CONTENTS

FOR PETER & GLYNIS BAHN, AND FOR HENRY CLEERE

For their help in putting together this pot-pourri (in every sense!), we would like to extend our warmest thanks to the following friends and colleagues Dave Evans, Bryan Sitch, Pete Sweeney, David Gill, Simon James, Steven Snape, Chris Edens, Carol Andrews, Karen Wise, Frank & A. J. Bock, Georgia Lee, Angelo Fossati, Gina Barnes, Bert Woodhouse, Kathy Cleghorn and Jan Wisseman-Christie.

I was 12 years old when Archaeology first gripped and terrified me. It was the moment when the high priest of Amun, George Zukor in his fez and blazer, incanted the spell which enabled 3000-year-old Boris Karloff to push the lid off his sarcophagus and stagger away to throttle anyone wearing an archaeologists uniform. From then on, any book featuring mummies was on my syllabus.

I didnt end up as an Egyptologist because everything on Sherlock Holmes, Wilson the Wonder Runner and War was also required reading, but I fancied myself as having a fair knowledge of Pharaohs. What a tremendous let down however when, decades later, my daughter, Sylvia, after taking tourists around the treasures of Egypt, told me about some of the more unusual practices in which the Kings indulged!

How was it that I didnt know that Seti masturbated for purposes other than fun? Gradually it seeped through to me that this fact and many others had been suppressed because, in the estimation of the great archaeologists, decent folk were not ready, and never would be, for such indecent revelations.

It was the old hypocrisy of censorship by prudery: fine for the wall-painting to show a Warrior King collecting mountains of foreskins from the fallen enemy, but absolutely forbidden to allow him to be seen exercising his own! I then began to speculate on what else had been locked away about prehistoric man, Egypt, the Maya, the Greeks, Romans and Chinese, etc; so I did a little probing, but the secrets were so well kept that only a professional would know where to dig. I called Paul Bahn, and this book was born.

Bill Tidy

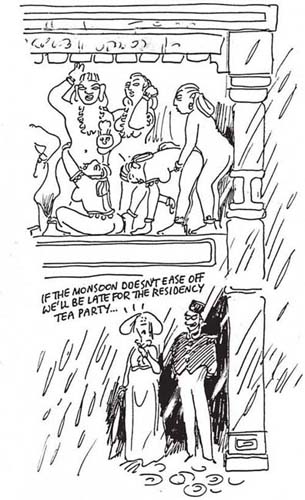

At Khajuraho, India, the explicitly erotic subjects are presented with a liveliness and delicacy that deeply shocked the English colonial archaeologists who excavated the site in the early twentieth century. Guidebooks at that time discouraged visitors to the site for fear of impropriety and moral corruption,

Archaeology is a bizarre pastime it aims to reconstruct the past, to bring it back to life, by studying the objects and traces that have managed to survive years, centuries or millennia of decay or disturbance. Yet in the nineteenth century and the early part of our own, the picture of the past was carefully sanitised. There were endless learned books and papers devoted to the classification of objects, to the deeds and monuments of rulers, and to burials and treasures, but there was scant mention of a mass of equally fascinating aspects of ancient life, which would have served to flesh out the picture, made it more vivid and struck a chord with ordinary folk the humorous, the scatological, and the sexual. Most of the silliness and bawdiness that helps make life worthwhile and which is such a vital part of being human was deliberately concealed or destroyed. Why?

In large measure this was due to prudishness and snobbery. It must have seemed beneath the dignity of learned scholars in the booklined groves of Academe to deal with such trivia most of them were writing for their peers, after all, not for the great unwashed, and prudery was very much the norm through Victorian times and beyond. It resulted not only in cosmetic solutions such as the fig leaves placed over naughty bits of Classical statues, but also, at times, in outright obstruction. For example, cultured persons are known to have destroyed many specimens of prehistoric Moche pottery from Peru depicting bestiality (primarily involving men and llamas) which we know from sixteenth-century chroniclers was a widespread habit in highland Peru out of misguided patriotism, in an effort to erase evidence of an abominable practice, and not wishing people to get the wrong idea about their ancestors!

Other items are still being kept hidden for example, the Turin Papyrus, a rare piece of sexually explicit imagery from ancient Egypt, is the most famous object in Turins magnificent Museum of Egyptology, yet it is not on display allegedly to prevent bambini from seeing it nor is any copy of it available at the museum in book, slide or postcard!

In general today the pendulum has swung the other way, and as archaeology becomes ever more popular the public is increasingly being given a picture of the past with warts and all. Children, especially, love the scatological aspects of the past such as multi-seated Roman toilets, or preserved turds and it is no accident that the man using the cesspit is the most popular bit of the Jorvik Viking Centre in York, as witnessed by the sale of its scratch and sniff postcard .

In putting this book together, therefore, we have unashamedly sought to put the spotlight on the more scurrilous or even shocking aspects of the past, the kind of material which would had Victorians reaching for the smelling salts or which would, until fairly recently, been published in passages of Latin or Greek to avoid shocking the uneducated!

Our brief was that we could be as obscene or politically incorrect as we wished, provided that everything we included was true. Well, we cannot guarantee that it is all true, but we can assure readers that we have not made up anything at all you could not make up things like this! Absolutely everything in this book has been published or recorded somewhere. Our title may lead some readers to imagine that we have drawn only on what many consider to be the main focus of archaeology, that is, the artifacts and ruins that have come down to us from the past. We have certainly done this where possible but, had we limited ourselves to such sources, the book would have been far slimmer and much more speculative as we tried to guess the uses of particular objects or rooms. But since, in fact, archaeology simply means the study of ancient things, or of the material traces of the human past, it follows that the invaluable writings that have survived from our ancestors, and especially those from the Classical world, can justifiably be included here and we have drawn on them heavily for the unique insights they provide into aspects of their societies which otherwise would be lost for ever, or which would forever remain tantalisingly ambiguous in artistic depictions.

Archaeology is a vast, multi-faceted subject, with many roles to play, but one of its major functions, as the late Glyn Daniel often emphasised, is that of providing pleasure, whether through the simple joy of learning and discovery, the contemplation of beautiful images or objects, or the sheer fun of finding out that our ancestors were not always serious, downtrodden, spiritual and fearful creatures. They had a sense of humour, they were human beings like ourselves, and it diminishes their humanity to hide the kind of material presented here. Although it is all perfectly genuine, little of it has ever found its way into popular books before. Its time to pull off the fig leaves and take a long hard look at the real past.

Some may find this lowbrow little tome offensive. In reply, one can do no better than quote Captain John G. Bourke, the nineteenth-century American scholar whose amazing work of compilation was an invaluable source in preparing our book: As a physician, to be skilful, must study his patients both in sickness and in health, so the anthropologist must study man, not alone wherein he reflects the grandeur of his Maker, but likewise in his grosser and more animal propensities. Or, to put it another way, one may cite a brief text that appeared in several early seventeenth-century books in Tuscany: Reader, if you find something that offends you in this most modest little book, dont be surprised. Because Divine, not human, is that which hath no blemish.