THE ART OF

PROBLEM SOLVING

ACCOMPANIED BY ACKOFF'S FABLES

RUSSELL L. ACKOFF

Illustrations by KAREN B. ACKOFF

JOHN WILEY & SONS

New York Chichester Brisbane Toronto Singapore

Copyright 1978 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada.

Reproduction or translation of any part of this work beyond that permitted by Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act without the permission of the copyright owner is unlawful. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data:

Ackoff, Russell Lincoln, 1919-The art of problem solving.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Problemsolving. I. Title.

HD30.29.A25 658.4'03 78-5627

ISBN 0-471-04289-7

ISBN 0-471-85808-0 (paper)

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22

To

Daniel H.Silberberg

with

gratitude

and

affection

Between truth and lie are images and ideas

we imagine and think are real,

that paralyze our imagination and our thinking

in our efforts to conserve them.

We must continually learn to unlearn

much that we have learned, and learn to learn

that we have not been taught.

Only thus do we and our subject grow.

R. D. Laing, The Politics

of the Family and Other Essays

Vintage Books, New York, 1972

Preface

Over the years, I have been presented to audiences as an architect, philosopher, statistician, city planner, or operations researcher, or as a behavioral, communication, information, management, organizational,and systems scientist. But none of these tells me what I really am as well as did a characterization given to me by a student. He said I was a problem solver.

Problem solving is what I have been trying to do all my adult life, using whatever type of knowledge appeared accessible and relevant to me. In my "early period" I came to problem solving primarily from a philosophical point of view. In my "middle period" I came at it scientifically, keeping philosophy at my side. And now, in my "late period" I find myself preoccupied with the art of problem solving, keeping both philosophy and science ever at my side.

The more philosophy and science I tried to bring to bear on problem solving, the more I came to realize that even together they can assure us no more than adequate solutions to problems. They cannot provide exciting solutions, ones that we call "beautiful." Only the kind of problem solving that involves art can do this. And art implies creativity.

This is a book about creative problem solving. It is addressed to those who either make their living at, or derive their fun from solving problems-or both.

For me, the term "problem" does not refer to the kind of prefabricated exercises or puzzles with which educators continually confront students. It means real problems, the effective handling of which can make a significant difference to those who have them, even if they are philosophers and scientists.

This is neither a textbook, nor a handbook, nor a learned treatise. It it what is left from sifting through thirty years of experience, my own and others, in search of clues on how to make problem solving more creative and more fun. Solving even the most, serious problems can be fun to the extent that we act creatively, and having fun in a creative way is also very likely to increase the quality of the solution it yields.

It will be apparent to even the casual reader that I had a lot of fun writing this book, much of it derived from the fact that my daughter Karen did its illustrations. Having her do them turned out to be the only way I have found to get her to read anything I have written.

I was assisted greatly in preparing the final version of this book by suggestions made by Paul A. Strassmann. Whenever I doubted whether writing this sort of thing was my "ball of wax," my good friend Stafford Beer encouraged me to keep at it. I hope he will not be sorry.

RUSSELL L. ACKOFF

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

January 1978

THE ART OF PROBLEM SOLVING

PART onethe art

CHAPTER ONE

Creativity and Constraints

Most managers and management educators have a list of what they consider the essential properties of good management. I am no exception. My list, however, is unique because all the characteristics, properly enough, begin with C:

Competence

Communicativeness

Concern

Courage

Creativity

The greatest of these is creativity.

Without creativity a manager may do a good job, but he cannot do an outstanding one. At best he can preside over the progressive evolution of the organization he manages; he cannot lead it to a quantum jump-a radical leap forward. Such leaps are required if an organization is to "pull away from the pack" and "stay out in front." Those who lack creativity must either settle for doing well enough or wait for the breaks and hope they will be astute enough to recognize and take advantage of them. The creative manager makes his own breaks.

Educators generally attempt only to develop competence, communicativeness, and (sometimes) concern for others in their students. Most of them never try to develop courage or creativity. Their rationalization is that these are innate characteristics and hence can be neither taught nor learned.

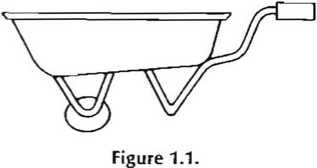

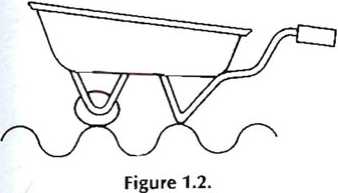

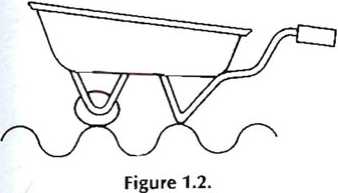

That creativity can be acquired seems to follow from the fact that it tends to get lost in the process of growing up. Adults recognize that young children, particularly preschoolers, are full of it. I recall a dramatic illustration of this point given by an eminent student of creativity, Edward de Bono, in a lecture to an audience consisting of managers and management scientists. He drew a picture on the blackboard of a wheelbarrow with an elliptical wheel (Figure 1.1) and asked the audience why it had been designed that way. There was a good deal of squirming, murmuring, and embarrassed tittering, but no answer. De Bono waited, letting the discomfort grow. He then told his audience that he had recently asked the same question of a group of children and almost immediately one of them had rushed to the board and drawn a squiggly line such as that shown in Figure 1.2. "The wheelbarrow is for a bumpy road," the child had said. The audience blushed and laughed self-consciously.

Most of us take for granted both the creativity of children and its subsequent loss. We do not try to understand, let alone prevent, this loss. Yet the disappearance of creativity is not a mystery; the explanation lies in a query that Jules Henry (1963), an American anthropologist, once made: What would happen, he asked,

... if all through school the young were provoked to question the Ten Commandments, the sanctity of revealed religion, the foundations of patriotism, the profit motive, the two party system, monogomy, the laws of incest, and so on .... (p. 288)

The answer to Henry's question is clear: society, its institutions, and the organizations operating within it would be radically transformed by the inquisitive generation thus produced. Herein lies the rub: most of the affluent do not want to transform society or its parts. They would rather sacrifice what future social progress creative minds might bring about than run the risk of losing the products of previous progress that less creative minds are managing to preserve. The principal beneficiaries of contemporary society do not want to risk the loss of the benefits they now enjoy. Therefore, they, and the educational institutions they control, suppress creativity before children acquire the competence that, together with creativity, would enable them to bring about radical social transformations. Most adults fear that the current form and functioning of our society, its institutions, and the organizations within it could not survive the simultaneous onslaught of youthful creativity and competence. Student behavior in the 1960s convinced them of this.