Writing is never a one-person endeavour and I am eternally grateful for those wonderful people who believed, encouraged, and supported me throughout this adventure.

Foreword

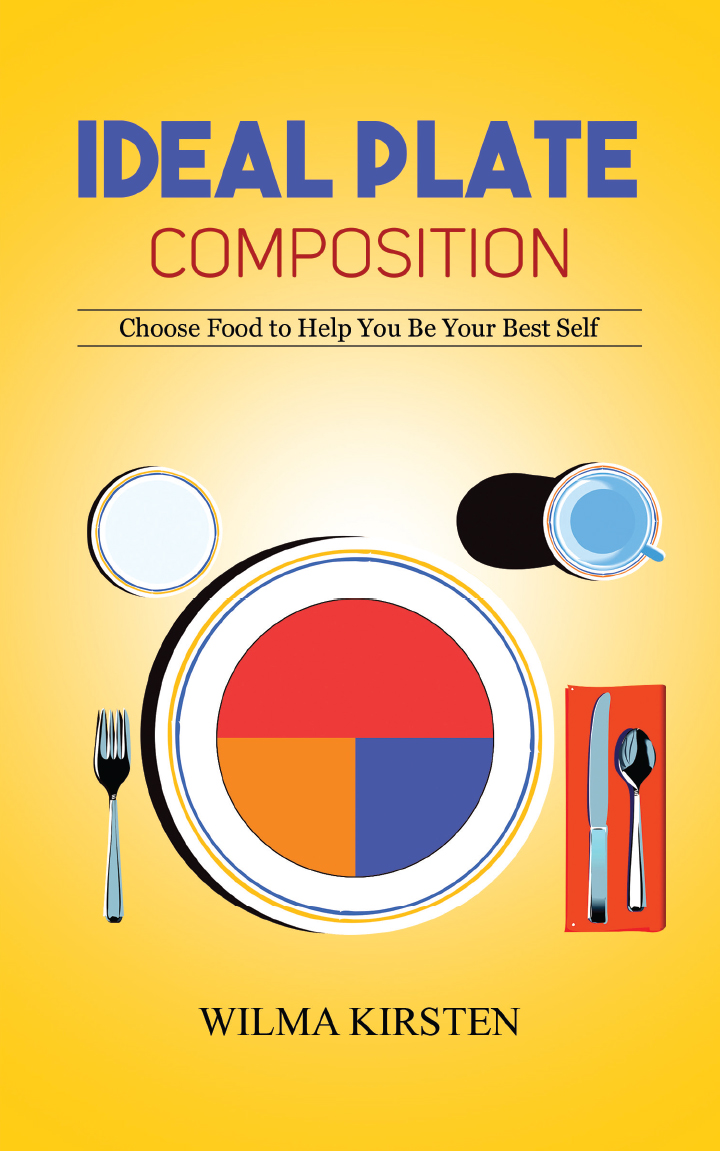

The book you are holding may turn out to be one of the most important books you have read. Books related to health and healthy eating are abound and there are many good books one could read. But too many are either too academic or make unfounded claims based on wishful thinking. This book strikes an excellent balance, distilling scientific research and clinical experience spanning many years into a very approachable format. The core message of this book is easy to understand and together with the supporting knowledge you will learn, it will allow you to incorporate and maintain changes in your diet that will have long-lasting effects. These changes, as you will see in the vignettes presenting a person in each chapter, can make a huge difference to your health and mental state.

There are many things that contribute to our wellbeing, and these can be seen to fall broadly into the three categories of physiological, psychological, and social. Food and eating occupy all three categories and, whilst nothing is a panacea, Wilma proposes the one thing that can affect all three and is likely to benefit everyone, regardless of what ails them.

There are things that are necessary for survival and things that contribute to our well-being. Sufficient oxygen, temperatures within a fairly narrow range, water, and food are all required to survive. Lack of oxygen or extreme temperatures will result in a quick demise, lack of water will take a few days, and lack of food is likely to result in an untimely death in weeks. On the other hand, a safe environment, friendship, intimate relationships, validation, and good nutrition are all things that contribute to our well-being, even if a lack of them would not necessarily be life-threatening.

As you may have noticed, food falls into both categories. It is essential for us to eat or we will starve, but it is also important that we eat food that will nourish us if we want to be well. Even if we ignore the social and psychological aspect of food and eating, we can see that it occupies a unique place in our quest for health.

Necessary requirements are, if met, mostly ignored by us. Unless we often suffer from lack of oxygen, are exposed regularly to extreme temperatures or states of severe dehydration, the psychology is fairly simple and can be described in terms of homoeostasis, the way an organism strives to maintain a state of balance. If temperatures drop, we employ physiological and behavioural strategies to maintain our core temperature. Arrector pili contract to warm us up, we move out of the elements, wear warmer clothes, start a fire, and possibly even decrease blood flow to the extremities to maintain our core temperature. The key point here is that, from a psychological point of view, unless we are physically threatened, the maintenance of homoeostasis is almost totally unnoticed.

As nutrients are very important for many physiological functions, it is sensible to wonder whether our appetites are driven by homoeostasis too. You may have come across the belief that, if you feel like something, it is possibly because your body is telling you to replenish some nutrient or other. It is appealing to think that we crave that chocolate because it contains magnesium and we are probably deficient. Much of the early research into the psychology of eating followed this thought process, starting with a basic homeostasis of glucose or lipids and progressively getting more sophisticated. The fundamental problem with assuming that we seek foods that replenish the nutrients that we need is the sheer number of nutrients required for optimal health and the variation in nutrient content in the foods we eat. This approach is still proposed by some people because it makes sense and they may even present supporting evidence in research. Some research seemed to support the homeostatic principle as a driver for what we eat where, for example, rats fed on a diet lacking an essential amino acid got sick and later showed a preference for a food containing the nutrient. The homeostatic interpretation was that the rats were seeking food containing what they were deficient in and there was this internal wisdom guiding them to the correct nutrition. This interpretation was refuted by further, similar experiments where either presenting a new, deficient food, or two new foods (one deficient and one not) clearly showed that the rats avoided the food that had made them sick, but they had no preference for the food containing the nutrient they were lacking. The rats had merely learnt that the one food was not making them feel well and thus avoided it. The key point here is that, whilst appealing, the idea that you feel like a certain type of food because there is some ingredient in it that your body needs is not supported by any research. If you feel like something you might benefit from the enjoyment it brings but do not try to justify it as somehow nutritionally beneficial.

Food avoidance is very common and at times we develop very strong dislikes for foods. The strongest of these aversions are those related to foods that were consumed shortly before experiencing nausea or strong gastrointestinal discomfort. One such incident suffices for us to avoid a particular food for the rest of our lives. Most people have a food that they have a strong aversion to because of a single experience and most readers will be able to think of the food and the experience without too much difficulty. This strong aversion makes sense as we would associate these foods with toxicity and thus avoidance of these would be a strong adaptive trait in our evolution. A quick diversion into the concept of psychological conditioning will help us better understand the drivers and mental processes behind this strong aversion.