Author's Note

Going to Palmyra

Given the distance involved and the expense of getting supplies to Palmyra Atoll, it will always be a hard place to visit. But for the determined traveler, it's possible. For information about how to go to Palmyra, go to http://www.fws.gov/palmyraatoll/visit.html. Whatever the cost in time, energy, or money to travel there, it's worth it. Palmyra Atoll is one of the most spectacular and unique marine wilderness preserves in the world. As such, it is part of the Pacific Remote Islands National Marine Monument, is a jewel in the Nature Conservancy's land rescue efforts, and provides a matchless scientific platform for the universities and institutions that call themselves the Palmyra Atoll Research Consortium.

As for cruising sailors, boats are allowed to anchor in Palmyra's lagoon for one week. Captain and crew can go ashore on Cooper Island only. Potable water is available, but the Nature Conservancy camp, limited in resources, offers no repair help, tool lending, or provisions.

If you want to help the oceans

Throughout this book I've shared the wonder I feel about the marine world, and attempted to show how it saved me during some hard times. Here I get to give back to the ocean by offering ideas about what we can do to help save that precious world.

In the big picture, we have to rebuild our societies in ways that maintain ecological balance. This giant undertaking often feels impossible but humans are an ingenious species, and I believe that scientists and inventors can find practical solutions to worldwide pollution, climate change, over-fishing, and habitat destruction. Concerned citizens can help by supporting environmental legislation and contributing money or skills to research projects, conservation groups, and organizations dedicated to protecting marine wildlife. Here are four I like and trust:

- The Nature Conservancy http://www.nature.org/

- Island Conservation http://www.islandconservation.org/

- Hawaii Audubon Society http://hawaiiaudubon.org/

- The Marine Mammal Center http://www.marinemammalcenter.org/

In the day-to-day picture, adopting small lifestyle changes not only helps the planet but also makes life a little brighter. The following efforts have made me more aware of my consumption, improved my health through exercise, and helped me make new friends:

- Leave the car at home. Run errands by bicycle or on foot.

- Reuse, recycle, and rethink how you consume electricity.

- If you live far from the ocean, visit marine parks and aquariums. Think of the animals there as ambassadors for their species. Let them win your heart and inspire commitment. My lifelong love of sea lions began at a marine park.

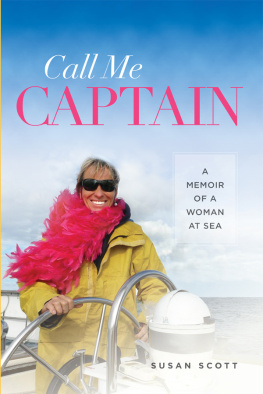

- While walking beaches, carry a bag to pick up trash. This has made me much more aware of our throw-away culture, and also inspired me to make art from marine debris. You can see my art and read my Ocean Watch columns at www.susanscott.net

1

L OOKING down the companionway, I watched Alex remove my husband's foul weather gear in the red night-light of the navigation station below. This was no small task. The storm waves were rolling my thirty-seven-foot sailboat Honu so violently that he had to hang onto an overhead rail and shake his shoulder to remove first one sleeve and then the other. Unclipping the fasteners on the yellow overalls caused them to fall to his knees, and he used his feet to push them from his ankles. Free of the outer clothes, he stretched out on the sea bunk, filling it from end to end.

Alex was tall and slim, sweet and sensitive. He was also twenty-nine years old. Watching him from above like that made me, at fifty-six, feel like a perverted old lady. Was I? Who knew? I didn't know myself any better than I knew the mechanics of the diesel engine beneath my feet. A year earlier an acquaintance posed the question: If you had to describe yourself in one word, what would it be? An uncomfortable silence followed, and as it lengthened, my face flushed hot. I shrugged, embarrassed. I couldn't come up with a single word.

This was our first night offshore, and it was so dark we couldn't see the ocean over the rail. But, oh, we could hear it. Avalanches of water thundered toward the boat like freight trains, their roars getting louder and louder as they raced toward us. Hearing an explosive wave approaching, I would wedge my icy bare feet against the cockpit bench opposite me, grip the steel compass mount as hard as my arthritic hands could hold it, and brace for the hit, only to have the monster smoothly lift the boat and roll beneath. Other times, the gentle whoosh of a small wave would trick me into relaxing, and with a foaming hiss of power, wham. It slammed the hull and sent me flying.

I tightened the Velcro closures of my yellow jacket until I could barely turn my head, but the sea wormed its way in anyway. Occasionally a wave ambushed from an odd angle and struck with such force it felt as if someone had heaved a bucket of water in my face. Salt water dribbled down my cheeks, onto my neck, and into my clothes. Just sitting there was exhausting.

This is the funhouse ride from hell, I said to Alex earlier, when he was still sitting next to me in the cockpit.

I'm getting queasy again, he said.

I looked at my watch. I'll get us another pill. Over our foul weather gear we wore safety harnesses, with leashes clipped to the boat. I freed myself, climbed down the ladder, and worked my way hand over hand across the heaving floor to the medicine cabinet, where I found the anti-nausea medication and swallowed a tablet dry. It tasted salty. Everything tasted salty. By the time I got back to the cockpit to give Alex his scopolamine, I had to clench my teeth to keep from retching.

We sat across from one another in that stiff silence that ensues when people are concentrating on not throwing up and listened to the boat creak and groan in the twelve-foot seas. In preparation for this voyage I had installed a windmill high on the mizzenmast, the secondary mast to the rear of the main mast. The windmill did a fine job of making electricity, but that night in the thirty-mile-per-hour wind it sounded like a maniac was up there with a chainsaw.

Alex flinched, and something hit the deck behind him with a thud. Wow, he said. A seabird flew right past my ear. It came so close I heard it go by.

Kneeling on the bench, we leaned over the cockpit edge as far as our leashes would allow and looked at the deck. There lay a flying fish at least a foot long, its winglike fins flailing, its silver body thumping. Alex snatched the fish and dropped it overboard.

Hey, I wanted to look at that, I said. I've never seen a flying fish that big. I had been the Ocean Watch columnist for the Honolulu Star-Advertiser for twenty-three years and would have liked to examine and write about the fish.

It was suffering, he said.

What could I say? Alex, a University of Hawaii doctoral candidate studying tropical island ecosystems, was the guy I once watched catch a three-inch-long flying cockroach, known as a B-52 in Hawaii, in his bare hands, carry it outside, and set it gently on the ground. It occurred to me as we sat there that the fish could easily have hit him in the eye. I worried about a thousand things regarding this voyage, but never once did I think that Alex might get brained by a fish.

How are you? I said.

Were we crazy to do this? he asked. Or just adventurous?

Next page