scene. For now, it will suffice to make one important point: Burmese pop music cannot be dismissed as just another instance of cultural imperialism.

Cultural imperialism has been a favorite theory of scholars seeking to explain the ubiquity of Anglo-American pop music around the globe.

Pop music scholar Keith Negus argues that whatever else we might say about it, cultural imperialism must be understood as the dominance of certain ownership structures, media technologies, and cultural products in a given market. Following Neguss definition, I argue that the Burmese case cannot be dismissed as a straightforward imposition of American cultural values and products on a vulnerable foreign population. Quite the opposite, in fact: Burmese musicians, until very recently, have gone to great lengths to acquire Western-made recordings, instruments, and recording equipment. These products were not (legally) available in the early days of stereo, and even now must be smuggled into the country in defiance of international sanctions. None of the Big Four oligarchic recording companiesSony Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group and the EMI Grouphas ever had a corporate presence in Burma.

Why, then, the deep attraction to Anglo-American cultural products and to English pop songs in particular? During the colonial era, which lasted until 1947, British overlords promoted all things English to their subject population. They managed to convince at least some Burmese people that the English education system, the English language, and the British way of life were markedly superior to their Burmese analogs. Even today, it is possible to meet self-confident Burmese people (I met some of them during my research) who believe that their own society is somehow lacking in comparison to the West. So we must acknowledge that Burmese people are living with the legacy of an explicit cultural and military imperialism that predisposes some of them to valorize, among other things, Anglo-American pop music.

This aspect of the Burmese pop music scene has led Western journalists to describe the music, and its creators, as little more than the dregs of the American rock and roll movement. Phil Zabriskie, for example, articulated this view in his 2002 Time magazine piece, as did Scott Carrier in a longer piece called Rock the Junta. In the view of these journalists, who usually stay in Yangon for only a few days and who do not speak Burmese, musicians are sad, uncreative figures who do nothing but imitate the great music of the West. Zabriskie describes Zaw Win Htut as a rocker who performs watered-down Burmese covers of rock relics by the Eagles, Rod Stewart and the Beatles and who cannot afford to be... idealistic. And Carrier dismisses the whole city of Yangon with a sniff: While there was a lot of rock and pop music being played all over town, most of it was just awful. Perhaps it seems like tilting at windmills to take issue with these short articles. But this type of literature is virtually all that English-speaking international audiences ever read about Burmese pop musicians; therefore, it is important to scrutinize their accuracy.