Sean Isaac is a fully certified Alpine Guide with the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides. He has been ice climbing for thirty years and instructing ice and mixed climbing for the past twenty years. During that time, he has taught more than a thousand people the art of moving over frozen waterfalls. Based in Canmore, Alberta, in the Canadian Rockies, Sean was a key member of the modern mixed climbing movement in the late 1990s and early 2000s, establishing classics like Cryophobia, The Asylum, Mixed Monster, Uniform Queen, and The Real Big Drip, to name a few, and repeating testpieces like Musashi (M12). He has competed in the Ice World Cup, Ouray Ice Festival Competition, Bozeman Ice Festival, and Festiglace, with a handful of podium placements. He has traveled all over the world in search of new routesto the remote ranges of Alaska, Patagonia, Peru, Pakistan, and Kyrgyzstan. Sean is also the author of several ice and mixed books including Mixed Climbing in the Canadian Rockies by Rocky Mountain Books, Mixed Climbing by FalconGuides, and Ice Climbing Leader Field Handbook by the Alpine Club of Canada. In addition, he has been the editor of the Canadian Alpine Journal for the past fourteen years. For more information, visit Sean at www.seanisaac.com, IG: @seanisaacguiding, and FB: @seanisaacguiding.

Tim Banfield has been ice climbing for sixteen years and has worked in the climbing photography industry for the past decade, gaining experience in his nicheice climbingwhile at the same time writing feature climbing articles that focus on destinations. Tim has journeyed to Alaska, Nepal, South America, the Alps, and all over Canada pursuing icy and snowy objectives. As a seasoned climbing photographer, he is passionate about capturing authentic ice and mixed climbing images taken in the moment. In addition to writing and photography, he is also involved in real estate. Outside of the office, Tim enjoys climbing, skiing, and taking photos of his dog Trango. For more information, visit Tim at www.timbanfield.com, IG: @timbanfield, and FB: @timbanfieldphotography.

W riting a book is a major project and is in no way just the sole labor of the authors. There were many people involved in this process that we would like to acknowledge and thank. All of these people have helped make How to Ice Climb! the best it can be. We (Tim and Sean) thank you for your words, edits, photos, advice, knowledge, skills, belays, and much more.

Writing contributions: Conrad Anker (foreword), Grant Staham (avalanche), Steve House (training), Nikki Smith (Utah), Brandon Pullan (northern Ontario), Jas Fauteux (Quebec)

Technical advisors: Marc Piche (ACMG), Dale Remsberg (AMGA), Marc Beverly (Beverly Mountain Guides), Kolin Powick (Black Diamond), Grant Statham (Parks Canada)

Extra photos: Jon Glassberg, Austin Schmitz, Sebastian Taborszky, Alex Popov, Alex Ratson, Aaron Beardmore, Tim Emmett, Dane Christensen, Jim Elzinga, Chic Scott

Climbing models: Larry Shui, Tiff Carleton, Jeff Mercier, Maarten van Haeren, Patrick Lindsay, Chris Wright, Aaron Mulkey, Jon Walsh, Alex Pedneault

Proofing: Ian Welsted, Maarten van Haeren, Chris Wright, Raf Andronowski, Jon Jugenheimer, Aaron Mulkey

FalconGuides staff: David Legere, Ellen Urban, Mason Gadd

Equipment: Adam Peters of Petzl, Kolin Powick and Adam Riser of Black Diamond Equipment, Glen Griscom of CAMP, Jeff Perron and Dale Robotham of Edelrid/Sasso

Images: Avalanche Canada, Parks Canada

Studio space: Jeremy Regoto

And many more: Ian McCammon, Quentin Roberts, Paul McSorley, Shaun King, Jordy Shepherd, Zac Bolan, Kat Wood, Zhou Peng, Brent Peters, Manoah Ainuu, Nathalie Fortin, Stas Beskin, Etienne Rancourt, Doug Shepherd, Ryan Vachon, Takeshi Tani, Lindsay Fixmer, Samira Samimi, Erik Wellbourn, John Frieh, Nate Goodwin, Daniel Harro, Pierre Raymond, Barry Blanchard, Jack Tackle, Mark Howell, Marco Delesalle, Steven Campbell, Kris Irwin, Marianne van der Steen, Gord McArthur, Brette Harrington, Pack LHirokoi, and Trango (Tims canine companion)

Nathalie Fortin lost in a sea of ice on Rio del Lobo (WI5, 40 m) in Rivire-du-Loup, Quebec, Canada.

Dynamic Shock Load Evaluation of Ice Screws: A Real-World Look

J. Marc Beverly, BS-EMS, M-PAS

Stephen Attaway, PhD

November 2005

ABSTRACT

Background: It is unknown how many climbers take lead falls on ice screws placed in waterfall ice. Generally, what is reported are accidents that occur when ice screws fail or are pulled from the ice. To date, there is very little information regarding ice screw testing.

Methods: Over the period of eight days of drop testing, we conducted a randomized placement of short ice screws in real-world vertical waterfall ice. Different fall factors, including the UIAA standard, were evaluated to determine what a climber might expect from dynamic shock loading of an ice screw in real climbing conditions.

Results: 61 drops were performed on real world ice on ice screws.

Conclusions: We show that while ice is a variable medium, a predictable and surprisingly strong normogram can be produced in the conditions we performed our testing in. However, because the methods of judging ice conditions are based solely on experience, it may be difficult for novices to discriminate these conditions. The perception that ice screws are weak protection when good ice is utilized is unfounded.

A definition of terms has been created that may help provide a nomenclature for discerning ice conditions.

INTRODUCTION

The main objective was to gain an understanding of the behavior of ice screws under dynamic shock loading and peak forces needed to hold a falling ice climber in a real-world setting. There is little information regarding real-world testing. Rather, most testing is done in laboratories and the tests performed there only evaluate the tensile strength of the materials and not necessarily the application for which they were intended to be used in the first place. Climbers rely on word of mouth, books, periodicals, and training from others to gain insight on the equipment used. Good data are not only hard to find but are difficult to acquire outside in real-world conditions. This was an attempt to find scientific-based data that might help climbers think more critically about their ice screw placements.

HYPOTHESES

Peak forces seen in ice climbing are equivalent to those seen in rock climbing. It is thought that ropes with more stretch decrease shock load and thereby decrease peak forces on an ice screw. Does using a new rope play a role in what peak forces are seen? If so, how?

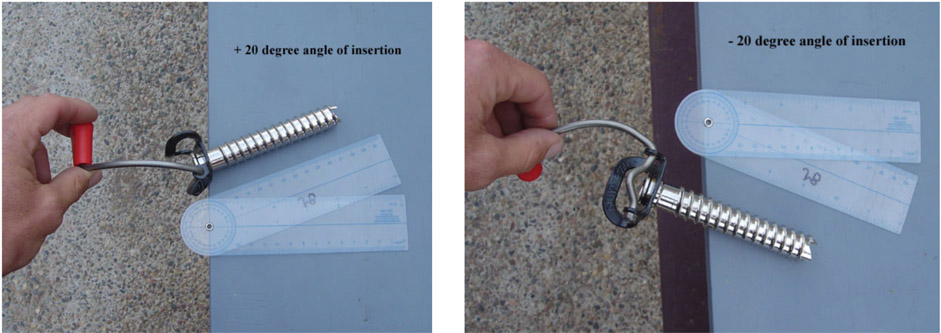

Considering only being able to place the shortest ice screws on the market and using the UIAA test configuration for dynamic mountaineering ropes for lead falls, do peak forces seen in dynamic shock loading of ice screws in the orientation of +10 but +30 hold in fair to good ice?

A large spread of results has been reported on ice screw strengths, and the CE tests ice screws in a nonice medium for approval. The tests that abound are at different forces and time durations. Can drop testing in a natural forum of actual ice climbing produce more realistic and repeatable results?

Figure 1: Defining the angles: left: a positive 20; right: a negative 20. These angles are relative to vertical ice from the horizontal/perpendicular line relative to the ice face