ILLUSTRATIONS

FIRST COMMAND

TOM, DICK AND HARRY BYRD

EARLY SEAPLANE

THE BEACH AT PENSACOLA. ALL PLANES ARE SECURED INSIDE THE HANGARS

PENSACOLA, 1918

WORK FOR THE RESCUE BOAT

ANOTHER CRASH

A CRASH OF A TRAINING PLANE AT PENSACOLA, LIFTED CLEAR BY THE WRECKING BARGE

PALSCOMMANDER BYRD AND VIOLET

SUMMER, 1918, HALIFAX AIR STATION

ARTIFICIAL HORIZON SEXTANT

A FAMOUS CRAFT

JUST BEFORE THE DISASTER

LOOKING FOR BODIES

BYRD AND HIS RUBBER RAFT

LAUNCHING OUR AMPHIBIAN

NORTH GREENLAND

WESTWARD

A NATIVE PASSENGER

GREENLAND ICE CAP

A HAZARDOUS UNDERTAKING

STUCK ON THE ICE-FOOT

FILLING THE FUEL TANKS

OFF FOR THE POLE

CAN SHE MAKE IT?

NORTHWARD HO

CHART OF ROUTE FLOWN BY BYRD TO NORTH POLE

THE NORTH POLE

HOME AGAIN!

UP BROADWAY, JUNE, 1926

THE CRASH

TOUGH LUCK, OLD MAN!"

WAITING TO GO

JUST BEFORE THE HOP-OFF

THE Americas LANDING

WRECK OF THE America

AFTER 42 HOURS OF HELL!

BYRD AT PARIS

RECEPTION AT THE INTER-ALLIED CLUB AT PARIS

WAR WOUNDED

A SECOND HOMECOMING

UP BROADWAY

A SOUTH POLAR SEA lCEBERG

COMMANDER BYRD IN ARCTIC FLYING COSTUME

AN HISTORICAL MEETING

AT WASHINGTON

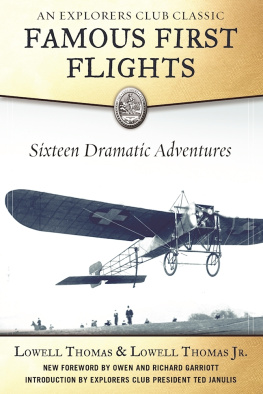

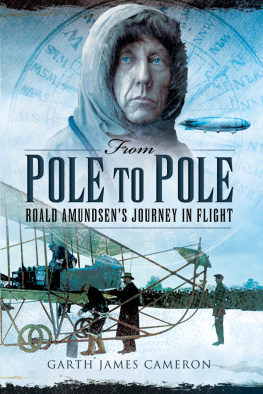

SKYWARD

The author wishes to express his appreciation for permission to include herein material previously published by Colliers, The Ladies Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post.

Parts of Chapters VIII, IX and XII are copyrighted by The National Geographic Magazine and reprinted by special permission.

To

THOSE WHO HAVE STUCK BY ME THROUGH THICK AND THIN: AMONG THE FRONT RANK OF WHOM ARE FLOYD BENNETT, EDSEL FORD AND MY ALWAYS SPLENDID SHIPMATES

FOREWORD

I WISH I were writing this book instead of only its foreword. I would put in much that I know Byrd will leave outmuch of his own life and achievements. After years of association with this young flyer I find he makes light of what most of us would weigh heavily.

Byrds polar and trans-Atlantic flights were but incidents in many years of high adventure. He went around the world alone at the age of twelve. After graduation at Annapolis he helped put down two revolutions in the West Indies. He distinguished himself by years of splendid service with our battleship fleet.

Not the least of all this unwritten record is the fact that he has been officially cited twenty times for bravery or conspicuous conduct. He has received the thanks of Congress as well as the four highest medals the country can give: Congressional Medal of Honor, Congressional Life Saving Medal, Distinguished Service Medal and the Flying Cross. Probably no other man has all of these decorations.

These are but a few of the larger items that Byrd modestly omits from his yarn.

Some of the more specific details that occur to me as regards the great part he has played in promoting aviation are equally important and should be printed between these same covers.

For instance, I attribute to Byrd a very large part in having achieved a Bureau of Aeronautics for our Navy. The formation of this bureau has greatly advanced the development of aviation in the Navy.

Byrd thrilled the world by reaching the North Pole by air and, not content with this success, navigated the North Atlantic by air through two storms when for over twenty hours he saw neither land nor sky nor sea. Yet he arrived over Paris only to find there the centre of another storm area, with the visibility so low he could not see the landing field. To have tried to land would have resulted in the death of others. So he set out for the sea. In spite of storm and darkness he was able to navigate a true course to the lighthouse over a hundred miles away.

It is worthy of especial note that in every case his exploits have been in the name of science. Two of many facts prove this: Last year he could have taken enough extra fuel to keep him in the air over France until morning had he not insisted on eight hundred pounds of scientific equipment and two extra men to make observations and to demonstrate that passengers could be carried. He accepted the hazard of flying in bad weather, realizing the increased opportunity for helpful meteorological research.

Byrds generosity and unselfishness have never received full credit. I happen to know that he gave up a chance to make $100,000 in connection with the newspaper serial rights to his Atlantic flight because the offer did not properly assure financial reward for the three men who accompanied him.

It was not generally known that Byrd very generously coached the navigators of some of the entries in the trans-Atlantic air race, without any thought of the effect on his own chances of being the first to cross the ocean to France.

It is not generally known that Byrd has steadfastly refused to commercialize his expeditions.

I remember years ago when he and I discussed the hazards of such a flight. He said:

The worst possible thing that can happen is for the pilot to reach Paris in darkness and fog and storm.

This combination is exactly what happened on the night of June 30, 1927: a situation that would have been fatal to a leader with less skill and courage, and who had prepared less carefully.

I am glad we have Byrd. It is his idealism, modesty, unflagging industry and devotion to the scientific advance of flying that combine to make him so immeasurably valuable to aviation today.

WILLIAM A. MOFFETT,

Rear Admiral,U. S.Navy,

Chief of Bureau of Aeronautics.

SKYWARD

CHAPTER I

THE FLYERS VIEWPOINT

ONE of my first and most striking impressions of aviation came the day a man rushed into my stateroom aboard the battleship waving a newspaper that had just been brought us by the pilot.

For Gods sake, listen to this 1 he exclaimed. Jack Towers has fallen fifteen hundred feet in an airplane and lived to tell the tale.

I couldnt believe it.

He was thrown out of his seat. (In those days the flyer sat right out in the open on a little bench.) But he caught by a brace and dangled in mid-air. On the way down he kicked at the control wheel. Apparently he righted the plane just before it hit. Think of the nerve of the man!

I did think of his nerve; and many times since Ive admired the courage of those early pilots who flew thousands of feet in the air with defective machines about which they knew almost nothing. And its good to feel that my friend, Commander John W. Towers, U.S.N., the hero of the incident, is alive today and still a flyer of note.

The horror people felt fifteen years ago in reading about Towers escape is still felt when newspapers print tragic details of some aeronautical accident without regard for technical reasons behind the accident. As a result the average citizen still looks on flying as one of the most attractive forms of suicide.

If I had a son twenty years old today and he should come to me with the question: Is it all right for me to fly? Id answer: Go to it. And I hope you get your pilots license soon because I want you to do a lot of flying before youre through.

He might break his neck. But also he might be run over by a taxi, bum up, catch pneumonia or be struck by lightning. Those things happen to people every day.

I would like any young man who likes the idea of flying to go into aviation today first because I believe that, given reasonable perfection of equipment and training that is available today, it is thoroughly safe to make other than pioneer flights. Secondly, I know of no other profession, trade or industry that in the coming fifty years is likely to exert a more profound or far-reaching influence on civilization.