RUTH

Ruth

A Migrants Tale

ILANA PARDES

Jewish Lives is a registered trademark of the Leon D. Black Foundation.

Copyright 2022 by Ilana Pardes. All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021950218

ISBN 978-0-300-25507-2 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

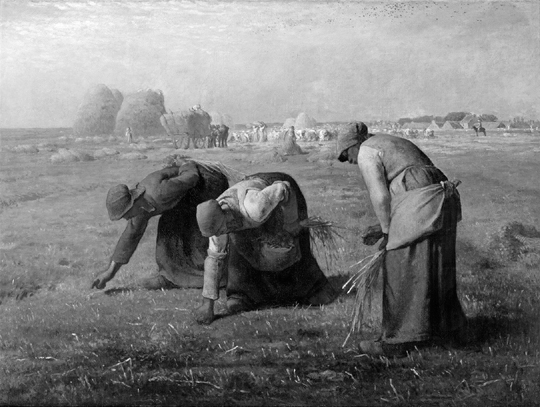

Frontispiece: Jean-Franois Millet, The Gleaners (1857).

Photo Muse dOrsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt.

ALSO BY ILANA PARDES

Countertraditions in the Bible: A Feminist Approach

The Biography of Ancient Israel: National Narratives in the Bible

New Perspectives on Freuds Moses and Monotheism (editor, with Ruth Ginsburg)

Melvilles Bibles

Agnons Moonstruck Lovers: The Song of Songs in Israeli Culture

The Book of Job: Aesthetics, Ethics, Hermeneutics (editor, with Leora Batnitzky)

The Song of Songs: A Biography

Psalms In/On Jerusalem (editor, with Ophir Mnz-Manor)

For Keren and Eyal with love

RUTH

INTRODUCTION

Preliminary Gleanings

T HE BOOK OF R UTH offers the most elaborate tale of a woman to be found in the Bible, but even this relatively detailed account is astonishingly spare. The book of Ruth is not really a book. It is only four chapters longmore of a short story, or a very short story, than a book. To write a biography of Ruth thus means to become a gleaner, to gather bits and pieces from sparse scenes that are replete with lacunae. And yet, despite its ellipses, Ruths cryptic tale is remarkable for its capacity to provide, with but few vignettes, a vibrant portrait of one of the most intriguing characters in the Bible.

The opening note of the book of Ruth is devoted to a packed expository account of the migration of Elimelechs family from the land of Judah to Moab. Much like Abraham and Jacob, who go down to Egypt in times of famine, Elimelech migrates to a foreign land in quest of sustenance. He is accompanied by his wife, Naomi, and their two sons, Mahlon and Chilion. It is a But the narrative does not dwell on Ruths marital life, nor does it reveal anything about her response to the death of her husband. Instead we shift from the prelude to another story of migrationwhere the drama beginsthis time in the opposite direction, from Moab to Bethlehem.

Ruth emerges onstage only on the road between Moab and Bethlehem, after leaving her home and homeland to head to the land of Judah, a land she had not known hitherto. Her migration is as radical as that of Abrahams inaugural move to Canaan but different in character. No God calls out of nowhere and demands that she go forth. Going forth is her own initiative, and her primary objective is not to obey God but rather to stand by Naomi. With remarkable flair, Ruth endorses hesed, kindness, as her guideline, willing to take all the risks involved in following her impoverished, melancholy mother-in-law to a foreign land.

Ruths tale of migration is an unusual one. Elsewhere in the Bible, in the great stories of migration in Genesis and Exodus, male characters are the ones to prevail; here, a woman is set center stage, and the specificities of the life of a female migrant are spelled out with distinct verve. We follow Ruth through the various stages of her migratory life, from the moment she leaves Moab as a childless widow, determined to join Naomi, through the circuitous process of acculturation in Bethlehem, beginning with her struggle to survive as a gleaner in the barley fields and ending with her marriage to a local, Boaz, and her giving birth to Obed.

What makes Ruths migratory tale all the more exceptional is that she is a Moabite. It is the story of a Moabite woman who, on moving to Bethlehem, becomes not only a member of the people of Israel but also the foremother of King David. This dramatic shift in Ruths position is one of the greatest enigmas of her life: How could a foreign woman become a founding figure of the Davidic dynasty? What is her charm? What makes her indispensable?

Ruths tale is set in the days when the judges ruled (Ruth 1:1). The judges, the shoftim, are tribal chieftains who ruled in the pre-monarchic period, presumably from the thirteenth century to the eleventh century BCE. Despite this historical note in the first verse, we might well wonder if Ruth is a historical figure or a figment of the imagination. There are no archaeological findings or extrabiblical texts that corroborate her existence. This lack of evidence, however, does not prove that Ruth never set foot in the fields of Bethlehem. It is hard to imagine any scribe daring to position a Moabite woman at the base of the Davidic dynasty if there were not some basis in historical reality. But whether or not Ruth was a genuine historical figure, the book of Ruth treats her as such. The God of Israel reveals himself in history and carries out his plans through and against real people. A historical impulse informs the Bible, though this impulse surely differs from modern notions of historiography.

History in the Bible goes hand in hand with literature. In fact, narrative is the prevalent mode for recording past events in the biblical text. Features that today would be perceived as the domain of literatureelaborate studies of human relationships, dialogues no one could have heard, inner thoughts, depictions of emotional responsesare regarded in the biblical context as

The association of Ruth with the time of the judges is rather odd since her tale seems to be the antithesis of the representation of this period in the book of Judges. The well-known and recurrent verse of Judges is Every man did what was right in his own eyes. It is an age in which lawlessness and strife prevail. Ad hoc tribal chieftains, the shoftim, attempt to rescue the weak confederation of Hebrew tribes from their enemies, but shortly after each battle, even the most successful ones, chaos returns. With its unique ambience, the book of Ruth offers an alternative human possibility, or, perhaps, a glimpse of a different chapter within this period. We enter Bethlehem in the days of harvest, with no shadow of an enemy on the horizon. People greet one another with respect in the fields, and legal matters are settled peacefully at the towns gate.

There are no villains in the book of Ruth. In fact, one of the tales stunning literary feats is its convincing portrayal of good people. It is a rare world in which hesed emerges as a cherished principle of human relations. Ruth is the primary agent of hesed, and she is hailed for it time and again. But other characters are also construed as kind and compassionate. Even Orpah, who, unlike Ruth, decides to head back to Moab instead of following her mother-in-law to Bethlehem, is not wicked. Naomi thanks Orpah for her hesed and care while urging her to return to her mothers house. She is a good person, just less good than Ruth. God too has a pivotal role in advancing hesed, but he remains behind the scenes. He is not really a character and his voice is not heard. It is primarily human agency and human goodness that shape the drama in the book of Ruth.

Next page