BILL MANLEY is an Egyptologist, university lecturer, museum curator and best-selling author. He teaches Egyptology and Coptic at the University of Glasgow, and is Co-Director of Egiptologa Complutense, Honorary President of Egyptology Scotland and an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Liverpool. He was formerly Senior Curator for Ancient Egypt at National Museums Scotland, and continues to work with archaeological projects in Egypt. His specialist output includes books, catalogues, articles and exhibitions covering such diverse subjects as ancient texts, the history of Egyptology, gold jewelry, the archaeology of Palestine and the worlds earliest philosophy.

Thames & Hudson world of art

This famous series provides the widest available range of illustrated books on art in all its aspects.

To find out about all our publications, including other titles in the World of Art series, please visit www.thamesandhudson.com .

There you can subscribe to our e-newsletter, browse or download our current catalogue, and buy any titles that are in print.

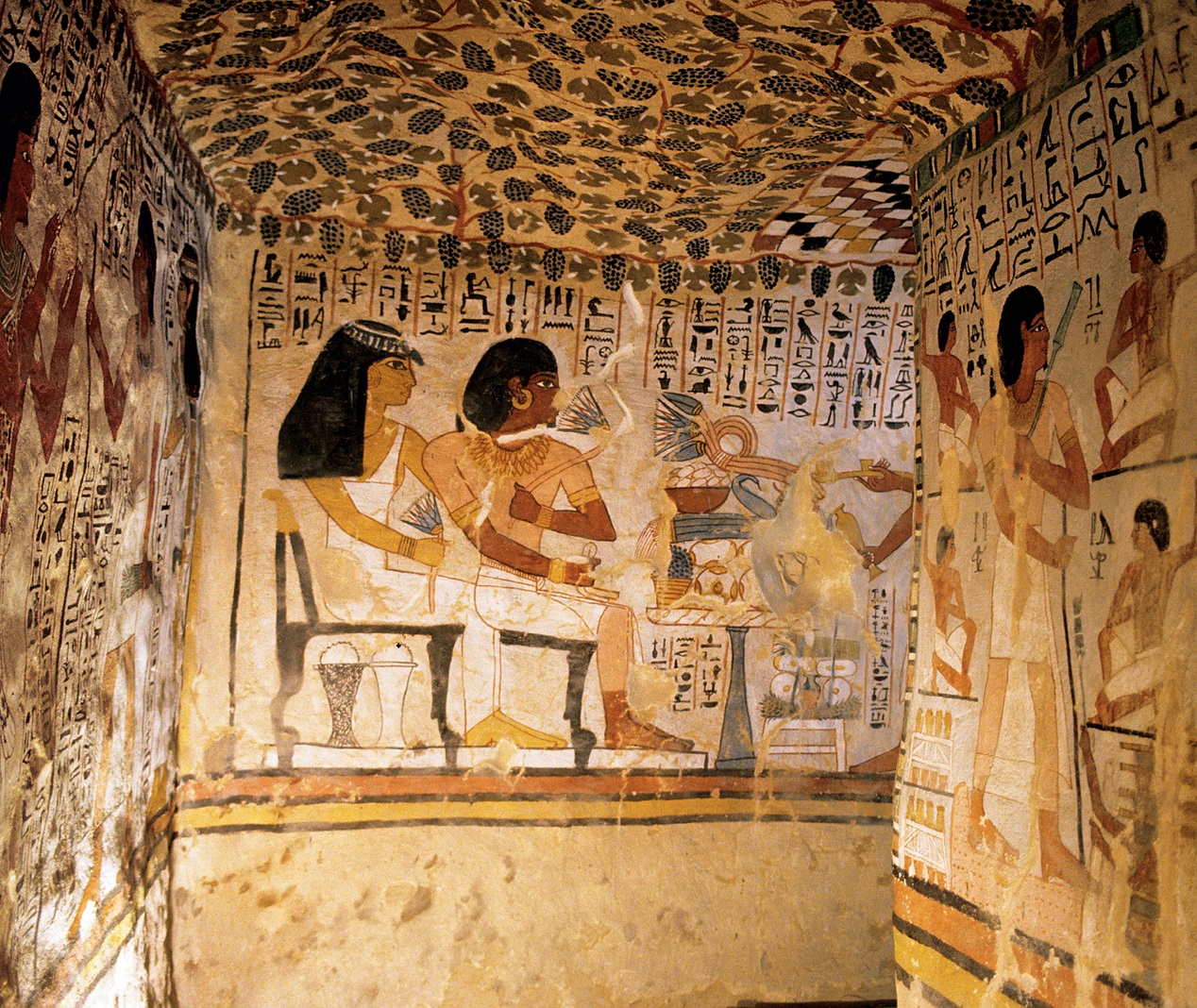

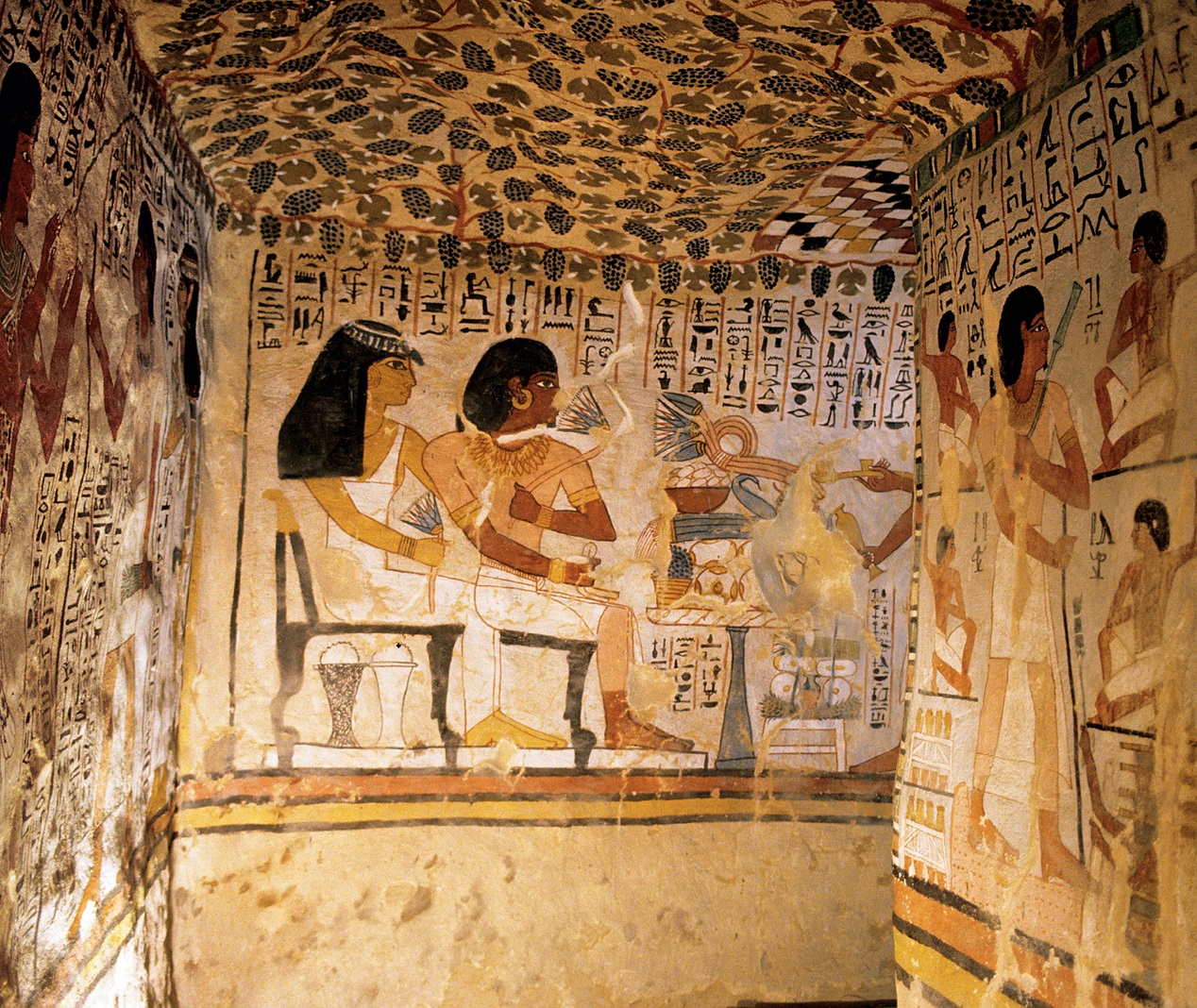

View of the burial chamber of the mayor of Thebes Sennefer (see ).

Now, there is a law written in the darkest of the Books Of Life, and it is this:

If you look at a thing nine hundred and ninety-nine times, you are perfectly safe;

if you look at it the thousandth time,

you are in frightful danger of seeing it for the first time.

G. K. Chesterton, The Napoleon Of Notting Hill (1904) I.1

To JEB, for the gift of new eyes

Contents

Personifications of the Nile Valley (left) and a temple estate presenting their produce as offerings at the Red Chapel of the female king Hatshepsut (see ).

This book is about the visual art produced in Egypt when the land was ruled by the god-kings, whom we have come to call the pharaohs (albeit the word originally meant the palace). Consequently, it covers thousands of years from the first pharaohs, roughly about 3000 BC, until pharaonic authority dissolved in the national conversion to Christianity, between AD 300 and 350. Visual art, of course, may mean any crafted or decorated objects or surfaces we could sensibly understand as art, which in regard to ancient Egypt includes monumental painting, reliefs and sculpture, as well as smaller items of jewelry, furniture, decorated tiles, dishes and the like. Such artworks were fashioned in wood, ceramics, faience (glazed composite) or glass, and metals, including bronze and gold. Most of all, however, ancient Egyptians worked using stone of many kinds and qualities.

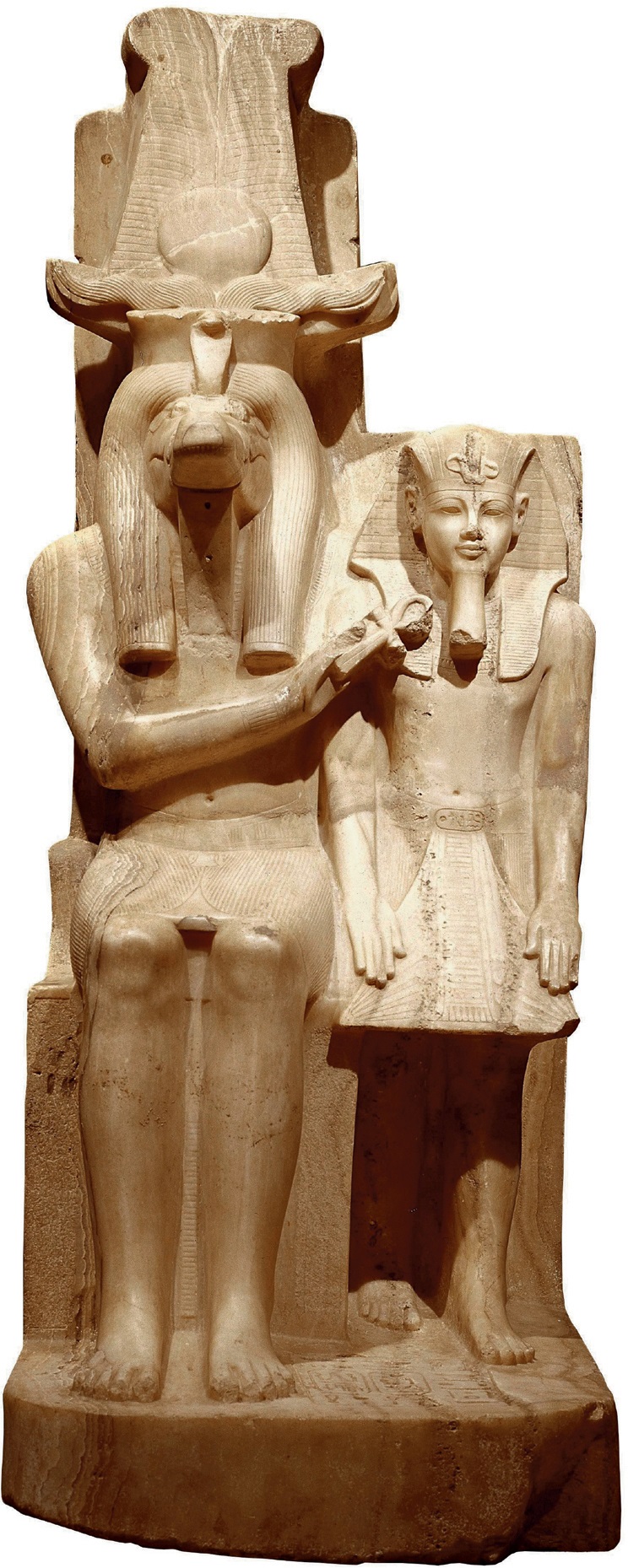

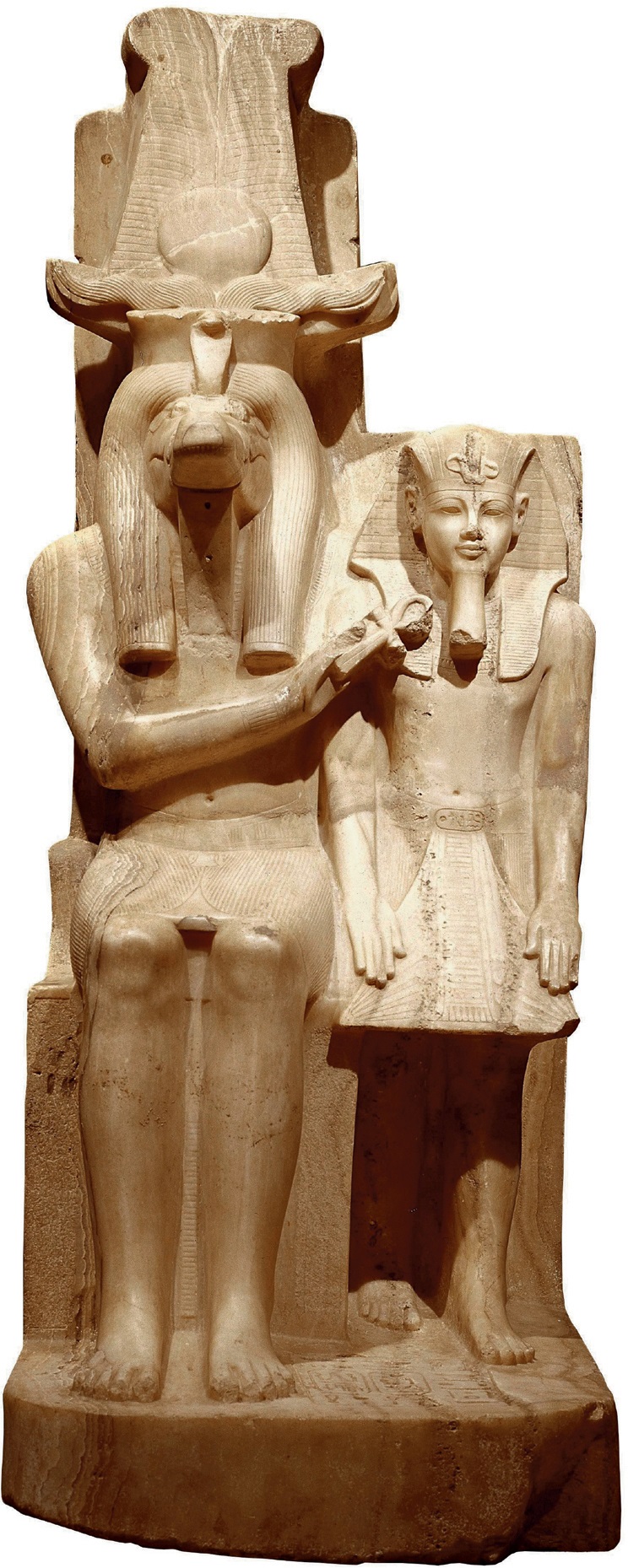

Calcite statue of king Amenhotep III and the god Sobk-Ra. Found near Gebelein. 2.57 m (8 ft 5 in.) high. 18th Dynasty.

The subject may seem too vast and disparate for a single book, and in points of detail it certainly is. However, even a quick survey of ancient Egyptian artworks reveals how the majority come from a handful of contexts, principally tombs and temples. These are contexts we may characterize as sacred places, where humans attended gods, the living considered the dead, and where minds contemplated the eternal. Of course, there is art from other places that must also be considered, especially art from domestic contexts. However, we have surprisingly little, as we shall see in . Moreover, some contexts where we would expect to find art are mostly not relevant to ancient Egypt, including art from public spaces or official buildings. Even the wealth of jewelry surviving from pharaonic times on closer inspection turns out to have come down to us in burials. So we may begin by suggesting that ancient Egyptian art at least as it survives today is a subject brimful of antiquity but more modest in scope.

Initial observations

The finest art of ancient Egypt may fairly be described even in our modern, sophisticated age using words such as beauty, elegance and grace. To take an example, in 1967 a human-sized, calcite statue of the god Sobk-Ra was discovered by accident among the ]. The statue shows the massive, crocodile-headed god embracing the relatively diminutive, yet solid and elegant, figure of the once mighty pharaoh, Amenhotep III (c. 1390c. 1353 BC). Despite the gods reptilian face, there is neither horror nor disgust in the composition, but serenity. The god has a human body, and is able to embrace the king like a proud father posing for a photograph. Although there is no sparing the outlandish details of his face, each individual tooth finely scored in the stone helps form the half-smile of the Mona Lisa. The king smiles likewise, and his arms have settled upon his kilt in a gesture of greeting (to us?). He is evidently not intimidated by his companion, and, we may note, his face is as handsome as the others is monstrous. Individual barbs in the gods high-plumed crown, the folds of the kings iconic headcloth (or nemes) and the ever-present coiled uraeus-cobra on his brow, even the lines of his make-up, have been worked distinctly into the soft-stone surface. The gods solid knees and legs are shapely and muscular, and give the impression he may stand up at any moment, so fluid and precise is the modelling. The waxy stone has been carved into forms so plastic as to seem lifelike, and almost flawless after three and a half millennia.

What does a statue so beautifully carved tell us? Undoubtedly the relationship between the two characters god and pharaoh is crucial, intimate, and presented in human terms (family, serenity, touching, welcome). We see the crowned king, but beside him the god more massive and enthroned holds still greater authority. Both of them look towards the viewer, revealing no specific attitude nor emotion, though the confrontation is not hostile. As we look at the king, whose height the sculptor has arranged to meet our eye-line, the gods gaze remains slightly above the engagement. What does this engagement have to do with the function of the statue? Who was its intended audience?

Looking more closely, we see how the gods far hand is pressing the ancient hieroglyph  reading life onto his companion in fact raising it to his face. His crown carries the same coiled uraeus-cobra as the kings, so whatever the uraeus represents (domination, actually) applies to both of them. His throne takes a simple form, barely more than a cube with a step for the base and a back pillar rising to support the massive plumed crown, and it is covered at the sides with hieroglyphs that elaborate on the subject of the statue. In fact, where the statue is now on display, in the Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, it is possible to walk round and see that the back too is formally plain but entirely covered with columns of clearly cut hieroglyphs. Through them, Sobk-Ra is made to speak to the king (not us) and state that he is, indeed, Amenhoteps father and he does, indeed, love him. Specifically, he has made his sons perfection, given him the festivals of kingship a million times over, and established him in the world according to the pattern of the Sun in the sky, so he may rise in splendour each day and endure until the end of time.

reading life onto his companion in fact raising it to his face. His crown carries the same coiled uraeus-cobra as the kings, so whatever the uraeus represents (domination, actually) applies to both of them. His throne takes a simple form, barely more than a cube with a step for the base and a back pillar rising to support the massive plumed crown, and it is covered at the sides with hieroglyphs that elaborate on the subject of the statue. In fact, where the statue is now on display, in the Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, it is possible to walk round and see that the back too is formally plain but entirely covered with columns of clearly cut hieroglyphs. Through them, Sobk-Ra is made to speak to the king (not us) and state that he is, indeed, Amenhoteps father and he does, indeed, love him. Specifically, he has made his sons perfection, given him the festivals of kingship a million times over, and established him in the world according to the pattern of the Sun in the sky, so he may rise in splendour each day and endure until the end of time.

Next page

reading life onto his companion in fact raising it to his face. His crown carries the same coiled uraeus-cobra as the kings, so whatever the uraeus represents (domination, actually) applies to both of them. His throne takes a simple form, barely more than a cube with a step for the base and a back pillar rising to support the massive plumed crown, and it is covered at the sides with hieroglyphs that elaborate on the subject of the statue. In fact, where the statue is now on display, in the Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, it is possible to walk round and see that the back too is formally plain but entirely covered with columns of clearly cut hieroglyphs. Through them, Sobk-Ra is made to speak to the king (not us) and state that he is, indeed, Amenhoteps father and he does, indeed, love him. Specifically, he has made his sons perfection, given him the festivals of kingship a million times over, and established him in the world according to the pattern of the Sun in the sky, so he may rise in splendour each day and endure until the end of time.

reading life onto his companion in fact raising it to his face. His crown carries the same coiled uraeus-cobra as the kings, so whatever the uraeus represents (domination, actually) applies to both of them. His throne takes a simple form, barely more than a cube with a step for the base and a back pillar rising to support the massive plumed crown, and it is covered at the sides with hieroglyphs that elaborate on the subject of the statue. In fact, where the statue is now on display, in the Luxor Museum of Ancient Egyptian Art, it is possible to walk round and see that the back too is formally plain but entirely covered with columns of clearly cut hieroglyphs. Through them, Sobk-Ra is made to speak to the king (not us) and state that he is, indeed, Amenhoteps father and he does, indeed, love him. Specifically, he has made his sons perfection, given him the festivals of kingship a million times over, and established him in the world according to the pattern of the Sun in the sky, so he may rise in splendour each day and endure until the end of time.