Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

YALE UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS IN ANTHROPOLOGY

NUMBER 15NOTES ON HOPI ECONOMIC LIFE

BY

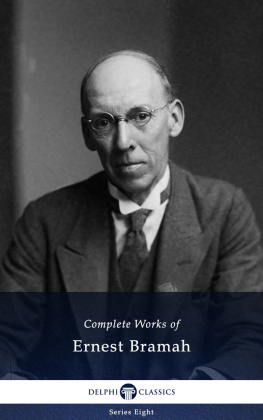

ERNEST BEAGLEHOLE

FOREWORD

The following notes represent a study of certain aspects of the culture of the two Second Mesa Hopi villages of Mishongnovi and Shipaulovi. Fieldwork was done in the summers of 1932 and 1934. My principal informants were Sakmasa and Roy of Mishongnovi, and Yusiima of Shipaulovi.

My obligations are many: to the Commonwealth Fund and the Bureau of Indian Affairs for making possible the fieldwork; to Yale University for the grant of a Sterling Fellowship which enabled me to write the manuscript; to Dr. E. C. Parsons for reading the first draft of the manuscript and for her kindness in allowing me to consult the proof of Stephens Hopi Journal; to my informants for their co-operation which alone made the fieldwork fruitful; to Dr. Edward Sapir for introducing me to American anthropology and for the stimulus of his teaching and friendship; finally, to Pearl Beaglehole for her generous and constant help both in the collection of field material and in the preparation of the manuscript. I have to thank her also for the chapter on Foods and Their Preparation, included in this monograph.

ERNEST BEAGLEHOLE

HOUSEHOLD, KIN AND CLAN

BEFORE I take up in detail the study of Hopi economic processes and values, it is necessary to summarize the main facts about the organization of Hopi household, kin and clan units, and to characterize in a preliminary fashion the economic aspects of these basic social institutions.

The household consists essentially of the father, the mother, and one or more children. Since Hopi marriage is matrilocal, there will usually be included in the household group unmarried or widowed brothers and sisters of the wife, married daughters, their husbands and children, and also widowed or divorced sons. {1} This enlarged family group occupies one house block, consisting of one or more living rooms and storerooms. Occasionally married daughters occupy adjoining house blocks, or other houses owned by the maternal family elsewhere in the village.

Whatever its composition, however, the household group remains the fundamental unit in social and economic affairs. Dr. Parsons has coined the phrase brittle monogamy to characterize Hopi marital arrangements. Although divorce is a simple matter and monogamous relations are theoretically subject to a certain amount of change, it is not correct to conclude that short-lived monogamy is the rule among the Hopi, or that the household group is marked by neither stability nor permanence. {2} Various patterns help to even the balance in such a manner that the family group may be looked upon as a relatively stable social unit. Father and mother co-operate in the task of bringing up the children, and the children in return develop sentiments of affection and respect for both parents. The rle of the maternal uncle will vary according to the set-up of the household. It is usually his duty to instruct his sisters son in ceremonial and ritual; he is called upon later to advise on marriage arrangements and to help provide the wedding outfit for the bride of his sisters son. He takes over the duties of the father in other spheres only if the mother is widowed and does not remarry, or if the mother dies and the father returns to his own maternal household, leaving his children in the household of his dead wife.

The reciprocal ties of dependence and group unity which mark the household in the social sphere are carried over into economic activities. Here the household acts as the ultimate unit of production and consumption. In marriage both partners assume definite obligations to contribute to the economic welfare of the household; when the family is enlarged by the presence of maternal relatives all are brought within the economic partnership. The division of labor between members of the group and the tasks to which all apply themselves in order to produce the household wealth are analyzed in a later section. The household is also the unit of consumption for this wealth, and, apart from feasts or ceremonial occasions when the men are required to eat in the kiva, the household and its guests eat all meals in common in the maternal house.

That the economic obligations binding together members of the household are considered very real and definite by the Hopi is demonstrated by an analysis of the causes of some of the household quarrels that came to my attention. Temperamental or personality differences often seemed to be fundamental; but in some of them the immediate cause of the friction lay in the charge that one or another member of the household was not fulfilling the economic duties that his or her status in the household demanded. Where conflict had not become acute peace was usually restored to the harassed household only by the offenders mending his ways and co-operating more fully, or else by his moving to the house of another relative. The point to be emphasized is that membership in the household means the fulfilling of definite social and economic obligations which must be conscientiously observed if all are to participate in the economic goods of the community.

THE BILATERAL KIN GROUP

Marriage among the Hopi not only links together husband and wife in a more or less durable bond; it also serves to connect two groups of kindred belonging to different clan affiliations. In this new kin grouping brought about by marriage the paternal relatives unite with those of the maternal family in the education of the child, and both together act as a closely co-ordinated unit in many economic activities.

The Hopi kinship system is classificatory, of the Crow type, and bifurcates linked kindred according to their paternal or maternal connections. Thus the Hopi use the term inaa to designate (my) father, fathers brother, fathers sisters son and fathers clansmen generally; iDaha for (my) mothers brother or other clansmen of her generation; ia for (my) mother, mothers sister or step-mother, and i i aa for (my) fathers sister or fathers sisters daughter (plural i i a a Da). The term isoo is applied to both paternal and maternal grandmothers, usually also to the fathers eldest sister; iwaa is used for both maternal and paternal grandfathers. {3}

A brief review, to be amplified later, of the personal life of the individual from birth to death will serve to bring into focus the obligations and duties of both groups of kindred towards the child, their co-operation at life crises, and the reverse obligations of the child in terms of his bilateral kinship affiliations.