To Nora

ARCHITECTURE

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

PAVLOS LEFAS

Jovis

The Terra Amata Huts

Mesopotamia: The Oval Temple

The Giza Pyramids

Ur: Igmil-Sinss House

The Temple of Amun at Karnak

The Acropolis of Athens

The Great Roman Aqueducts

Inventing Interior Space

Angkor Wat

Medieval Cities and Gothic Cathedrals

The Alhambra

The Forbidden City

The Great Temple of Tenochtitlan

SantAndrea in Mantua

The Rock Garden of Ryan-ji Temple in Kyoto

The Villa Rotonda

The Great Wall of China

The Masjed-e Shah in Isfahan

From Pont Neuf to Vierzehnheiligen

1800: The Grid

Tall Buildings

Modernism

The Age of Motorization

From Vitruvius to Green Architecture

I am grateful to Michael Iliakis who carried the burden of the translation into English, to Sofia Bobou who helped in its initial stages, and to Inez Templeton who edited the text.

I want to thank the following colleagues who helped me avoid some mistakes and misconceptions. They are Hasan Badawi, Panayotis Evangelides, Panagiotes Ioannou, Lilian Karali, Nikos Karapidakis, Yannis Kokkinakis, Eleni Kondyli, Michael Kordosis, Martin Kreeb, Callirroe Palyvou, Stylianos Papalexandropoulos, Qiang Li, Eleni Sakellariou, Gebhard Selz, Panayiotis Tournikiotes, Jonathan Taylor, Dusanka Urem-Kotsou, Lorenzo Verderame.

At the end of each chapter, there are books and papers mentioned, which have directly influenced the authors point of view. A generic bibliography is not given, since it is constantly renewed and complemented with new, important contributions.

This book talks about architecture, about the concerns, the pursuits and the achievements of its people, and about how their work has been perceived.

Just as any other narrative, however, this account is by its very nature unfairnot only because Western architecture is overrepresented in it, but also because it leaves out of the picture thousands and thousands of buildings in which real people were born, brought up, lived, and died. Small jewels, monuments of vanity, or simply ordinaryall were the product of toil and the receptors of dreams; for that reason alone, they do not deserve the oblivion into which they are pushed deeper with each new reference to other, seemingly slightly better, slightly more important, or slightly more celebrated contemporary buildings.

With the unkindness and arrogance associated with our power to choose, to remember, and to forget, this book looks at the past through the lenses of someone whoin the chaotic complexity of the universe of edificesseeks to understand why and how people build.

The past emerges unexpectedly in its proximity. This is probably the best vindication of those who devoted their time and efforts to create day by day, stone by stone, the environment in which we live today.

This book is a guide for reading architecture of yesterday with our eyes focused on tomorrow. It is written with the hope that it will spur the reader to search for other views and to complement his/her knowledge with further reading and the examination of other sources; and to look around him/her once more at the magic of the world surrounding us.

ARE THERE ARCHETYPES IN ARCHITECTURE?

The Terra Amata Huts

Unlike clothes, buildings cannot be squeezed into the back of our closet or taken to the local charity shop when no longer in fashion; they are meant to stay. Not having the chance to design new ones for the upcoming season, architects would like their buildings to withstand the test of time and not be seen as obsolete the day after; owners who pay good money to have the buildings erected expect their investments to have value for as long as possible; and users insist that certain things be done the way they should be done, no matter how fascinated by innovative ideas they might be. This is why the question are there archetypes in architecture? has been central to architectural theory throughout the ages, and still retains, to some extent, its validity. An archetype in architecture is a form that we keep reproducing, more or less deliberately, acknowledging therein an irrefutable wisdom and an appeal that may never perish. Form is used here in the original sense of the term: as the structure, organization or essential character of something, rather than merely its appearance. An archetype, then, is a paradigm that incorporates what is important and perennial, and as such one that can adapt to specific contemporary requirements over changing times, while maintaining all its primary qualities.

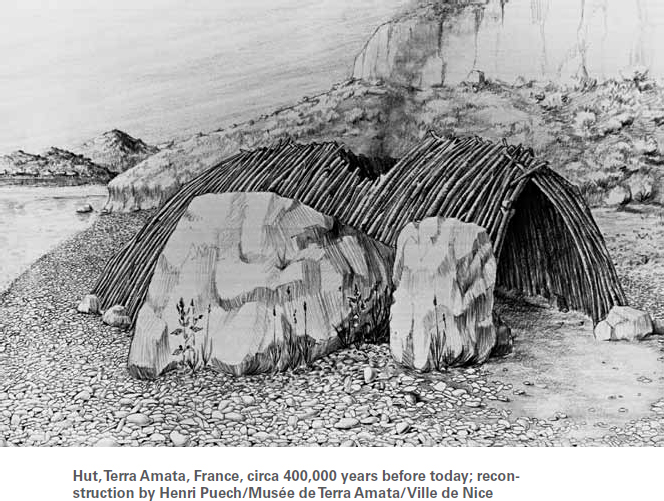

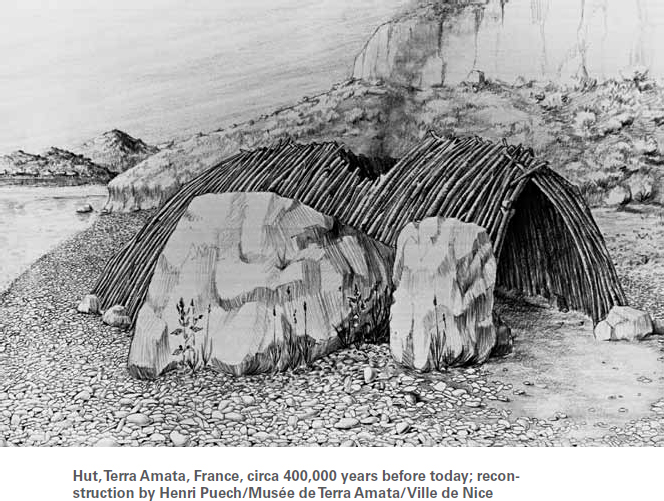

Watching children drawing pictures of their dream homes in the almost stereotypical shape of a small house complete with roof and smoking chimney, one feels as though he/she is witnessing an archetype in architecture. This might well be so. In the remote past, humans evidently used to build huts fairly similar to our own perception of an essential dwelling: the simplest imaginable shelter with a smoking chimney.

In the nineteen-sixties, a team led by Henry de Lumley discovered at the site of Terra Amata in Nice, southern France, vestiges of large huts erected 400,000 years agoalthough other scholars doubt his interpretations completely or date the finds tens of thousands of years later; 400,000 years is a long time. The human species, to which the individuals who built the huts belonged, was extinct long ago. Modern humans came to Europe from Africa about 40,000 years ago. The Parthenon was built 2,500 years ago; Leonardo da Vinci conceived his flying machines 500 years ago; and the first underground railway line began operating in London 150 years ago.

De Lumleys excavations revealed that several meters beneath the current surface of the ground, earth and sand were thinner in texture in some places. He interpreted this as dirt accumulated in holes born by tree branches pinned to the ground; the wood disintegrated over time, but left traces on the walls of the holes, providing further evidence to support his assumptions. The holes, clustered in several groups, were not perpendicular, indicating that the branches converged together forming real roofs. The huts, erected along what would have been the seaside at that timeto offer temporary shelter to humans coming to the area to hunt or fishwere oblong, measuring approximately eight to twelve by four to five meters. At the center of each hut, traces of fire were found; probably at the top an opening was left to let the smoke out. Also uncovered here and there were clusters of similar objectsfragments of stone, animal bones, food remains, etc.suggesting that the space inside each hut had been organized so that different activities (preparing and cooking food, tool making, sleep, etc.) should take place in distinct zones, similarly to modern dwellings.

Traces of a more recent but still very early dwelling150,000 years oldwere discovered inside a cave only a few kilometers away from Terra Amata. At Grotte du Lazaret, a number of large stones circumscribed an area about 11 meters in length and 3.5 meters in width. While outside this area, finds of human activity are scarce, inside they are abundant: numerous bones, stone tools, and stone fragments have been found, as well as two circular charcoal concentrations that researchers have identified as hearths. This suggests that the stones had supported branches propped up against the wall of the cave, and were layered with animal skins, forming a shelter. Fire residue shows that the proportion of slow- to quick-burning logs was considerably higher there than within a radius of several kilometers around the cave.

Next page