R. G. Collingwood

Robin George Collingwood was born on 22nd February 1889, in Cartmel, England. He was the son of author, artist, and academic, W. G. Collingwood.

Collingwood attended Rugby School before enrolling at University College, Oxford, where he received first class honours for reading Greats. He became a fellow of Pembroke College, Oxford, and remained there for 15 years until he was offered the post of Waynflete Professor of Metaphysical Philosophy at Magdalen College, Oxford. He was greatly influenced by the Italian Idealists Croce, Gentile, and Guido de Ruggiero. Another important influence was his father, a professor of fine art and a student of Ruskin.

Collingwood produced The Principles of Art in 1938, outlining the concept of art as being essentially expressions of emotion. He claimed that it was a necessary function of the human mind and considered it an important collaborative activity. He also published other works of philosophy, such as Speculum Mentis (1924), An Essay on Philosophic Method (1933), An Essay on Metaphysics (1940), and many more. In 1940, he published The First Mate's Log, an account of a sailing trip he undertook with some of his students in the Mediterranean.

Collingwood died at Coniston, Lancashire on January 1943, after a series of debilitating strokes.

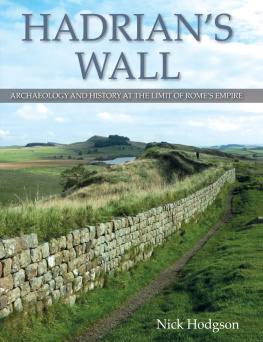

A GUIDE TO THE ROMAN WALL

PART I INTRODUCTION

FOR THREE CENTURIES and more the Roman Wall has been recognised as one of the most remarkable things in the British Isles. It is an object of pilgrimage to travellers from all parts of the world, and the books about it would fill a small library. In the past its visitors have been mostly historians and antiquaries, and it is for their use that previous descriptions of it have generally been designed. But the Wall is now attracting year by year an increasing number of people who, without any claim to being archaeologists, take an interest in monuments of the past; and so happily does it combine imaginative appeal with varied and picturesque scenery that the visitor must be hard to please who does not think his visit well spent. For many of these visitors, Bruces Handbook is too elaborate, and Miss Mothersoles Hadrians Wall, with its charming illustrations, too much of a library book; they want something simpler, cheaper, and more compact, and it is for them that this little guide has been written. Subsequent editions, while retaining the scale of the first, have been extensively corrected so as to include new information; the same process has now been repeated (1955).

ACCESS

To see the Wall you must walk; but you never need walk more than a mile from the point at which you have left your car or bicycle. Newcastle and Carlisle are the starting-points for people arriving by train, whether from north or south; in both it is easy to buy maps and books, and to see museumsthe Black Gate at Newcastle and Tullie House at Carlislecontaining large and interesting collections of inscribed and sculptured stones, pottery, and other relics. But the visitor who does not set out to be an antiquary will put the Wall first and the museums second, to be seen after the Wall itself, if then. The part that is most worth seeing is the section, 25 miles long, lying between Halton and Birdoswald; and of that section the really spectacular part lies between the North Tyne at Chesters and the Tipalt Burn at Thirlwall. Here, and here alone, the actual Wall stands high above ground for miles together; elsewhere the earthworks that accompany it are plain enough, but the Wall itself is seldom visible.

The cyclist or walking tourist who wants to see most in the shortest time will go by train or by bus from Newcastle to Humshaugh, changing at Hexham, or from Carlisle to Gilsland, armed with the Hexham sheet of the one-inch Ordnance map. Let us suppose that he begins at Humshaugh. He will visit the Roman bridge over the North Tyne and the fort of Chesters and follow the main road westward to the top of Limestone Bank, and so past Carrawburgh to Sewingshields, where the Wall follows the heights on the right while the road diverges to the left. Nine miles from Humshaugh, he reaches Housesteads, and here he will see enough to occupy him till it is time to think of his nights lodging. If he has time and energy, it is well worth his while to follow the Wall on foot from Housesteads to Cawfields, for here the scenery and the Wall are both at their best; or, if he is bicycling, to turn aside from the main road once or twice along the branch roads that lead to the right. Next day he can visit the Haltwhistle Burn fort, Great Chesters, the Nine Nicks of Thirlwall, the bridge at Willowford and Birdoswald. These two days will show him all the finest things on the Wall, and if he is bicycling he can compress the two days into one, by omitting some of the places.

If he wants to see more, he may start from Corbridge and see first the Roman supply-base there; and then follow the Roman road, Dere Street, up the hill to the Wall, making a detour eastward to Halton, and finally tracing the Wall westward to the North Tyne. Another day he may work westward from Gilsland to Lanercost, ending at Brampton. This ought to content him, unless he is by now smitten with Wall-fever, in which case he must turn to the second part of this guide and choose for himself. It is worth while to remember, in planning a walk or a bicycle ride, that the Wall lies high and is exposed, and that the prevailing wind is from the west.

The motorist or motor-cyclist, who will not be using the railway, can vary this programme. He will approach the Wall by road, cutting out Newcastle and Carlisle. From the south, he can take Dere Street, the Roman Great North Road, over the Durham moors by Lanchester and Ebchester, and come into the Tyne valley, as the Romans came, at Riding Mill, and so to Corbridge; or from Penrith he may climb the Pennines to Alston and so to Brampton, passing the Roman fort of Whitley Castle with its elaborate ditch-system. Both roads provide splendid scenery; the view westwards from the summit between Penrith and Alston is the finest in England on a clear day. If he comes from the north, the Romans are again his guides on the east, where he will cross Carter Bar and follow Dere Street southward, past the forts at High Rochester and Risingham, to Corbridge or Hexham or Chollerford; on the west he will approach Brampton by way of Longtown on the Esk. These four are the best roads for the Wall; all are good roads, and the first three in particular run through fine scenery.

The Newcastle-Carlisle road, called by Newcastle people the West Turnpike, and sometimes inaccurately known as Wades Road, after General Wade who did not build it, is a very fair motor road, which makes it easy to get by car to within a mile or less of any point on the central portion of the Wall. But to facilitate its construction, just after the Forty-Five, when Wade at Newcastle could not get his guns across to Carlisle to stop Prince Charlie, the Wall itself was destroyed almost the whole way from Newcastle to the North Tyne, and the road built on its foundations. The West Turnpike is therefore a mixed blessing to Wall-lovers; but it has this advantage, that motor camping and caravanning can nowhere be better done than on the Wall.