THOMAS H. DAVENPORT & BROOK MANVILLE

Harvard Business Review Press Boston, Massachusetts

Copyright 2012 Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Requests for permission should be directed to , or mailed to Permissions, Harvard Business School Publishing, 60 Harvard Way, Boston, Massachusetts 02163.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Davenport, Thomas H., 1954

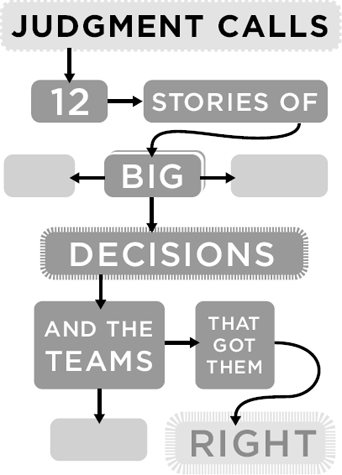

Judgment calls : twelve stories of big decisions and the teams that got them / Thomas H. Davenport, Brook Manville.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-4221-5811-1 (alk. paper)

1. Decision making. 2. Problem solving. I. Manville, Brook, 1950- II. Title.

HD30.23.D3718 2012

658.4'03dc23

2011040344

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Publications and Documents in Libraries and Archives Z39.48-1992.

Foreword

At the outset of a book of stories about judgment, perhaps the way to begin is by telling the story behind the book itself. In the spring of 2010, Tom Davenport and I met for lunch, not with any thought of embarking on a new project but only to catch up. But with two disasters much in the news at the timethe continuing fallout from the global economic meltdown and the explosion of BP's Deepwater Horizon oil platform in the Gulf of Mexicoour conversation kept returning to the question of why it is so hard for organizations to do the right thing.

Our prior research together, spanning two decades, was a source of pride for us. We had focused on knowledge in organizations rather than the more prevalent subjects of information technology and data management and felt we had made a serious difference in at least some management thinking, conversation, and actions. Knowledge, we had argued, was the most valuable asset in modern organizations, and their success depended on their attention to cultivating it, sharing it, and using it.

Now, however, we had to admit that the catastrophes being visited on the world weren't owing to failures of knowledge. Not at all. Who knew more about finance than the employees of the firms that precipitated the financial crisis? Their halls were full of Ivy League graduates rubbing shoulders with the world's leading economists and finance professionals. How could anyone say there wasn't sufficient know-how? And who knew more about how to rein in the risks of their operations than the regulators? Often hired directly from the very entities they were to regulate, they had not only the requisite intellectual tools to understand complex financial structures but intimate familiarity with how they were being applied. Yet all this knowledge, the product of the very strong investments in human capital these organizations made, had brought us to our collective economic knees. So what was missing if it wasn't information or even knowledge? Try judgment.

As that conversation led to others, it wasn't long before Tom and I asked Brook Manville to join the discussion. Not surprisingly, given how long we have been friends and colleagues, he had also been thinking along the same lines. All of us knew something of the existing literature on judgment, which is not unsubstantial. We wondered whether its lessons had simply gone unheeded, or whether it fell short in some way of offering the right lessons for today's organizations.

What we discovered, first, was that the wealth of material already published on judgment treated it as only an individual capacity and exercise. Whether the source is an ancient one, like Aristotle's inquiries into practical wisdom, or a thoroughly modern one, like Dan Ariely's fascinating behavioral economics studies, the focus is on the sole actor and his or her ability to choose a wise course of action. At the same time, most writing on judgment conflates judgment and decision making, to the former's disadvantage. People chipping away at the subject tend to opt for one of two modes, approaching it either as an application of mathematics (following the hugely influential Howard Raiffa) or as a branch of individual psychology (building on Herbert Simon's cognitive science).

We discovered, in other words, that no one was looking into the workings of what we term organizational judgmentthe collective capacity to make good calls and wise moves when the need for them exceeds the scope of any single leader's direct control. We wanted to know why some organizations manage to display good judgment while others seem to lack it. If a group's judgment is something other than the sum total of the practical wisdom of individuals in the group, then we wanted to know what it is, how it is called upon in moments of need, and how to get more of it.

Very briefly, organizational judgment is to group decisions what individual judgment is to individual decisions. It is what guides organizations when information alone cannot. It is the context in which group decisions are madethe atmosphere of collective experience, bias, and belief that sets the boundaries, the limits, the methods of analysis, the very conversations and vocabularies and stories that are the heart and soul of so many decisions.

Think of a recent decision you were party to. Whether it related only to your own life or to the direction of a group, it was not made in a vacuum. I am willing to bet you did not approach it with Cartesian purity, plotting coordinates and noncontextually weighing factors as if you were considering some crystalline structure. No, you made that decision in a social setting. It is that setting which differs from organization to organization, and which is the focus of this book. All the experiences and emotions and histories and individual stories add up to a climate of opinion in any organization that is the soil from which decisions emerge.

All this, Brook, Tom, and I agreed, was uncharted territory and important to explore. We agreed that the way to begin was by going out and talking to real people about the judgment calls their organizations had made. And as we began those visits, we realized that the best way in which we could share what we were learning with others would be to tell those organizations' stories in all their richness.

In terms of my personal involvement, this was a point where the story of the book took a turn. Soon after we began this fieldwork, I became ill for a time and decided I could not responsibly commit to a full share of the research and writing. It was a tough admission, but in the end, the right call. I instead offer this Foreword in gratitudeboth for Tom and Brook's understanding and support, and for the discoveries that populate the pages that follow.

The important news that they bring back from their investigations is that the background and context we call organizational judgment can not only be discerned, it can be managed. Maybe not as much as some might like, but in meaningful ways. Things can be done to ensure that the courses of action taken by organizations are more grounded in reality and a shared sense of what is right. In particular, Tom and Brook found the evidence of what we had suspected: that honing organizational judgment means creating processes and mechanisms that allow discussion and debate and conversation to work its own collective chemistry.

I'm proud to say, then, that I was present at the beginning of something big. Across the history of theorizing about how decisions are best made, we have already seen three eras. First, there was the great man school of thought (a folly that Tom nicely summarizes in .) According to its teachings, judgment was surely accorded central importance, but the judgment was assumed to be an individual characteristicindeed, one of the distinguishing characteristics that separated truly great men (yes, alas, always thought to be men) from the rest of mankind.

Next page