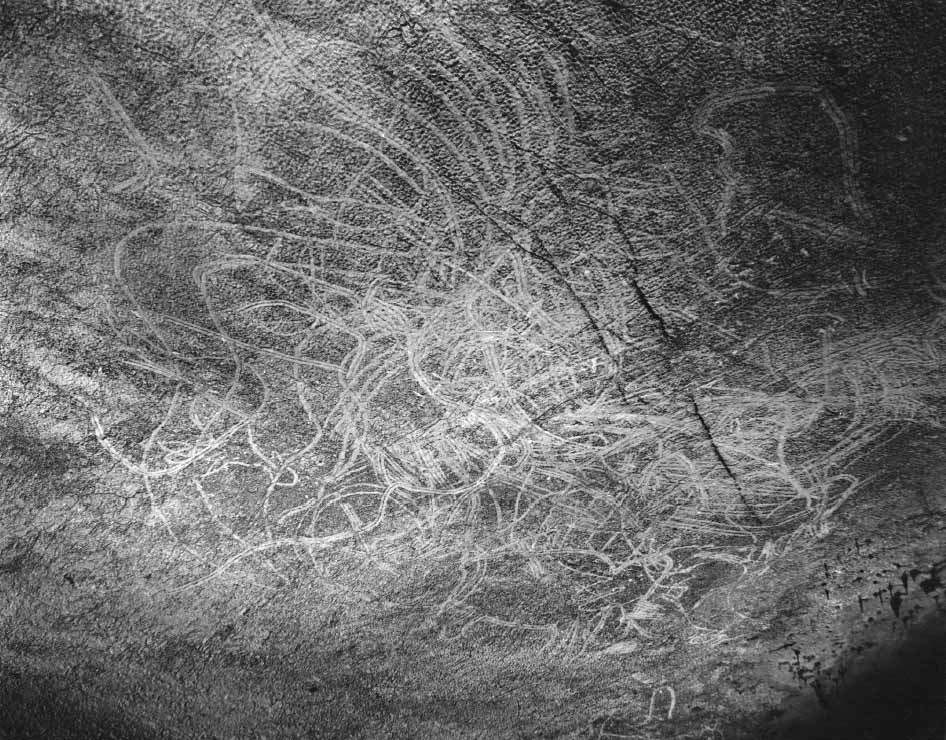

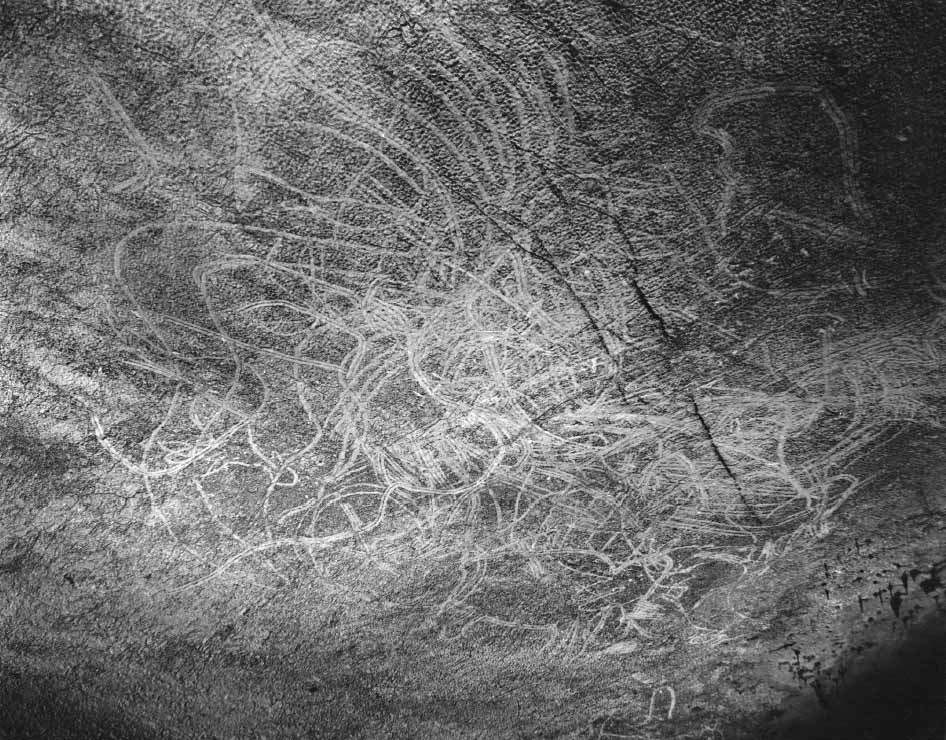

Frontispiece:

. Finger-flutings in the soft rock surface at Pech-Merle (Lot).

About the Authors

Michel Lorblanchet is a leading French specialist in the field of Palaeolithic art. In his former roles as Director of Research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and research consultant for the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies he pioneered experimental methods of reproducing ancient art, as well as scientific methods for its dating. His Art parital:Grottes ornes du Quercy (Editions du Rouergue, 2010), the sum of forty-five years of research, is considered the definitive work on the art of the Quercy region, which includes more than thirty painted caves.

Paul Bahn is co-author of Thames & Hudsons hugely influential and bestselling textbook Archaeology: Theories, Methods and Practice, and has also published a variety of popular books, including Easter Island: Earth Island (with John Flenley), Mammoths: Giants of the IceAge (with Adrian Lister) and Images of the Ice Age, widely regarded as the standard introduction to cave art.

Pierre Soulages is a painter, engraver and sculptor, described by French President Franois Hollande as the worlds greatest living artist. He is known as the painter of black, and cites prehistoric art as the inspiration for his fascination with the colour and non-colour: for thousands of years, men went underground, in the absolute black of grottoes, to paint with black. His work is displayed in museums worldwide, including the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Tate Gallery, London. In 2014 the Muse Soulages, celebrating his long lifetimes work, was opened in his hometown, Rodez, France.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

A History of Pictures: From the Cave to the Computer Screen

The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art

A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney

Cave Art

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For Jean-Marie and Hlne Le Tensorer, and for Colin and Jane Renfrew

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 as

The First Artists: In Search of the Worlds Oldest Art

ISBN 978-0-500-05187-0

by Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

and in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

The First Artists: In Search of the World's Oldest Art

2017 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

This electronic version first published in 2017 by

Thames & Hudson Ltd, 181A High Holborn, London WC1V 7QX

This electronic version first published in 2017 in the United States of America by

Thames & Hudson Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 978-0-500-77391-8

ISBN for USA only 978-0-500-77392-5

To find out about all our publications, please visit

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

On the :

Red stag in the cave of Pech-Merle, France. Recording by Michel Lorblanchet.

Contents

Theories, chimps and children:

early attempts to tackle the problem

Finding art in nature:

the first stirrings of an aesthetic sense

Can we see art in the first tools?

Polyhedrons, spheroids and handaxes

All work and no play?

Looking at marks on bones and stones

Figuring it out:

pierres-figures and the first carvings

Jingles and bangles:

the origin of music and decorated bodies

The first art in the landscape:

dots and lines

The writings on the wall:

the earliest cave art

A global phenomenon:

the appearance of rock art around the world

Foreword

When you go to the Louvre, you see five centuries of paintings, but even if you saw ten, what are ten centuries when compared to three hundred? Because you are seeing at least two or three hundred centuries in the prehistoric painted caves, including the ones discovered recently, like Cosquer or Chauvet.

So should we look for meanings? One is perfectly entitled to do so, and we may even find them one day but well never be able to verify them! On the other hand, where the ancient artists techniques are concerned, if you put forward a hypothesis, you can verify it. This is what Michel Lorblanchet does, and thats why I was immediately interested in his work.

When I enter a painted cave, like everyone, I am overwhelmed; one is entering a belly, the belly of the earth! And when, in a moment of intense emotion, I discover the products of people from hundreds of centuries ago, I am more profoundly moved than when I go to the Louvre. There are certainly things in the Louvre that overwhelm me, but they are far more recent they are only a few centuries old! I feel much closer to the lions of Chauvet than to the Mona Lisa. When I see their works, I consider the prehistoric artists to be my brothers.

What interests me about these ancient paintings is what happened with the people who made them, in terms of materials that is the best way to approach these things, far better than trying to figure out their meaning because its well known that when you talk of meaning, youre only talking about yourself. We dont have the same myths, or the same society, as the authors of the prehistoric paintings. Our view of them is personal. So what is a work of art? What interests me are not the reasons why the paintings were made, but the practices of the painters. What causes me to wonder and perplexes me is the way they painted.

Painting began with black Black is an original material! Painting began with black, red, earth and in the shadows, in the darkest places, beneath the earth, where one can imagine that people could have sought different colours perhaps they already knew that black is the colour that includes all colours it is the colour of light! The word presence is the key word for everything that is artistic: a work is eternally present.

Pierre Soulages

In this book, we shall strive to avoid imposing any personal point of view onto the products of prehistoric societies, or promoting any kind of theory about art: in any case, what is art? In the words of Ernst Gombrich (1950: 4), There really is no such thing as art: there are only artists!

Definitions of the word art generally incorporate notions of beauty and pleasure, but such notions tend to trouble archaeologists, who reject the term prehistoric art because art, as we might propose to define it today (an accomplishment of human skill, the aim of which is the satisfaction of an aesthetic pleasure, not the meeting of any utilitarian need), was supposedly unknown to early human populations. This problem has sparked an international debate attempting to replace the term rock art with something more accurate and suitable (although nobody has succeeded so far!). Many scholars are concerned that the term art has led to monolithic, all-encompassing theories of artistic behaviour, squeezing 40 millennia of hugely varied image-creation into a single category. And what we today call contemporary art, with its notions of the death of art or end of art, can shed little light on the world of prehistoric creations. One certainly needs to be wary of modern aesthetic discourse, to see in figures on rocks and cave walls something more than their simple beauty and their formal qualities. The study of early art must strive to recreate how the people of the past perceived and used the images.