Perspective

By William F. Powell

www.walterfoster.com

1989, 2013 Walter Foster Publishing, a Division of the Quayside Publishing Group.

All rights reserved.

Walter Foster is a registered trademark.

Artwork and photographs 1989 William F. Powell, except photographs on Shutterstock.

Publisher: Rebecca J. Razo

Art Director: Shelley Baugh

Senior Editor: Stephanie Meissner

Associate Editor: Jennifer Gaudet

Assistant Editor: Janessa Osle

Production Designers: Debbie Aiken, Amanda Tannen

Production Manager: Nicole Szawlowski

Production Coordinator: Lawrence Marquez

Production Assistant: Jessi Mitchelar

This book has been produced to aid the aspiring artist. Reproduction of work for study or finished art is permissible. Any art produced or photomechanically reproduced from this publication for commercial purposes is forbidden without written consent from the publisher, Walter Foster Publishing.

www.walterfoster.com

3 Wrigley, Suite A

Irvine, CA 92618

Digital Edition: 978-1-61058-083-0

Softcover Edition: 978-0-92926-113-3

Table of Contents

Introduction

Perspective is a technique that allows us to represent three-dimensional objects on a flat surface or plane. In art there are a number of ways to use perspective in order to obtain the illusion of depth, including using color and graduated values of black and white and accurately drawing the subject by applying the rules of the geometric system of perspective.

Linear perspective is thought to have evolved from the early architectural drawings of Filippo Brunelleschi and Leone Battista Alberti in Florence, Italy, in the early 1400s. Brunelleschi drew two panels that were pictorial views of Florence in perspective. These panels made an important impact on architecture and fine artunfortunately, the two original panels were lost. Alberti designed some of the most classical buildings of the 15th century. He wrote the very first book on painting, which covered both theory and technique and had a great influence on the Renaissance artists.

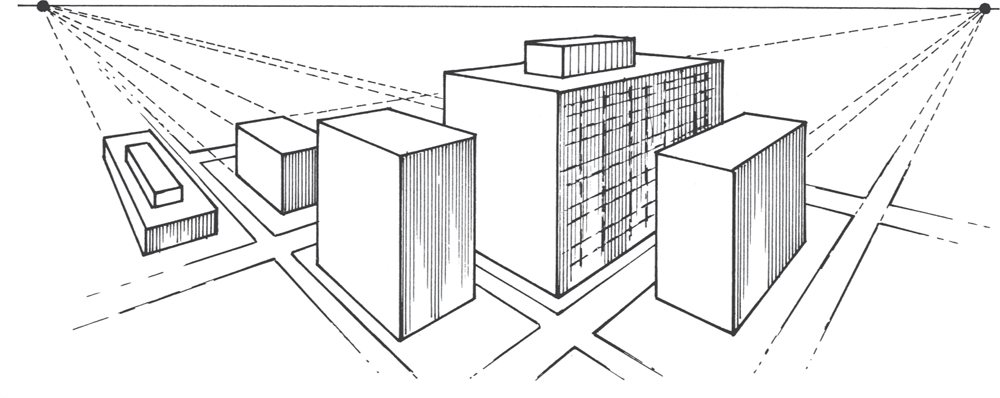

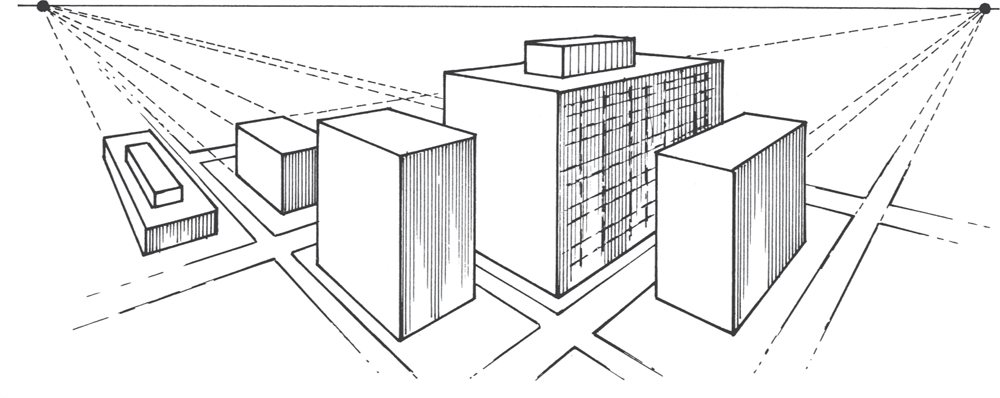

In his book De pictura, Alberti combined the rules and techniques of perspective with the theory that painting is an imitation of reality. Alberti explained how objects appear smaller as they recede, and objects of uniform distance from one another, such as fence posts, appear to merge closer together the farther they recede into the distance. Projected imaginary lines that are parallel to the surface plane converge to one point at the horizonall of the objects in the picture relate to the same horizon. In this theory, all objects can be measured in proper geometric proportion to one another.

Leonardo da Vinci is credited with the general development of the aerial, or atmospheric, perspective. This method is based upon observations that contrasts of color and values of dark and light are much greater in objects that are close than in those that are distant. Atmosphere and light affect the colors of objects in nature. Aerial perspective observes that distance affects the color of objects and that the same color appears cooler and lighter due to a bluish-white affect created by atmosphere when farther in the distance, and warmer, darker, and more intense when closer. Also, lines, edges, and contours are more clearly defined in objects that are closer than in those more distant.

The knowledge of perspective is invaluable to the serious artist. If we know and understand the basic theories of perspective, we can render artwork in any degree of realism or deliberate distortion. In this book I will present the rules of perspective so that you can use them as a guide in the preparation of your work.

I truly hope you will enjoy my step-by-step guidance in this comprehensive study of perspective.

How to Achieve Perspective

In order to achieve perspective, we must make a number of observations. The forms or objects that we draw on a flat surface actually have depth and dimension in real life. As we view them and place their shapes and forms on our drawing surface, we must always try to represent that depth to make the objects appear realistic.

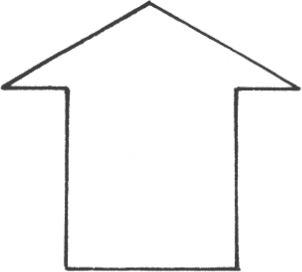

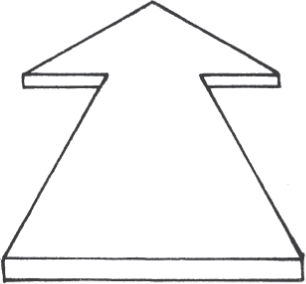

In the examples below, notice that one of the arrows and one of the roads appears to have depth while the others appear flat.

No depth

Depth

No depth

Depth

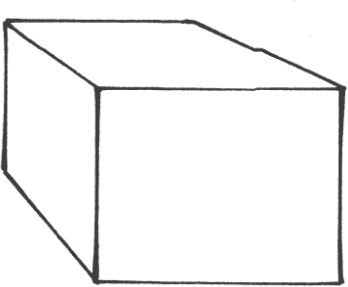

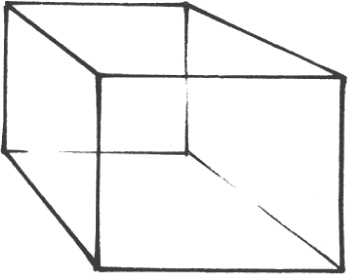

The foundation of all good paintings and drawings is the accuracy of perspective and depth. In order to make the task of obtaining depth and form easier, think about the object you are drawing in its entirety. Do not just look at the front visible surface, but imagine the complete object as the planes of the sides recede. To draw a box, sketch it as if it were transparent. By drawing this way you will not only understand the box better, but are also more likely to draw it correctly and portray the illusion of depth.

Sketch showing visible surfaces

Same object with all planes sketched

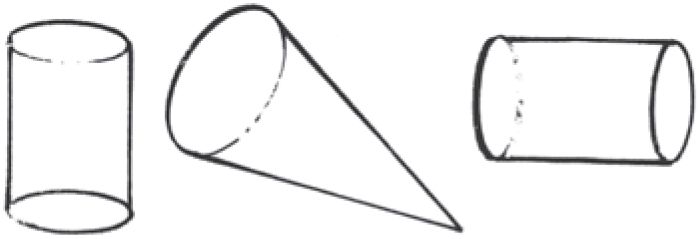

Other examples of depth by transparent sketching

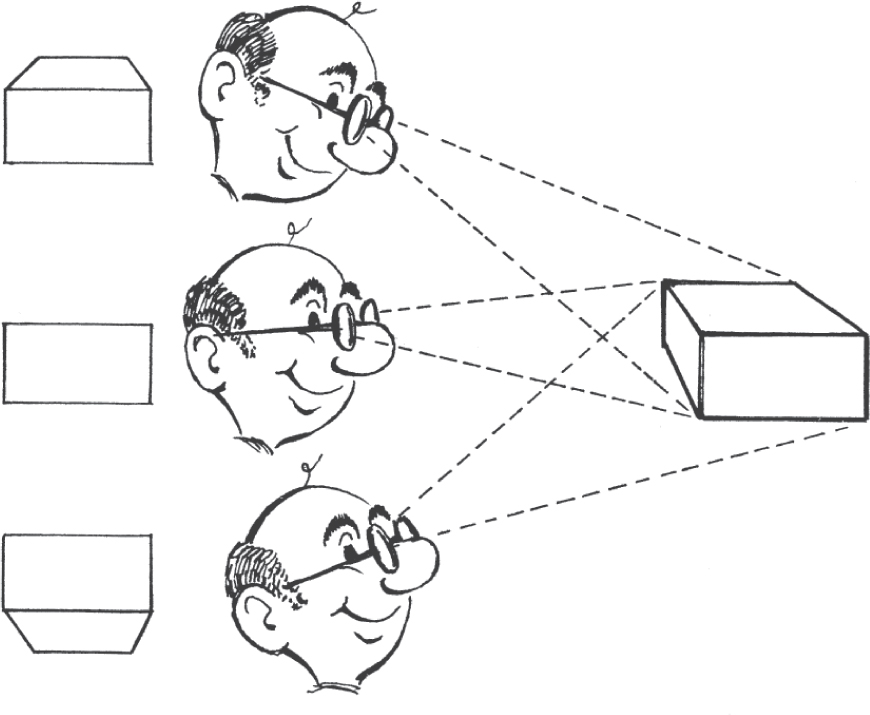

Objects appear differently when viewed from various positions. Because of this, its important to establish the viewing point and stick with it. When observing a subject, we see depth and three dimensions. When we draw this subject onto our flat surface as it appears to the eye, we are then drawing in perspective.

Try to freehand your drawings as much as possible, while still using perspective to check for accuracy or to establish a complex subject. Relying on perspective too much and omitting the freedom of sketching by eye can give your work a stiff, mechanical appearance.

Some helpful tools are a T-square, a triangle, and a compass. You can also find sets of ellipse guides at various degrees of angle, circle guides, ships curves, and so forth. These are expensive though, and unless you are planning to go into mechanical and technical illustration, I suggest sticking with the simple tools: a drawing board, a T-square, a triangle, thumbtacks, and string.