AFTERWORD by Kieran Mulvaney

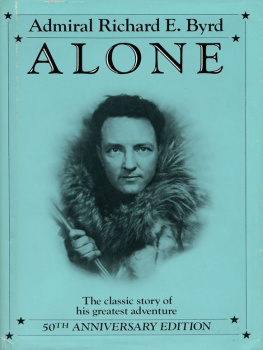

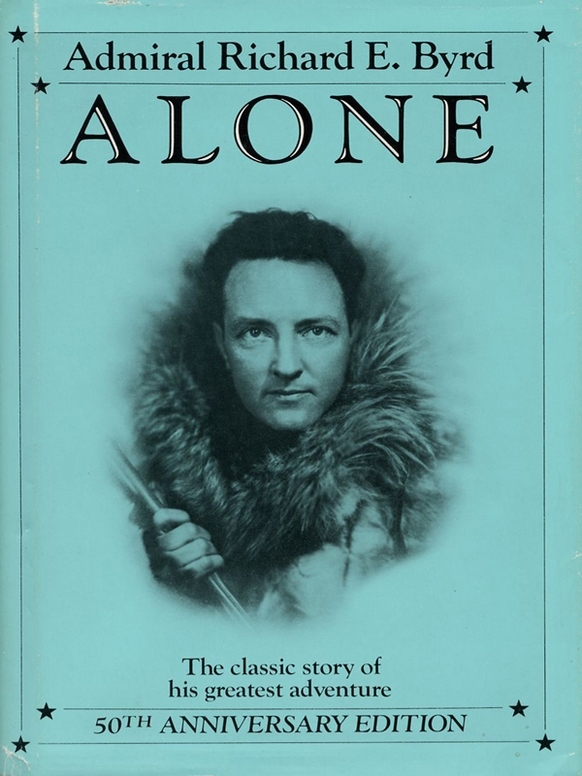

The extraordinary events documented by Richard Byrd in Alone are among the most famed and dramatic in the history of Antarctic exploration. The story of Byrds winter alone on the Ross Ice Shelf stands alongside such celebrated Antarctic sagas as the race between Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott to be the first human being to reach the South Pole, and the remarkable voyage of Ernest Shackleton, whose ship Endurance was crushed in the ice of the Weddell Sea, but whose crew nonetheless survived a harrowing ten-month ordeal that included living on ice floes and making a death-defying lifeboat trip across 800 miles of tempestuous Southern Ocean.

Byrds own brush with death during the Antarctic winter of 1934 was of a different nature than those of his predecessors. Scott and Shackleton fought pitched battles against arguably the most inhospitable environment on Earth, highlighted by daring dashes across vast expanses of snow and ice. Byrds drama, on the other hand, unfolded within the confines of a shack that protected him from the fierce elements outside, but where he was nearly slain by the very device that was meant to keep him warm during the long Antarctic night. After the ordeal, Byrd considered himself a failure, despite spending four and a half months alone, for being unable to last the entire winter by himself and thus for endangering the lives of those who came to rescue him. It would be several years before he could bring himself to write a book about the experience. But the public lapped up the story, and when Alone was published in 1938 it was a best-seller, reprinted frequently in the United States and published in several different languages. Indeed, by the time of its publication, Byrds multiple adventureshis two Antarctic expeditions, two Arctic expeditions, and a nonstop flight across the Atlantichad so inspired the nation that he was among the most admired and famous people in the United States. More than sixty years later, with interest in stories of adventure and exploration in the polar regions seemingly at an all-time high, Alone remains a relevant and inspiring tale of digging deep and finding the personal strength to overcome the odds, however impossible they may appear.

Born on October 25, 1888, to a prominent family in Winchester, Virginia, Richard Evelyn Byrd began his explorers life at an early age, traveling alone to visit his godfather in the Philippines when just twelve years old, and cataloguing his adventures for the Winchester newspaper. A naval career begun a few years later proved brief and relatively unfulfilling, even though Byrd received the Congressional Life-Saving Medal in 1914 for twice rescuing drowning seamen. A series of injuries to his right foot, suffered in athletic pursuits at Annapolis and compounded by falling through an open hatch on the USS Wyoming, hindered him physically, and as a result he was retired from active duty in 1916.

With the closure of one door, however, Byrd opened another when he secured appointment in 1917 as a naval aviation cadet at Pensacola Naval Air Station. Aviation was barely out of its infancythe Wright brothers had flown at Kitty Hawk just fourteen years beforebut progress was rapid. Haphazard frames of wood and canvas were being succeeded by metal bodies powered by increasingly reliable engines, and the development of radio allowed pilots to communicate with the ground. Flying remained an uncertain and extremely risky endeavor, but despite the danger, Byrd reasoned that the objections to having a lame man on board ship would not necessarily apply in the air. My one chance of escape from a life of inaction was to learn to fly, he wrote.

Byrd was never a particularly good pilot. (In fact, several accounts of his extreme nervousness before many flights suggest Byrd may have been terrified of flying, which if true would make his later achievements all the more remarkable.) Instead, he concentrated on navigation, which he taught to young cadets, and he later was posted as a liaison with Congress in Washington, D.C., where he played an important role in the establishment of the U.S. Navys Bureau of Aeronautics and the Naval Air Reserve.

Byrd sought more than the realization of bureaucratic goals, however; he yearned for adventure, discovery, and fame. Observes historian Lisle Rose in Assault on Eternity: Perhaps it was just his own lonely temperament, perhaps the lure and love of flight when every trip aloft took raw courage, perhaps just the flatness of the drab postwar military world of the 1920s, perhaps a combination of all three, but whatever the forces, Richard Byrd began to dream of dramatic explorations and conquests. His early plans, however, met with disappointment, as writer Eugene Rodgers noted in Beyond the Barrier. a request to fly solo across the Atlantic in a navy plane was turned down; a plan to make a similar journey in a dirigible was abandoned when the craft crashed during a test flight; a proposal to explore the Arctic from the air was rejected, and a second proposal along similar lines was approved but then scrubbed.

Frustrated, Byrd elected to put together a private expedition, turning for inspiration to recent explorations of the Arctic regions. The drama and excitement of the race for the North Pole was still fresh in his memory and that of many Americans, a drama that apparently had culminated in 1909 when both Robert Peary and Frederick Cook had claimed to be the first to the North Pole. (Each man spent much time and effort subsequently deriding the others claims, and their respective backers continue to do so; the evidence suggests, however, that both men faked their achievements.) Much of the Arctic remained unexplored in any case, and Byrd was a passionate advocate of aviation as a way to cover vast tracts of the frozen wilderness far more easily and comprehensively than explorers trudging across snow and ice. The dogsledge must give way to the aircraft, he later proclaimed. The old school has passed.

Byrds first foray into the Arctic in 1925 proved to be only a limited success; to proceed, he needed logistical and materiel assistance from the navy, forcing him to subsume his expedition under that of Commander Donald MacMillan, a veteran Arctic explorer to whom the navy had already pledged support. MacMillan and Byrd frequently clashed, and weather conditions limited flying to just fifteen days of the two months the expedition was in Greenland.

Byrd vowed to return in 1926 with another private expedition, with the express intent of reaching the North Pole by air. The first such attempt had been made the previous year, by Norwegian Roald Amundsen (who, using dogsleds, had been the first to reach the South Pole in December 1911) and American Lincoln Ellsworth; they had abandoned their effort when one of their two planes had broken down. Amundsen and Ellsworth were planning their next attempt in a dirigible, the Norge , with Italian Umberto Nobile; Byrd also flirted with the idea of using a dirigible, but then a three-engine Fokker was offered to him at a discount price. The added security of two additional engines, he decided, made the fixed-wing plane the perfect platform for his flight.

Byrd arranged financing from a variety of sources, many of whom would prove regular contributors to his expeditions, including John D. Rockefeller and Edsel Ford (after whose three-year-old daughter, Josephine, Byrd named the airplane). As he would do in the Antarctic, Byrd also arranged deals with the news media, accepting financing from the likes of Path News and the New York Times in exchange for exclusive newsreel and print coverage rights.